Insight Focus

Leaders at COP29 adopted new standards for carbon project methodologies. This decision should enable project approval under the Paris Agreement, with the first credits expected by 2025. However, nations remain far apart on the new climate finance goal.

UN Adopts Carbon Standards

The United Nations’ annual climate summit kicked off last week with a key win for the carbon markets, after delegates from more than 190 countries voted to adopt standards that will guide methodologies for carbon-reducing projects. This decision may kick off a wave of investment around the world.

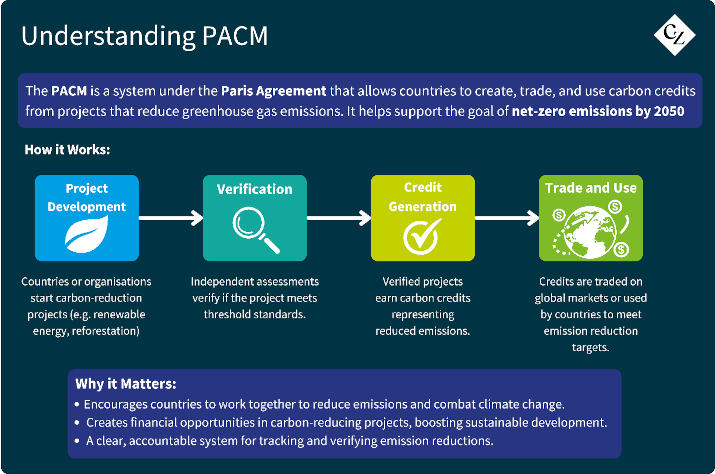

Earlier in the year, the 12-member UN panel overseeing the Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism (PACM), established under Article 6.4 of the Paris Agreement, approved a set of threshold standards. These standards must be met by all methodologies used to calculate carbon reductions from projects like biogas capture or reforestation for them to qualify as official PACM standards.

The UN adoption took place during the opening plenary meeting of the supreme body overseeing the Paris Agreement and triggered a storm of protest from environmental groups and activists, who claimed the rules were agreed upon without any discussion or transparency.

However, the adoption was the final step in a process that has taken more than two years, including a breakdown in talks at last year’s COP in Dubai. Market advocates were keen to emphasize that the panel responsible for developing market standards had conducted extensive consultations.

The early approval of these standards allowed countries to move on to other technical elements of their work on the PACM, which includes developing a registry to record the issuance and retirement of credits, and legal rules around host country authorisation of credits.

Carbon market experts say the adoption of standards to govern methodologies means that the PACM’s administrators can now start to register projects in the new market, as well as transition projects that were initially approved by the Kyoto Protocol’s Clean Development Mechanism into the new market. The first Paris Agreement carbon credits could even be issued by late 2025, they say.

Climate Finance Negotiations Stall

Meanwhile, the mainstream elements of the COP negotiations on climate finance have remained stuck amid disagreements over which countries should be providing funding, and how much.

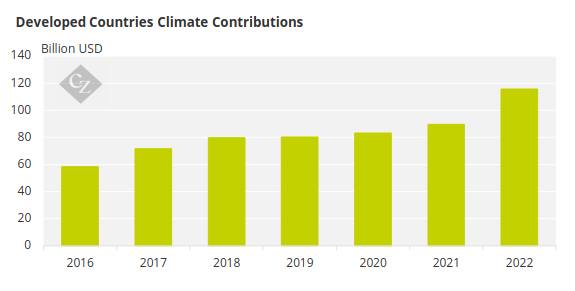

The finance talks are a renewal of the 2009 Copenhagen Accord, in which developed countries pledged to provide USD 100 billion a year in funding to help developing countries deal with the impacts of climate change and undertake their own efforts to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

Source: OECD

This year’s talks for a “New Collective Quantified Goal” on finance have seen some countries propose that developed countries should provide as much as USD 1.3 trillion a year. For their part, developed nations are arguing that they cannot raise that much in public funds and that private finance should also be mobilised to fill some of the gaps.

Rich countries are also pointing the finger at emerging economies such as China and Saudi Arabia, arguing that they are wealthy enough to no longer be considered developing nations and that the UN definitions of developed and developing countries, first set out in 1993, are outdated.

For its part, China has rejected the suggestion that it join the list of developed countries, but it has offered to provide funding to developing countries as part of what it calls “South-South cooperation”.

Nations Prepare Updated Pledges

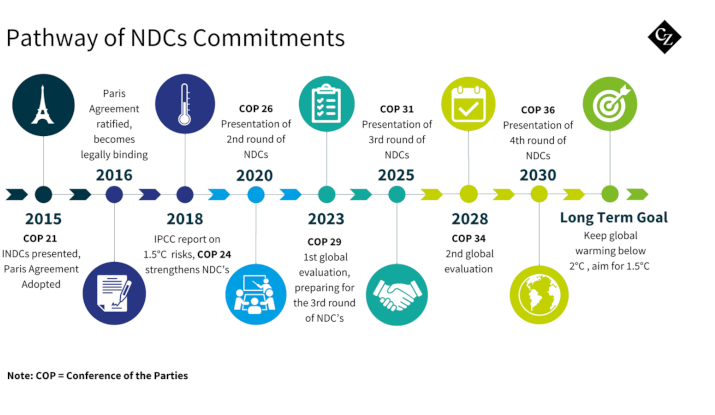

Countries are also setting the scene for updated national climate pledges to be submitted to the UN by February next year. The new round of Nationally Determined Contributions is needed to show all nations’ climate pledges for the period ending 2035. This will allow a calculation of how the Paris Agreement is progressing towards its goal of net zero emissions by 2050.

Speaking in the opening week’s High-Level segment, UK prime minister Keir Starmer announced the country would target an 81% cut in greenhouse gas emissions from 1990 levels by 2035, while Brazil set a goal of 59%-67% reductions by the same time.

The country’s climate change minister said, “our focus is on having an absolute figure that goes from more than 2 billion tonnes/year to 850 million tonnes/year of CO2.”