Insight Focus

It’s touted as a fuel of the future, but how clean is hydrogen? There’s a huge spectrum of production processes ranging from green hydrogen with low emissions to coal-based methods that are carbon-intensive. The challenge is producing hydrogen with a minimal carbon footprint.

We now recognise that hydrogen, in its molecular form (H2), is valuable both in processing jet fuel, including SAF, and as a potential aviation fuel in its own right. Not in the Apollo sense of powering a rocket, but as a replacement for jet fuel in an airliner. Thus, hydrogen serves as a lever in achieving decarbonisation at both the production and combustion stages. But how do we obtain hydrogen, and at what carbon cost?

The Hydrogen Spectrum

Hydrogen is the most common chemical element in the known universe (the third most abundant on Earth), yet it is not available in its useful elemental (molecular) form due to its reactivity. Even when obtained, it is highly mobile and easily escapes containment. Therefore, hydrogen must be produced and stored, and this is where its carbon intensity and “colour” come into play.

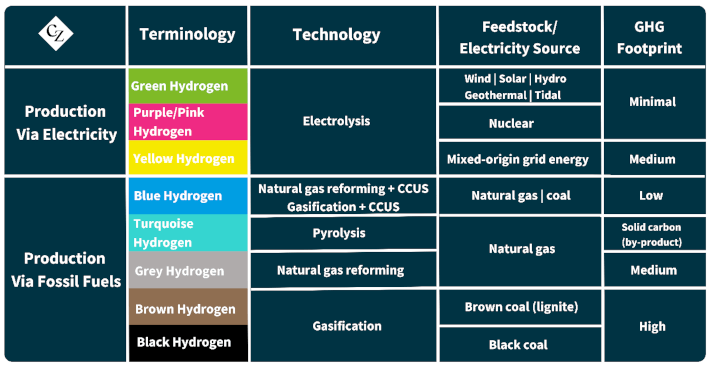

Overall, if the hydrogen production process bypasses carbon altogether, its GHG footprint is minimal; however, if it starts with coal, it becomes highly carbon intensive. From good to bad, this is where the colours come in. Green signifies a negligible carbon footprint, while black indicates a massive one, with a host of colours in between.

The hydrogen spectrum above isn’t just decorative; it’s also informative, with the shift from green to blue, grey, and black representing a decline in desirability – but usually a reduction in cost.

Everyone wants green hydrogen, as it is produced through the electrolysis of water using renewable electricity—a near-perfect process with a near-perfect feedstock. The downside, however, is the limited supply. As we’ve seen before with the slow production of SAF, scaling up is often delayed, and when hydrogen is produced, there are competing uses for it, such as in steel production.

Environmentally speaking, the next best thing to green is blue hydrogen, produced through the steam reforming of methane. This is an age-old process that generates CO₂ as a byproduct, which is a disadvantage. However, to earn the blue badge, the carbon dioxide is captured and either used or stored. Globally, utilization is limited, and storage is even more so, at least for the time being, making the carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) badge more of a chimera in the short term.

Grey has the same provenance as blue but lacks the CCUS, making it poorer in terms of carbon intensity reduction.

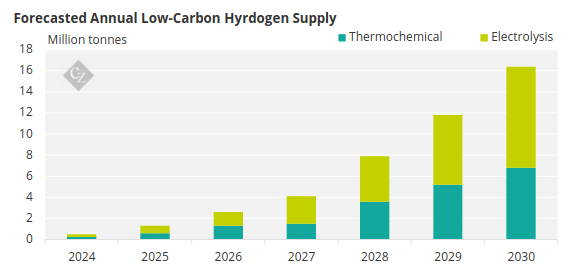

Source: BloombergNEF

Finally, we come to the classic route to hydrogen – steam reforming of coal. This is the process of yore, from which town gas was produced — a less-than-lovely mix of hydrogen and carbon monoxide, one of the most explosive gases and the other one of the most poisonous. Not exactly what you want pumped into your kitchen and oven.

For coal-producing countries over a century ago, it was a great process to produce a useful and valuable gas for domestic and industrial use, street lighting and so forth. However, it’s not a good route when the goal is to reduce carbon dioxide emissions.

And therein lies the paradox – the greater the pathway to hydrogen in order to reduce carbon, say to produce SAF, the more carbon is produced. Back to the drawing board…

Next time, we’ll look at SAF blending – where it’s being implemented, when it might become more common, and how the blending process works.