Opinions Focus

- Brazilian corn exports set a new record in Aug 2022, with 7.5m tonnes shipped

- With the “safrinha” harvest nearly complete, a slight increase in prices was enough to make farmers sell

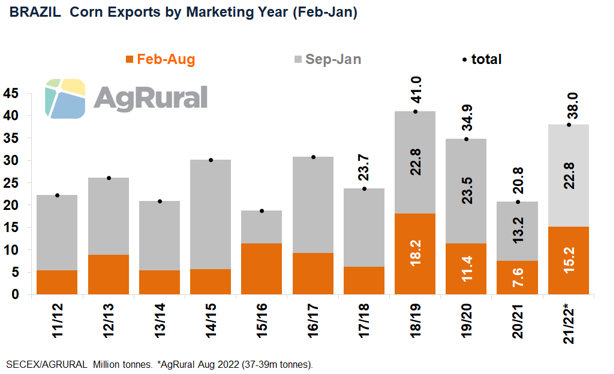

- Despite ample supplies, Brazil’s 21-22 exports may not surpass the record 41m tonnes set in 2018-19

Dashboards that may be of interest…

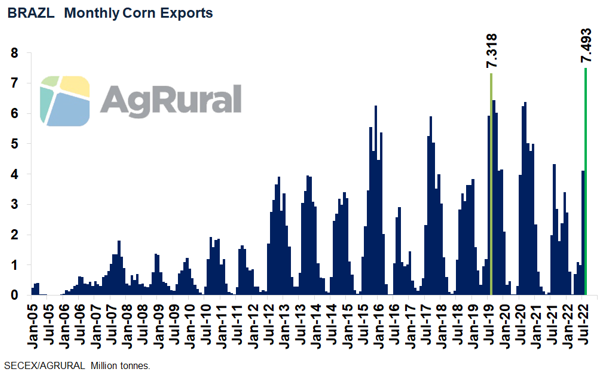

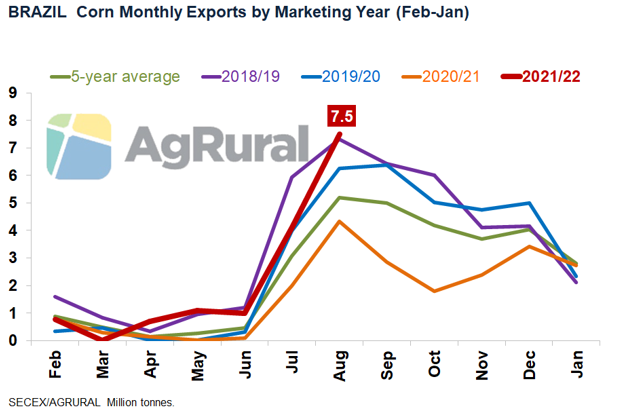

With the 2022 second corn crop (“safrinha”) harvest at its final stretch and soybean shipments losing steam, as is usual at this time of the year in Brazil, corn exports took the spotlight in August. Brazilian ports shipped 7.493m tonnes during the month, a new all-time high for the country, surpassing the 7.318m exported in Aug 2019.

No surprise there, as August is normally the strongest month of the year for Brazilian corn exports. In a year of a huge production, greater demand from the European Union, which is facing a harsh crop failure, and difficulties in Ukraine (which, even with the resumption of shipments through Black Sea ports, has not yet been able to export the usual monthly volumes), Aug 2022 was destined to leave its mark on the history of Brazilian corn exports.

Farmer Selling Takes Off, But Still Lags

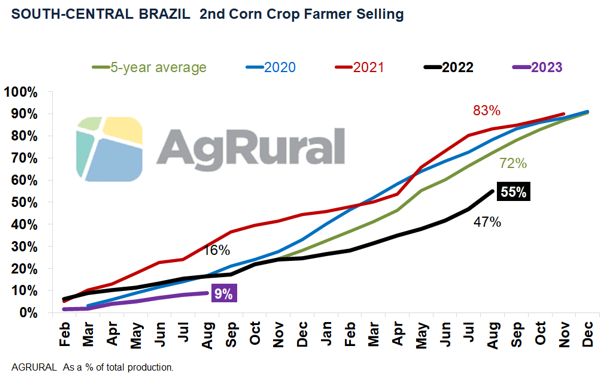

A real surprise in Aug 2022 was the farmer selling progress. AgRural data show that the month ended with 55% of the 2022 “safrinha” production sold in south-central Brazil, with an increase of eight points from late July and the best performance of the season so far.

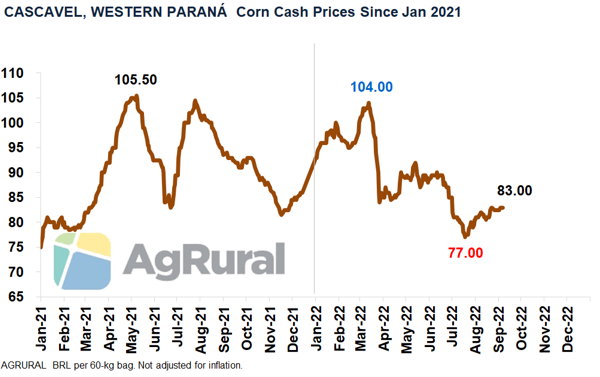

Higher quotes in Chicago, driven by the prospect of lower production in the US, and the weakness of the Brazilian Real against the US dollar made Brazilian prices move away from the year’s lows, made in July, and favoured several trades across the country, especially in the second half of the month.

The lack of storage room and payment deadlines also contributed to giving the selling pace a boost in August. Even so, the 2022 “safrinha” farmer selling still lags compared to the 83% of a year ago and the 72% of the five-year average. Almost 37m tonnes of corn are still to be sold by producers, versus 9m a year ago, when productionwas much smaller and the selling pace faster.

Forward sales of the 2023 “safrinha”, on the other hand, remained slow in August and advanced less thanone point during the month, to 9% of the potential production of south-central Brazil, compared to 16% in the same period last year. With much higher production costs, farmers continue to wait for better pricing opportunities to sell a bigger chunk of their next crop.

More Then 40m Tonnes?

Despite the new all-time high made in August and the large volume suggested by the vessel line-up for September, Brazil’s 2021-22 corn exports are not likely to surpass the record 41m tonnes set in 2018-19. Although there is more than enough corn to boost exports, producers are not inclined to continue selling volumes as large as those sold in August – unless prices improve further.

Last week, Brazil’s federal crop agency Conab reduced its export estimate for the 2021-22 marketing year (shipments from Feb 2022 to Jan 2023) by 500k tonnes, to 37m. AgRural, for its turn, sees exports between 37m to 39m tonnes. Although Ukrainian exports are still far from reaching their normal, Brazil faces fierce competition from Argentina, which continues to ship at a very strong pace, and from the US, whose harvest is still good, despite losses caused by heat and irregular rains over the past couple of months.

Is it possible that Brazil exports more than that? Yes, it is. With total production between 113 and 116m tonnes in the 2021-22 crop (depending on the source of the estimate), the country could export 40m tonnes and still end the season with stocks between 6m and 9m tonnes, a decent level in historical terms, especially if the 2022-23 first crop, which is being planted and will start entering the market from Jan 2023, does not face weather problems.

But for exports to reach the mark of 40m tonnes (or more), it will be necessary for China to import a significant volume from Brazil in 2022 (which we consider unlikely); for prices to stop rising in Chicago (avoiding further consumption rationing around the world); and that the Brazilian Real weakens, making prices in the local currency more attractive and encouraging producers to sell the large volume they are still holding on.