Insight Focus

Brazil announced measures to curb rising food prices in March. This includes a removal of the import duties on corn and soybean products for non-MERCOSUR countries. However, the efforts are unlikely to make much impact given that the bulk of Brazil’s grains import trade is with MERCOSUR partners.

As food prices rise in Brazil, the government has been looking at options to rein them in. The rises have been driven primarily by climatic factors and exchange rate volatility.

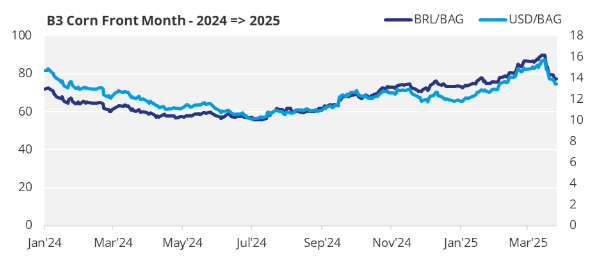

Corn prices, for example, began strengthening late last year, fuelled by the Brazilian real’s devaluation against the dollar. Further support came from delays in fieldwork, including soybean planting and harvesting, which in turn disrupted the Safrinha corn crop calendar.

Source: B3/ Valor Econômico

Import Tariffs Removed

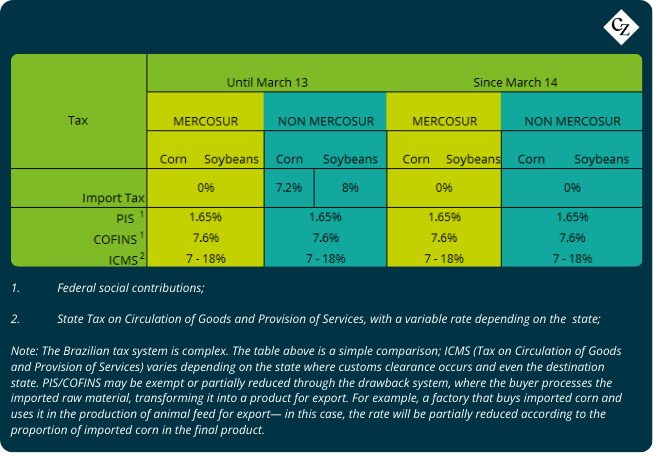

On March 13, the Brazilian government announced a series of measures to curb the rise in food prices, including an exemption from tax on the import of corn, soybeans, soybean meal and soybean oil.

In addition to being among the world’s largest suppliers of corn and soybeans, Brazil’s participation in MERCOSUR already exempts imports of these products from its main clients, Paraguay and Argentina. But does the exemption for other countries make any difference?

In short, probably not. Prices for the B3 corn front month already began to retreat after peaking at BRL 89.90/bag (USD 15.75) on March 17, a movement much more related to the positive outlook for the Safrinha than any political attempt to reduce prices “by decree”.

The decree immediately suspended the import duty, which was 7.2% and 8% for corn and soybeans, respectively; between 6% and 10% for soybean meal, depending on the classification; and 10% for soybean oil.

As a result, any country now has the same commercial advantages as MERCOSUR members—a bloc that promotes the free flow of goods and services between Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay, and, as of 2024, Bolivia.

Previous Implementation

The measure had previously been implemented from October 2020 to January 2021 for soybeans and until March 2021 for corn, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which reached Brazil in February 2020. It was later extended for both commodities until December 31, 2021.

The extension occurred primarily due to the occurrence of frosts during the critical period of the Safrinha corn crop (second crop), which caused a reduction in Brazil’s corn production.

The first estimate by CONAB in October 2020 forecasted 105.17 million tonnes, but the final projection was revised to 87 million tonnes, representing a 17.3% drop from the initial forecast and a 15.1% decrease compared to the 2019/2020 crop, which had been 102.6 million tonnes.

This caused concern in Brazil over supply of critical grains and prompted the import taxes to be dropped temporarily.

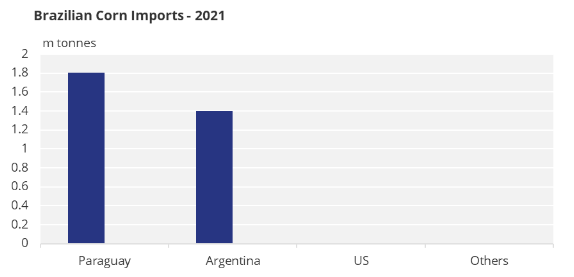

The result was Brazil’s highest volume of corn imports since data collection began in 1997, totalling 3.2 million tonnes. Of this, 99.6% came from the Mercosur free trade area, primarily from Paraguay (1.8 million tonnes, 56.37%), followed by Argentina (1.4 million tonnes, 43.6%). Imports from outside the bloc were minimal, with just 1,005 tonnes (0.4%) coming from the US.

These imports represented 4.34% of Brazil’s domestic corn consumption for the season, which totalled 71 million tonnes. As expected, the measure adopted in late 2020 failed to curb rising corn prices, which climbed from BRL 66.45/60 kg bag (USD 11.77) in early October 2020 to a peak of nearly BRL 110/60 kg bag (USD 20) by the end of April 2021.

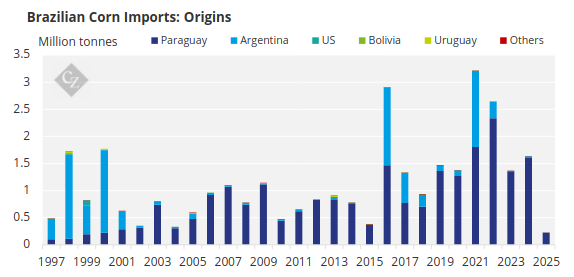

As one of the largest global suppliers, Brazil has imported only 32.5 million tonnes of corn since 1997 — with 99% coming from Mercosur, primarily from Paraguay (23.3 million tonnes), followed by Argentina (8.9 million tonnes), and thirdly, the US, with only 172,500 tonnes.

Efforts to remove tariffs appear to have had little effect because Brazil’s main suppliers already benefit from permanent tariff exemptions due to the free trade agreement.

Source: COMEXSTAT

Will the Outcome Be Different This Time?

Some things have changed since that season. In addition to a substantial increase in production, there has been significant progress in the infrastructure for transporting and receiving goods from the northern ports of the country, in the so-called Arco Norte.

This now allows imported corn from the US to reach the North and Northeast regions at more competitive prices than back then. However, even if the import parity is favourable at some point, it’s important to consider that not all US genetically modified strains are accepted in Brazil. Furthermore, Brazilian protocols impose strict labelling and traceability requirements for GMO products, adding significant bureaucracy and high costs to the process.

Just like five years ago, the exemptions are likely to generate more repercussion than practical impact. In mid-March, rumours emerged about a small quantity of corn imported from the US heading to the state of Bahia; however, by the end of the month, this transaction had not yet been confirmed.

Furthermore, by the third week of March, according to the Foreign Trade Secretariat (SECEX), only 110.5 tonnes of corn and 10 tonnes of soybeans had entered through Brazilian ports.

Government Intervention Fails to Control Commodities

Once again, agricultural commodities remain agricultural commodities, independent of any government’s will and, as always, reflecting the purest dynamics of supply and demand laws. No capitalist government in the world can control the prices of a commodity without paying a high price.

A clear example of this is the Argentine export taxes (“retenciones”), widely implemented in the 2000s, when the government imposed high rates on the country’s exports – reaching 35% for soybeans and 20% for corn, leading to significant economic losses from which Argentina is still trying to recover.

Thus, the Brazilian government must seek other ways within the supply chain to reduce medium- to long-term costs, such as improving logistical efficiency or implementing internal tax reforms. In the short term, a record soybean crop, along with the strong progress of the Safrinha corn crop—if it continues as expected—should help alleviate prices.