Insight Focus

- European farmers have taken to the streets in protest over a series of agricultural policy issues.

- One of the biggest issues is decarbonisation, which places great financial pressure on farmers.

- While decarbonisation is necessary, the farmers shouldn’t bear all the costs.

Farmers Take to the Streets

Over the past few weeks, farmers have been staging an almighty protest across Europe’s major cities. Across Germany, France, Spain, Poland, Portugal and more, farmers have been driving tractors into city centres, staging roadblocks with hay bales and manure and clashing with police.

Source: iStock

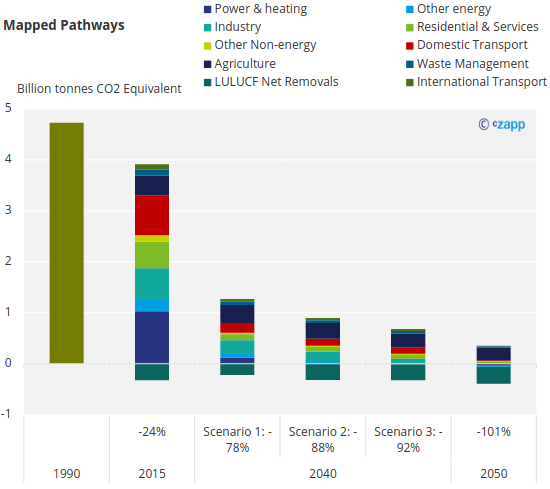

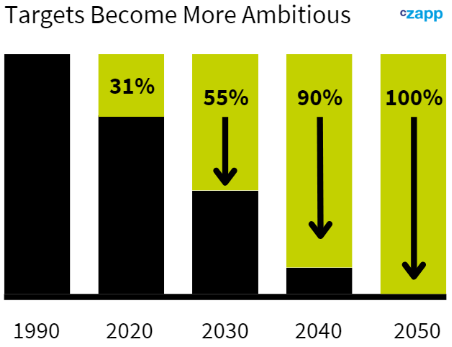

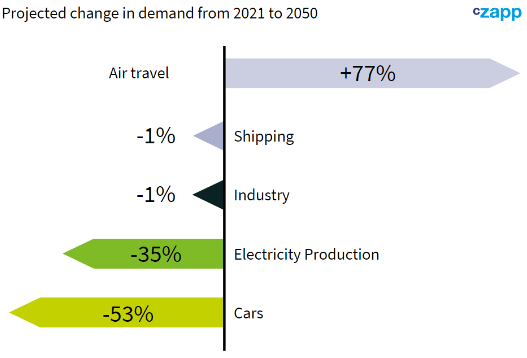

These farmers are protesting a series of issues, but the concerns have been brought to a head by the latest EU legislation on the environment. The long-awaited climate target plan, released last week, provides a roadmap of the EU’s path to emissions reductions by 2040.

The plan was largely expected to target the agricultural sector, among other big polluters. However, after the protests began to spread across the bloc, the European Commission made a swift U-turn. The published proposal largely omitted a plan for emissions reduction across agriculture, instead relying heavily on carbon capture plans to meet emissions reduction targets.

Note: Negative values represent carbon removals

Source: European Commission

Issues Bubble to the Surface

A few years ago, the European Commission (EC) launched the Farm to Fork strategy under the European Green Deal. The European Green Deal was a plan designed to help the EU meet its pledge of reducing greenhouse gases by 55% by 2030, compared with 1990 levels. This can be seen as the previous iteration of the Green New Deal.

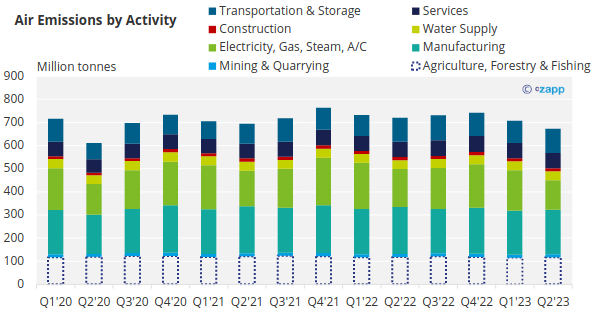

The point of the strategy was to make farming in the EU more sustainable, especially since agriculture is a major carbon emitter.

Source: Eurostat

The plan was extremely ambitious – the EC wanted to ensure that organic practices were used permanently on 25% of land, protect 30% of all farmland, and reduce the use of antibiotics by 50%, pesticides by 50% and fertilisers by 20%.

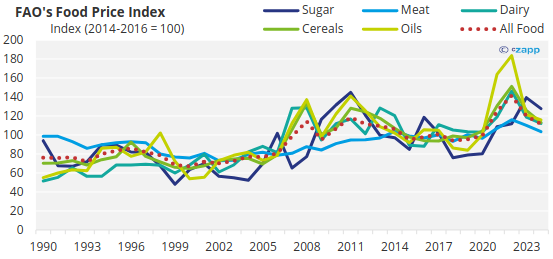

While this was a positive idea in theory, the execution hasn’t been perfect. Farmers – not only in Europe — have been contending with the rising cost of inputs coupled with stagnating food prices over the past few years.

Source: FAO

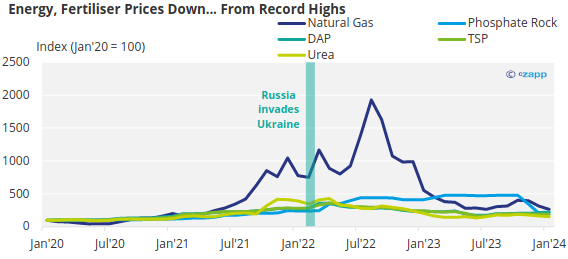

According to the FAO, food prices have risen by just 11% since the 2014-2016 period. Meanwhile, the cost of energy and fertilisers have risen much more rapidly, especially since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

In addition to this price pressure, European farmers have had to bear much of the cost of meeting the requirements of the Farm to Fork strategy. Now, with the threat of a new, more ambitious climate strategy hanging over their heads, farmers downed tools and headed to the cities.

Subsidy Cuts Squeeze Farmers

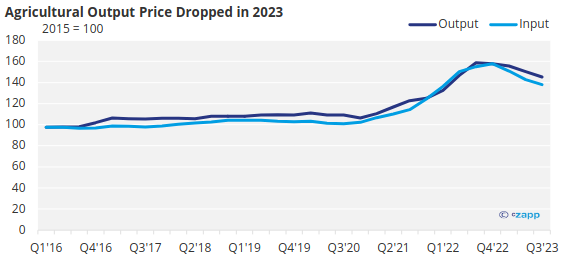

Farmer margins are increasingly squeezed. According to Eurostat data, the price of farm outputs has historically barely outpaced the growth in the cost of inputs.

Source: Eurostat

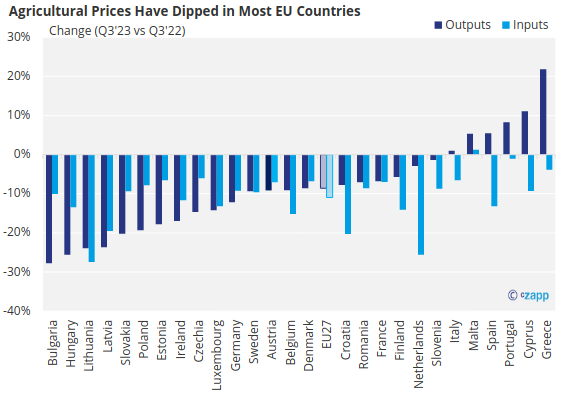

Across most EU countries, the price of agricultural production has dropped in the year between the third quarter of 2022 and the same period of 2023. And while in the third quarter of 2023, input prices largely dropped year over year, this came from a very high level.

Source: Eurostat

After the Russian invasion of Ukraine, energy and fertiliser prices surged and prices have still not fully returned to pre-war levels.

Source: World Bank

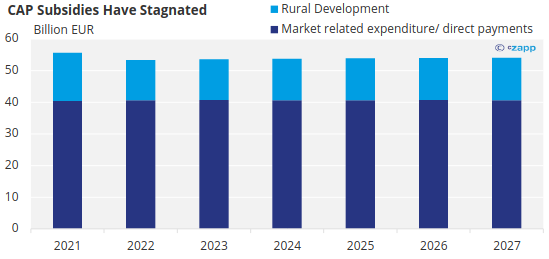

At the same time, CAP payments – the subsidies farmers receive from the European Commission – have stagnated. The budget shows that payments will remain stable to 2027 despite these rising costs.

Source: Europa.eu

Farmers Flag Cheap Food Imports

One of the biggest concerns of the farmers protesting across Europe is the imports coming from countries that are not restricted by the same environmental rules as European farmers. As a result, even imported food can be cheaper than EU-grown produce.

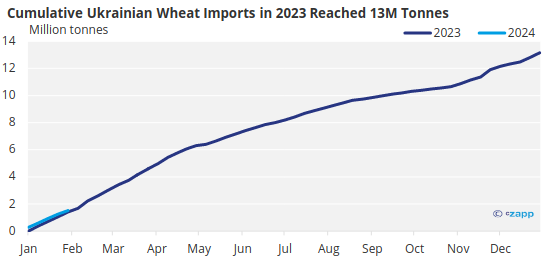

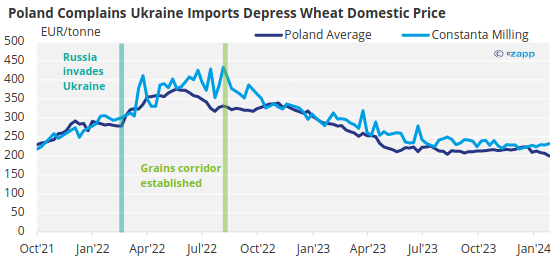

And due to the war in Ukraine and the disintegration of the Black Sea Grains Agreement, a huge number of grains are entering Europe from Ukraine via Poland and Romania.

Source: European Commission

One complaint of Polish farmers is that this is creating a price distortion in European wheat prices. Polish farmers argue that the large volumes of wheat imported from Ukraine are depressing prices that can be obtained by Polish farmers.

Source: European Commission

With falling farm incomes, higher debt levels and pressed margins, it is no surprise that farmers are struggling to fund these decarbonisation efforts being promoted by the central government.

Agriculture Sector Faces Structural Issues

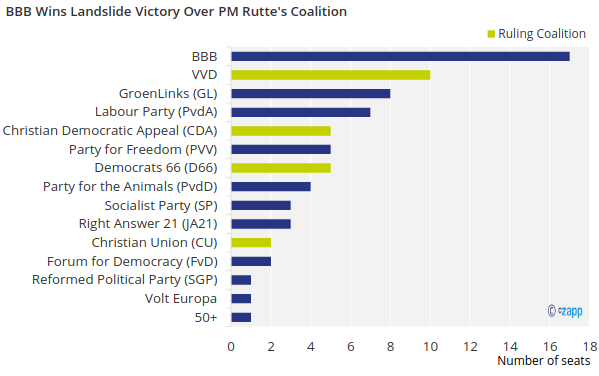

The current situation is reminiscent of a successful protest last year by Dutch farmers, who pushed back on government emissions targets in The Netherlands. These targets would halve nitrogen emissions by 2030 – which would put the meat sector in the crossfire.

The government planned to reduce livestock numbers by a third but its attempts to implement the policy were dashed after major losses in the provincial elections. The Farmer Citizen Movement – known as BBB – made big gains, while Mark Rutte’s ruling coalition parties lost 10 seats.

Source: NOS

While agriculture accounts for only 1.4% of Europe’s GDP, it plays a key role in food security, which is one reason why it holds such power.

But on the other hand, when it comes to food prices and margins, farmers are relatively powerless to market forces. In other words – if consumers are unwilling to pay higher prices, the supply chain and government will be reluctant to pass them on. This means that, more often than not, farmers are the ones to shoulder additional costs.

As it stands, agriculture is one of the biggest carbon emitters and in general, it has been relatively unsuccessful in reducing emissions.

We all agree that something needs to be done about emissions, so what is the long-term solution? Unfortunately, it seems to be a very unpopular one. In the long term, one of the only ways to fund decarbonisation is for farmers to pass on the costs – which would mean a rise in food prices.

This is of course if Europe wants to retain a domestic agriculture industry rather than relying on imports. And this in itself will become a problem if the scope of the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism expands to agriculture.

Another good way to decarbonise – although it would require investment – is for the industry and public sector to embrace new and emerging food technologies. These could include seed technology, farming practices, use of robots or precision mapping to allow farmers to increase yields with the resources they have.

But ultimately, decarbonisation comes at a premium and now, it looks like someone needs to put their hand in their pocket.