Opinion Focus

- The last few years have been full of ups and downs for the container industry.

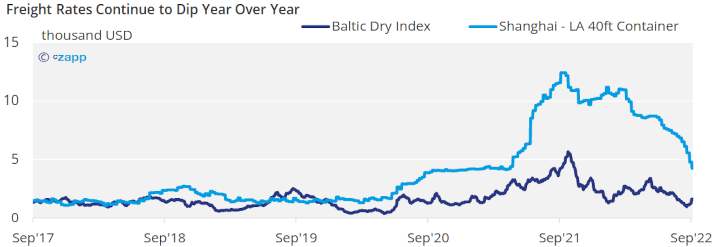

- Prices are now falling fast ahead of a potential global recession.

- At such a complex moment, shipping companies must also contend with IMO requirements to decarbonise.

IMO 2023 is fast approaching and for shipowners, that means the next few months are filled with uncertainty and potentially costly upgrades. With the price of freight dropping ahead of a global recession and a weakening in demand, placing extra cost burdens on the industry may not be viable.

IMO Tightens Regulations

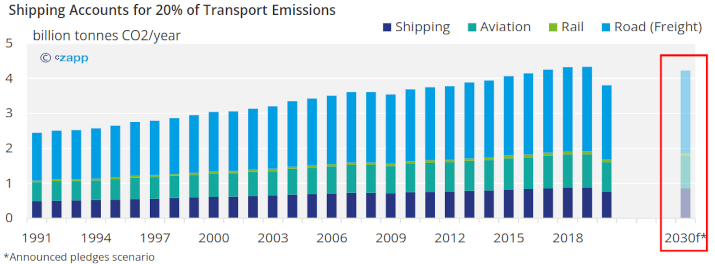

The international shipping industry is responsible for a significant amount of CO2 emissions each year.

Source: International Energy Agency, World Resources Institute

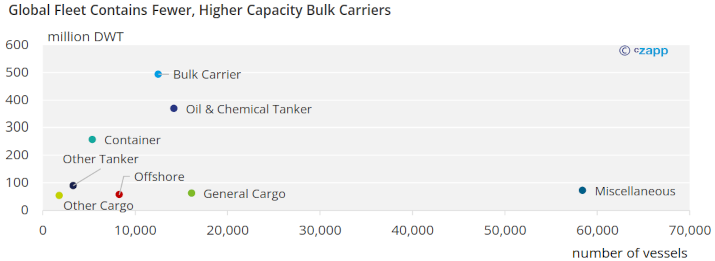

According to the IMO, there are just under 120,000 vessels in the global fleet with a total capacity of almost 2 billion deadweight tonnes.

Source: IMO

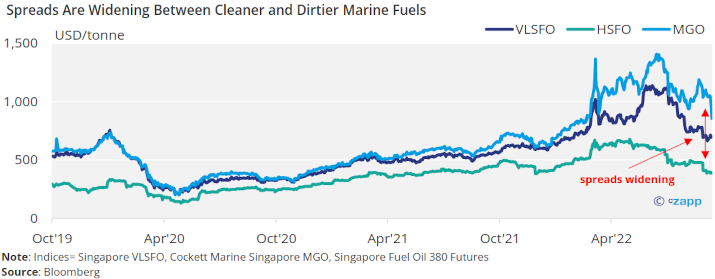

The most widely used fuel in for these vessels has typically been an extremely heavy and viscous heavy fuel oil that comes from the residue of the oil refining process. This emits significant amounts of pollutants and in 2020 was targeted by the IMO.

The IMO was set up in 1948 to address safety-related and environmental issues and has since adopted a number of conventions to improve standards within the international shipping industry. One major IMO milestone in 2020 capped emissions from marine fuels to just 0.5% sulphur – a level exceeded by heavy fuel oil. E+08.

After that point, shipowners had two choices: continue to use a lighter bunker fuel known as gasoil (which is more expensive than heavy fuel oil) or retrofit ships with a “scrubber”. This can essentially reduce sulphur content in the cheaper heavy fuel oil, but the process of conversion is extremely pricey.

Industry Moves to Decarbonise

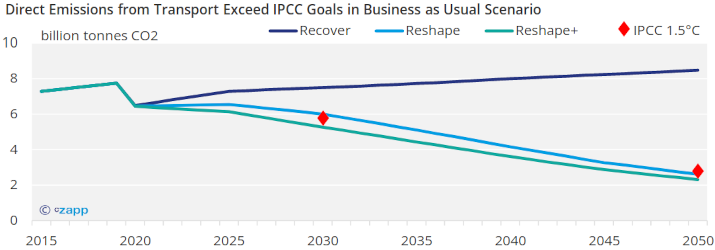

According to the International Energy Agency, 2019 emissions from shipping reached 870 million tonnes of CO2. To meet the IMO’s targets, levels would need to reach 522 million tonnes of CO2 by 2030 and 261 million tonnes by 2050.

The OECD’s ITF Transport Outlook estimates this can only happen in a scenario where governments not only implement ambitious decarbonisation policies but also leverage opportunities for transport decarbonisation.

Note: Recover, Reshape and Reshape+ refer to the three scenarios modelled by OECD’s ITF Transport Outlook; IPCC 1.5°C refers to emiss ions reductions required to keep global temperature rise under 1.5°C

Source: OECD

As shipowners look at low-cost, minimally disruptive ways to reduce their emissions, there are a few solutions they can implement.

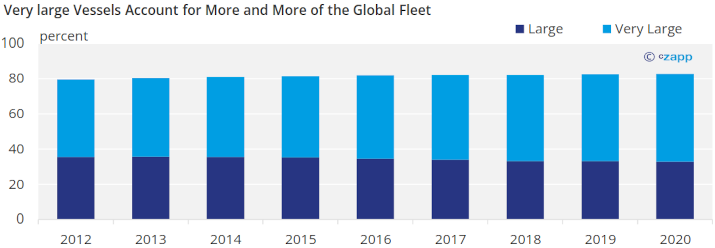

In spite of growing demand, the shipping industry is becoming more efficient by using increasingly larger vessels. This means fewer journeys, reducing emissions.

Source: Equasis

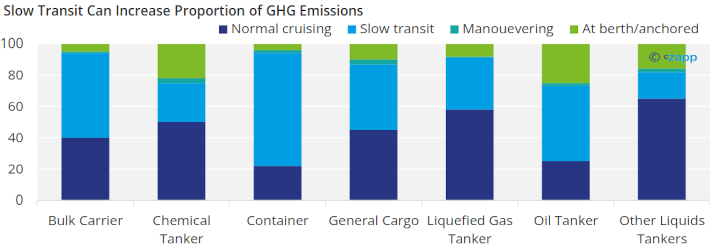

Another tactic the industry has used is by slowing cruising speeds. While this can improve greenhouse gas emissions from certain vessels such as chemical tankers, liquids tankers and liquefied gas tankers, slow transit actually generated more greenhouse gas emissions than normal cruising for bulk carriers, containers and oil tankers in 2018.

Source: IMO

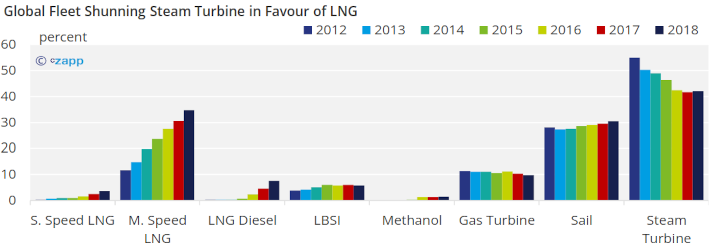

In the longer term, the industry is looking at alternative fuels beyond VLSFO. From 2012 to 2018, the penetration of LNG-powered ships in the global fleet rose significantly. The sulphur content in LNG is minima but the cost of conversion of vessels can run into tens of millions of dollars. Natural gas prices are also on the rise.

Note: Figures add up to more than 100% as some vessels fall into more than one classification.

Source: IMO

Liquid biofuels can be combined with fossil fuels to mitigate emissions. However, this also throws up questions about food security, especially given the current landscape. Fuel blends of up to 20% do not require engine modification but may require additives.

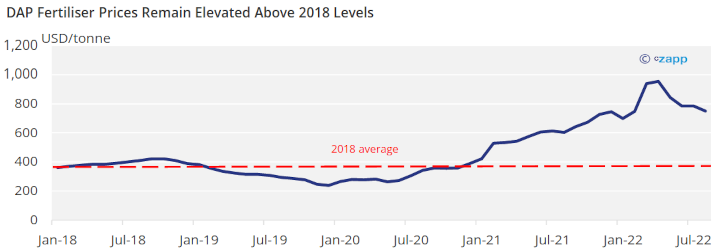

Another option is ammonia, which is already widely produced with a global capacity of 180 million tonnes per year. The main use of ammonia is in fertiliser, though, which again throws up food security questions, especially given the elevated cost of fertiliser.

Source: World Bank

Shippers Expect More Upheaval

While this was a difficult period for shipowners, there are further requirements to come. The IMO has pledged to reduce CO2 emissions by 40% of 2008 levels by 2030, and by 70% of 2008 levels by 2050. This poses a challenge for the shipping industry.

The next milestone for IMO regulations will come in January 2023. At this point, vessels will be required toimplement an enhanced Ship Energy Efficiency Management Plan (SEEMP), determine their Carbon Intensity Indicator (CII) and ensure the vessel falls within guidelines of an Energy Efficiency Existing Ship Index (EEXI).

But although these changes take place in just a few short months, there is still uncertainty over how the regulations will be met and how they will be enforced. There are also questions over how much improvement the rules will actually make.

For example, CII requirements could mean that higher-emitting ships will be allocated to longer voyages, meaning their carbon intensity drops. Lower-emitting ships would likely be assigned to shorter voyages. In the short term, this is likely to increase CO2 emissions rather than lower them in the short term.

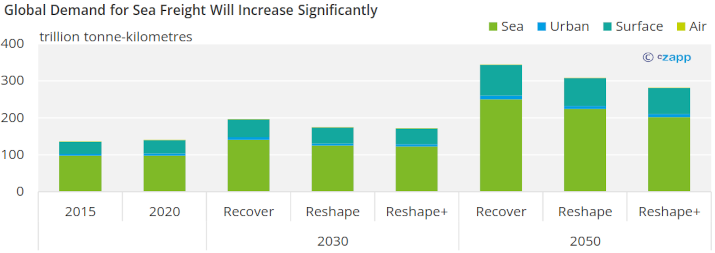

Another concern is that, as time goes on, the global vessel fleet will grow. Reducing emissions by 70% based on a 2008 baseline will be complicated by demand growth. By 2050, global sea freight demand could increase by as much as 155% compared to 2020.

Note: Recover, Reshape and Reshape+ refer to the three scenarios modelled by OECD’s ITF Transport Outlook

Source: OECD

And given that the transition requires significant amounts of investment, there are question marks over whether this will be feasible in a lower-price environment. Since its September 2021 peak, the benchmark rate for a 40-foot container from Shanghai to Los Angeles has lost over 65% to reach USD 4,252.

Concluding Thoughts

- The global shipping industry must reduce its global emissions.

- But questions remain over the timeline and implementation of the changes.

- Companies have an opportunity to adopt innovative solutions, but the next few years are likely to be costly for shipowners.

- This comes amid a drop in freight prices, putting extra strain on margins.

- There is no fool proof alternative to high sulphur fuel oil but some short-term options are viable.

- Shippers will continue to be pressed between reducing carbon intensity and maintaining margins.