- Toll (re-export) sugar refinery profitability is under pressure.

- High dry bulk freight costs make their raw sugar feedstocks more expensive.

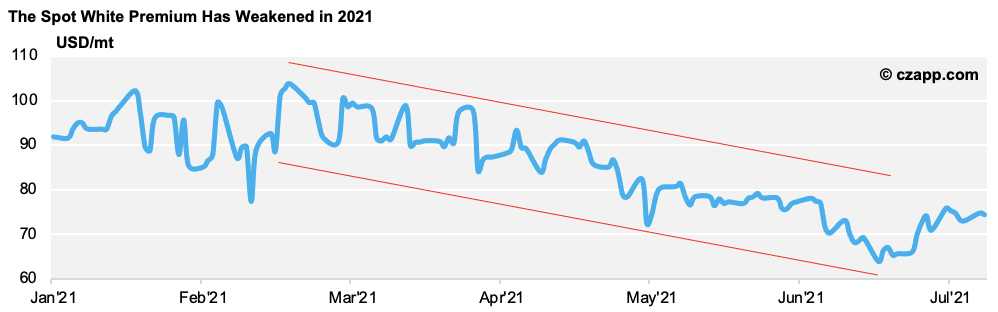

- The white sugar futures market is weak relative to raws.

The Problem for Sugar Refiners

- 2021 is becoming a year to forget for some toll refiners.

- The white premium has been falling all year; it’s the difference between the refined sugar futures and raw sugar futures, so can be used as a crude assessment of toll refiner profitability.

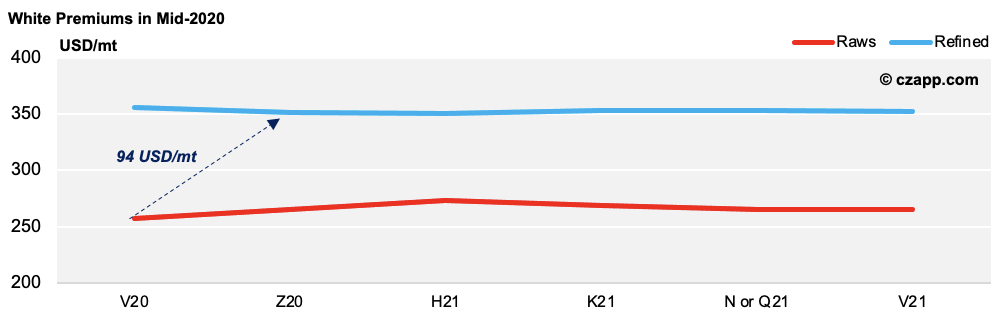

- This time last year, a refiner looking to buy raws against the Oct’20 No.11 futures contract and sell the resulting refined against the Dec’20 No.5 futures contract could hedge at 94 USD/mt.

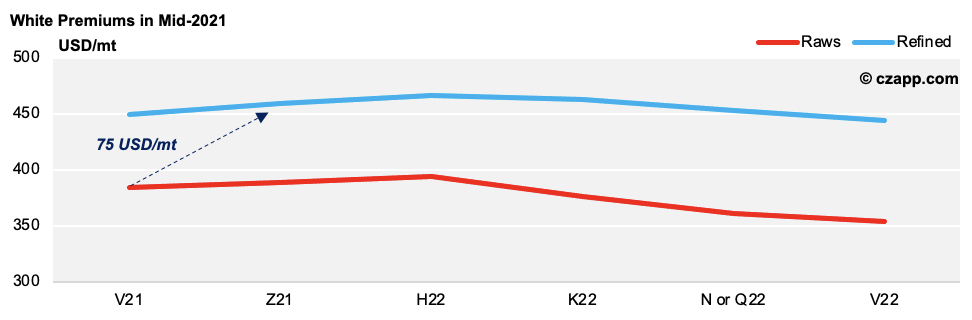

- But today, a refiner looking to buy raw sugar against the Oct’21 No.11 futures and sell versus the Dec’21 No.5 futures can only hedge at 80.26 USD/mt.

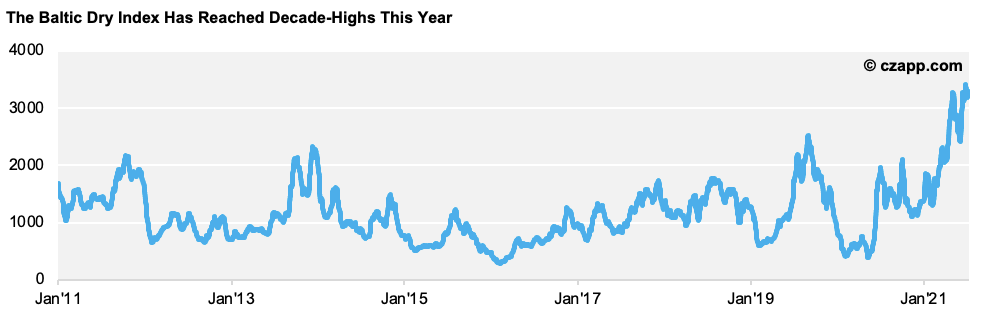

- The weak white premium isn’t the only problem; refiners are being hit twice because dry bulk freight is so expensive.

- · This means it’s more expensive for refiners to ship their raw sugar feedstock from the country of origin to their warehouses for processing.

- Last July, a refiner in the Indian Ocean region paid around 25 USD/mt for a spot 45k drybulk vessel.

- Today, that rate is closer to 60 USD/mt.

- The combined white premium and freight adverse effect of close to 55 USD/mt is a big deal for many refiners.

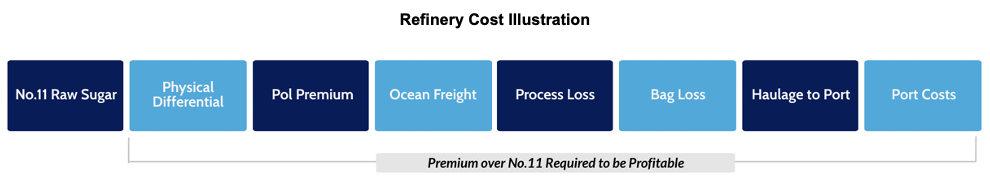

Calculating Refinery Profitability

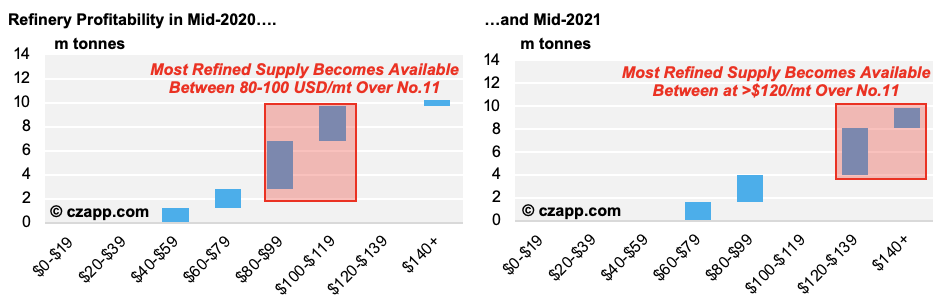

- We model profitability for major refined sugar producers around the world.

- We think the simplest way to express this is to show how much money they need in USD/mt above the No.11 futures in order to be profitable.

- We then show how much additional refined sugar tonnage will be available to the world for a given sum above the raw sugar futures.

- This gives a guide as to where the market needs to go to increase or decrease supply at any given moment.

- In January, most additional refined supply was available to the world market at 80-120 USD/mt over the raw sugar futures.

- Today, most supply becomes available at 120-150 USD/mt over the No.11.

Fragmented Refined Sugar Markets

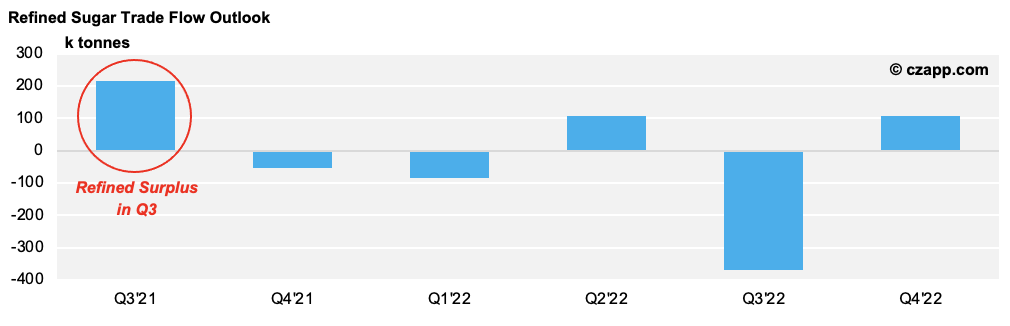

- The weak white premium shows that the world doesn’t need additional refined sugar supply at the moment.

- It’s signalling the most expensive refiners to slow their throughput and stop offering refined for sale.

- Indeed, we’ve heard anecdotally that some areas of the refined market are well-supplied.

- For example, there are rumours of afloat dry bulk white sugar vessels in the MENA region looking for a buyer.

- Meanwhile, enhanced COVID lockdowns in Thailand and Indonesia have hit sugar consumption in both countries, meaning increased Thai refined availability and decreased Indonesian refined demand.

- It’s clear some parts of the refined market need to run down stocks a little.

- But this isn’t the case across the whole world.

- The well-documented problems in the container market mean the white sugar market as a whole has become even more fragmented than normal.

- Each fragmented region has different supply and demand profiles, and these are reflected in differing physical values for each area.

- For example, spot Thai refined is quoted today at $35 premium to the futures, whereas Indian refined is closer to flat.

- Physical values contribute towards the refiners’ profitability, meaning refiners in regions with high physical values are probably doing fine.

What Happens Next?

- In the short term, we think refiners in regions with cheap physical values will need to slow throughput.

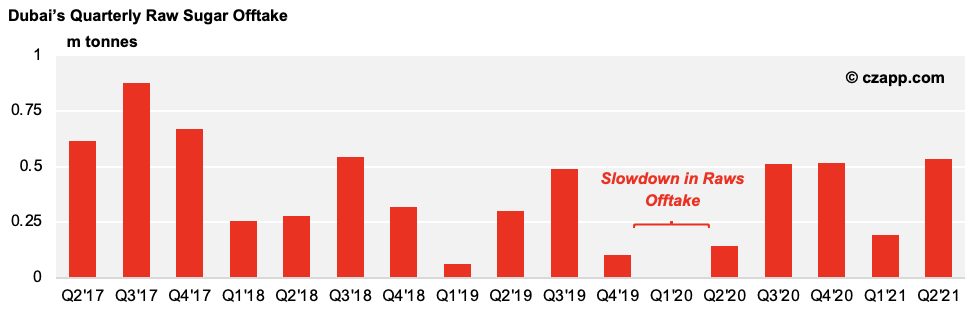

- We’ve seen this happen in the past, where the refinery in Dubai has stopped operating for months at a time as it waits for better market conditions.

- If some refiners choose to slow operations, this suggests there’ll be reduced demand for raw sugar in the near future.

- After all, the raw sugar market is close to four-year highs; if your refinery isn’t operating, what’s the incentive to buy more feedstock at high prices?

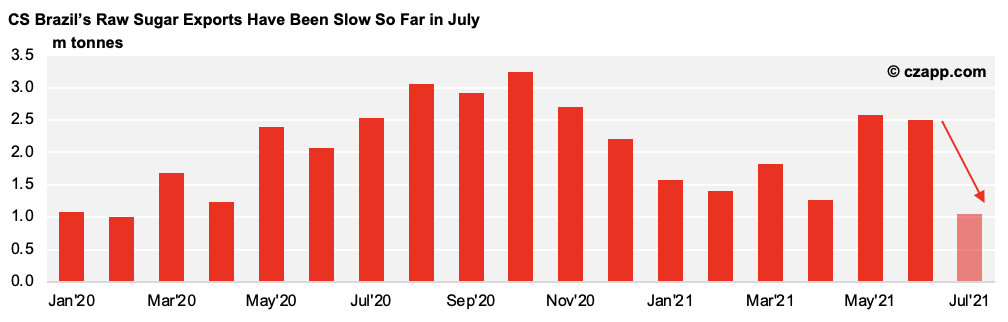

- Reduced refinery demand is bad news for raw sugar producers who are currently mid-crop, especially Centre South Brazil and Australia.

- Australian sugar producers will probably be fine; the industry has sufficient capacity to carry large volumes of raw sugar into 2022, if required.

- However, in Centre South Brazil, if raw sugar offtake is slow for several months, the logistical chain will back-up.

- First port warehouses will fill. Truck and rail movements to the port will need to slow down, meaning inland terminals will fill.

- As inland terminals are unable to receive more sugar, the warehouses at the mills will also fill with raw sugar.

- So, what’s the outcome?

- If the refined sugar surplus in the market resolves quickly and the refined sugar futures rebounds, refiners will start to operate at a higher throughput.

- The same could happen if dry bulk freight rates ease.

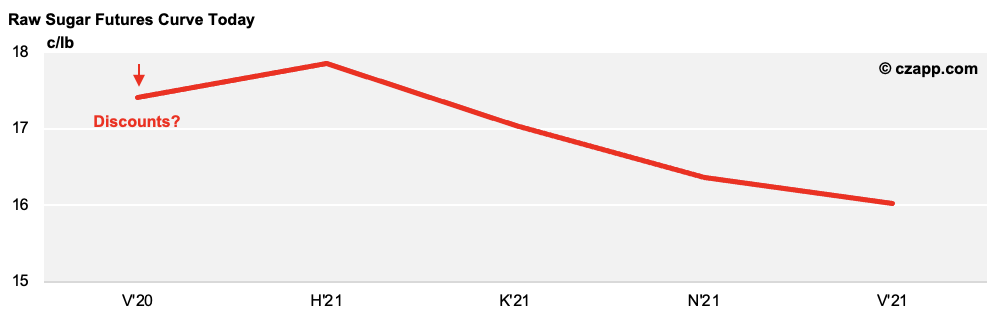

- Assuming the white premium stays weak and the freight market stays expensive, raw sugar physical values will continue to weaken in CS Brazil.

- Effectively, sellers will start discounting their raw sugar to try to make a sale.

- This has the potential to push the raw sugar spreads lower too, either to the point where it’s attractive for refiners to buy more sugar or to the point where the spread pays for the sugar to be stored in warehouses in Brazil into Q4’21 and beyond.

- After 15 months of rising sugar prices, is anyone really prepared for weaker raws prices?

Other Opinions You Might Be Interested In…

Explainers You Might Be Interested In…

- Czapp Explains: CS Brazil’s Sugar Industry

- CS Brazil’s Sugar Logistics