Welcome to the fifth part of Czapp’s course on freight

In the first episode we looked at the different ways that cargo can be moved through supply chains around the world. In the second, we looked at the different participants in the drybulk freight market. In the third we looked a t the ships themselves. In the fourth we looked at the contracts needed to move goods.

- Types of Freight

- Drybulk Ocean Freight: Who Does What?

- Drybulk Vessels, Cargoes and Routes

- Drybulk Freight Contracts

- Freight Costs and Price Risk Management

- Container Freight

Now, we will look at how everyone in the supply chain can control their costs and manage any price risk.

Imagine you run a food company and need to ship a range of inputs to your factory gate. You therefore have a large freight requirement each year and would like a way to control the costs of your freight. Forward Freight Agreements (FFAs) might be able to help.

FFAs

A freight contract is where two parties agree to settle a hire rate for a specified quantity of cargo or a type of vessel for one or more shipping routes in the dry bulk market at a certain date in the future.

What does that mean in the real world? Imagine you’re the raw sugar manager at a sugar refinery and you need 50k tonnes sugar to arrive at your factory gate each month. This sugar comes from overseas and is transported in a drybulk vessel.

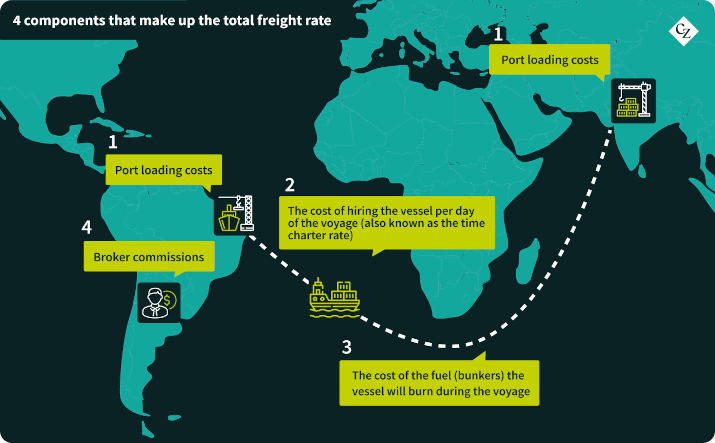

There are four components that make up the total freight rate:

- The cost of hiring the vessel per day of the voyage (also know as the time charter rate),

- The cost of the fuel (bunkers) the vessel will burn during the voyage,

- Port costs at load and discharge,

- Broker commissions.

The hire cost and bunker costs are typically variable, while the port costs and commissions are largely fixed.

You can buy the freight at the prevailing spot rate each month. But if prices rise then you have to pay more; this is what happened in 2020 and 2021.

Source: Refinitiv Eikon

Or you might want to hedge your hire rate and bunker costs.

The way to hedge the hire rate is to create an Forward Freight Agreement (FFA) for a mutually agreed price. In this way you now have certainty of the price you will pay for your vessel hire. If you can also hedge your bunker costs, you have nearly complete freight price certainty and can budget/plan accordingly.

An FFA is a freight derivative. If a shipowner and charterer agree an FFA they don’t have an actual physical vessel fixture between them, but have taken a market position on the direction of the hire rate for a future period. FFA contracts are cash-settled on expiry.

FFAs can be bought and sold between counterparties, either on an exchange or over the counter (OTC). Exchange-traded derivatives are standardized contracts are traded on a central marketplace and guaranteed through a clearing house. OTC contracts are negotiated directly between buyer and seller and may involve counterparty risk.

FFAs have precise contract specifications. They reference one of 4 indices quoted in the dry bulk market, each of which reference a size of vessel [link to previous explainer on vessel sizes]:

- Baltic Handysize (BHSI),

- Baltic Supramax (BSI),

- Baltic Panamax (BPI),

- Baltic Capesize Index (BCI).

Each index sets the benchmark for the daily hire rate of a vessel of that size for a specific list of routes.

The overall index price is comprised of a weighted average price of these listed routes, as determined on a daily basis by a panel of brokers.

The Capsize index is made up of 5 trip-charter routes and 5 time-charter routes, the Panamax 5 trip charter routes, Supramax 10 trip-charter routes and the Handysize 7 trip-charter routes. Each index is quoted in US Dollars per day, and traded in numbers of days for a given month. When used as a hedge the traded month should correspond to the shipment month of the underlying freight position and the number of days should correspond to the total charter time. FFAs are usually traded in multiples of 5 days.

How does this work in the real world?

A Buyer and a Seller agree to trade an FFA contract and they will agree on the period (calendar year and month, e.g. March 2023), the number of days per month within that period (e.g. 20 days) and negotiate a price. When the contract expires, if the agreed price is higher than the settlement price, the seller will compensate the buyer for the difference. On the other hand, if the fixed price is lower than the settlement price, the buyer will compensate the seller for the difference. The settlement price is the average of the daily settlement prices for the traded month of the contract. This is multiplied by the contract size (number of days traded) to give a final cash settlement value.

While FFAs allow users to hedge vessel hire rates, they are unlikely to provide a perfect hedge. Here are some considerations:

Price Settlement: Price is determined based on an average price over a period and may therefore differ from the spot hire price on the settlement date.

Routes: An index of routes won’t be a perfect USD/tonne hedge for a specific route.

Basis Risk: The price of the FFA and the underlying freight may differ due to imbalances in supply and demand between the derivative and underlying.

The freight team at Cz has expertise in helping customers manage their freight price risk. If you’d like to control your freight costs, please speak with Jonathan, Richard or Annie today.

We are also working with customers to help manage container freight price risk. Prices of the liner routes can be mutually agreed ahead of time (much like the FFAs), enabling an extra control on input costs.

Laytime, Demurrage and Despatch

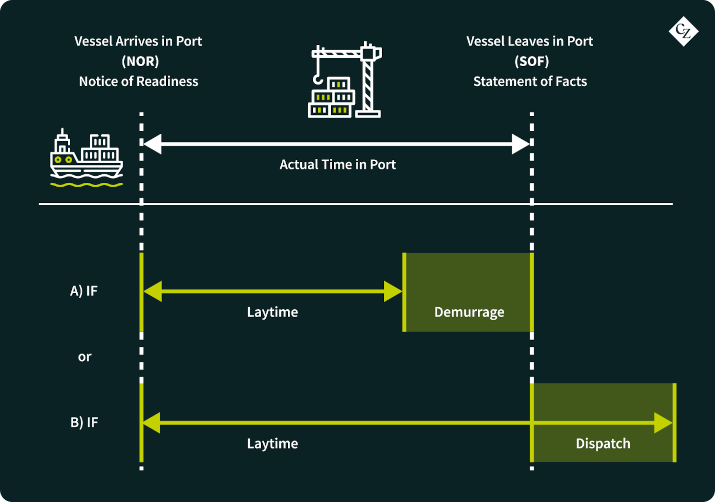

Laytime is the period of time agreed that between ship owner and charterer that a vessel will load and unload cargo.

A master of a vessel must give a notice of readiness (NOR) to the charterer when a ship has arrived at a port of loading or discharge. The date and time of the NOR determines when laytime begins. At the end of a stay at port the port agent draws up a Statement of Facts. This sets out a log of events from the ship’s stay at port. The Statement of Facts enables a timesheet to be made and signed by the ship’s master and the shipper/receiver of the cargo. At this point demurrage or despatch can be calculated from laytime.

Source: Shutterstock

Demurrage is the charge that the charterer pays to the shipowner if its operations delayed loading or unloading. Officially, demurrage is a form of liquidated damages for breaching the laytime as specified in the charter party contract.

Despatch is the reverse of demurrage. When a charterer requires use of a vessel for less time than the laytime allowed, they may be owed despatch from the shipowner to cover the time saved. Despatch is normally paid at 50% of the demurrage rate, but the exact rate for each contract is specified in the charterparty

Demurrage and despatch also occur in the container market as well as the drybulk market, where a container is supplied to a merchant for a specified period of time. If the container is used for longer than allowed, container demurrage is charged.

Here is a list of some of the contract jargon which might be relevant to laytime, demurrage and despatch calculations:

SHINC – Sundays and Holidays included.

PMSATSHEX: Saturday afternoons, sundays and holidays excluded.

PWWD: per weather working day

WICON: whether customs cleared or not.

WIPON: whether in port or not.

WIBO: whether on berth or not.

LAYCAN: laydays cancelling – the date the ship is required to present for loading.

Marine Insurance

This is insurance to cover the possible loss or damage of ships or cargo. Typically, marine insurance is split between vessels and cargo. Vessel insurance is often known as Hull and Machinery insurance. Cover is either on a voyage or time basis. Voyage basis covers transit between two ports specified in the insurance policy. Time basis covers a set period.

Cargo insurance covers the risk of damage or loss to the vessel’s cargo.

In the past, a marine policy only typically covered 75% of the insured party’s liability towards 3rd parties. Shippers and shipowners were still partially liable for possible collisions, wreck removals, environmental pollution and liability to the cargo-owner for damage to cargo.

Therefore, it was common in the 19th century for shipowners to form mutual underwriting clubs, known as Protection and Indemnity (P&I) Clubs, to insure the remaining 25% liability among themselves. These P&I clubs still exist today. The clubs admit shipowners as members while charging an initial premium. These funds are then used to purchase reinsurance. Supplementary calls for funds can be made if a loss demands it.

Czapp Explains – Freight series: Types of Freight