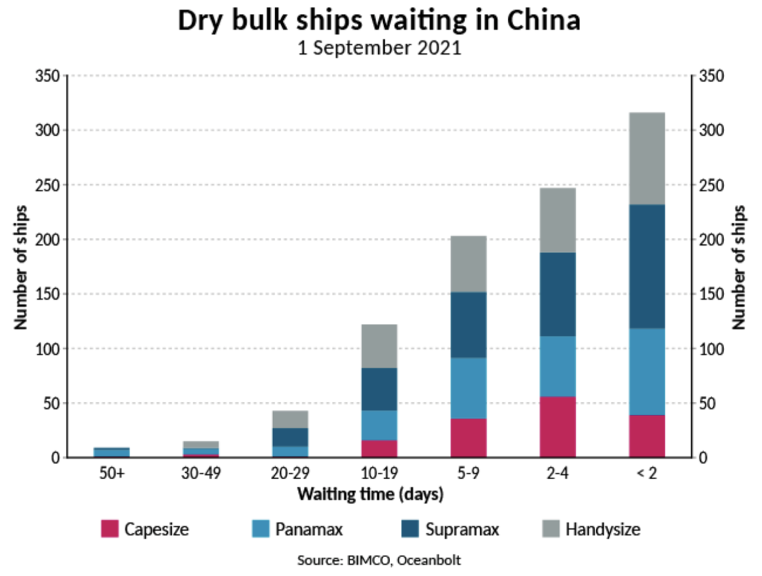

- COVID cases are worsening in some parts of the world.

- With this, ports are facing disruption as quarantine and testing requirements tighten.

- This is draining dry bulk capacity and supporting vessel owner earnings.

Demand Drivers and Freight Rates

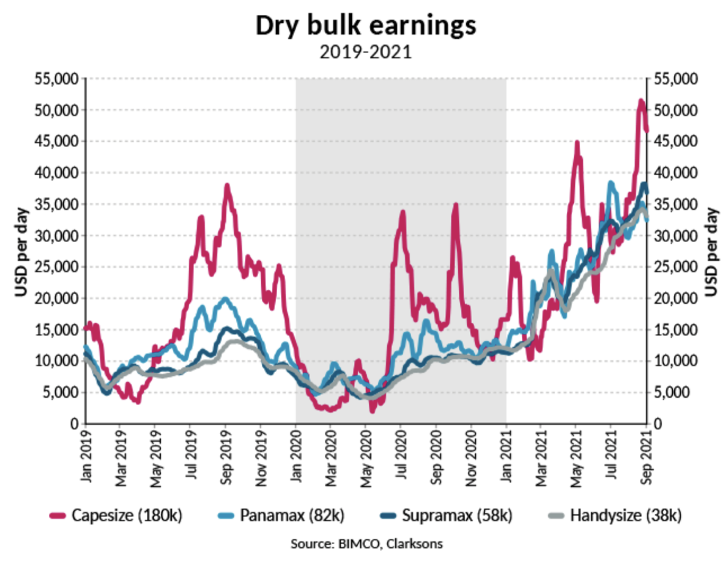

The dry bulk shipping industry continues to enjoy a bumper year, with average earnings continuing to outshine any profits made in the past couple of years. As is often the case, Capesizes are taking the spotlight, with recent earnings peaking above 50,000 USD/day. A much more consistent and stable increase is recorded for Handysize and Supramax ships. These saw average earnings rise to 33,087 and 36,832 USD/day, respectively, on the 3rd September. On the same day, a Panamax ship could earn 32,445 USD/day.

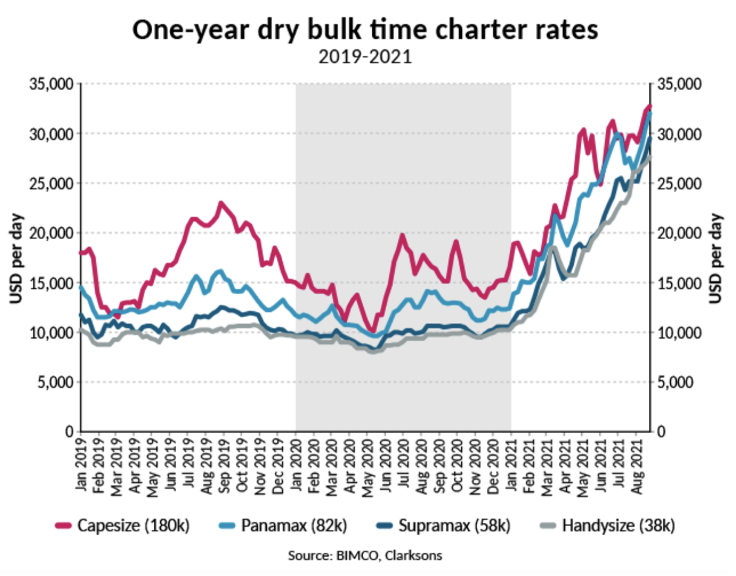

Time charter rates underline the current strength of the market, with charterers currently paying double, if not 2.5 times as much, at the end of August compared with the start of 2021. A one-year time charter on a Capesize ship at the start of the year would have brought owners 16,500 USD/day. By the 27th August, the figure was USD 32,750. Supramax ships have recorded the largest increase, with one-year time charter rates rising by 179.3% since the start of the year to 29,500 USD/day.

The high freight rates can be partially attributed to the restrictions and problems at ports due to the pandemic, which are tying up ships for longer than usual. On the 1st September 2021, 674 dry bulk ships had been waiting in China for two days or more. On the same day in pre-pandemic 2019, only 287 dry bulk ships had been waiting this long.

As an example of what this means for an individual trade, Oceanbolt data for ships sailing from Port Hedland (Western Australia) to Qingdao (China) shows that the average time for the journey (including the wait time at the load and discharge ports) has risen by 22.7%. In July 2021, it took an average of 33.5 days, while in July 2019 it could be completed in 27.3 days.

As well as congested ports, the recent pick-up in Brazilian iron ore cargoes to China has helped lift the Capesize market. In August, 21 iron ore cargoes were offered on the spot market, compared to 11 in July and the highest weekly number of cargoes since April (source: Commodore). During the first seven months of the year, Brazil exported 198.8m tonnes of iron ore, a 10.8% increase from last year and up 1.0% from 2019. However, it remains 15.0m tonnes lower than the record-high exports of 213.7m tonnes that were recorded in the first seven months of 2018.

65% of Brazilian iron ore exports during the year to date have gone to China, with volumes on this trade growing by 6.2% over this period. Here, volumes of iron ore have grown compared to 2018, as China has taken a larger share of the total. This is clearly good news for dry bulk demand; the larger the share heading to China, the higher the tonne mile due to the long distance.

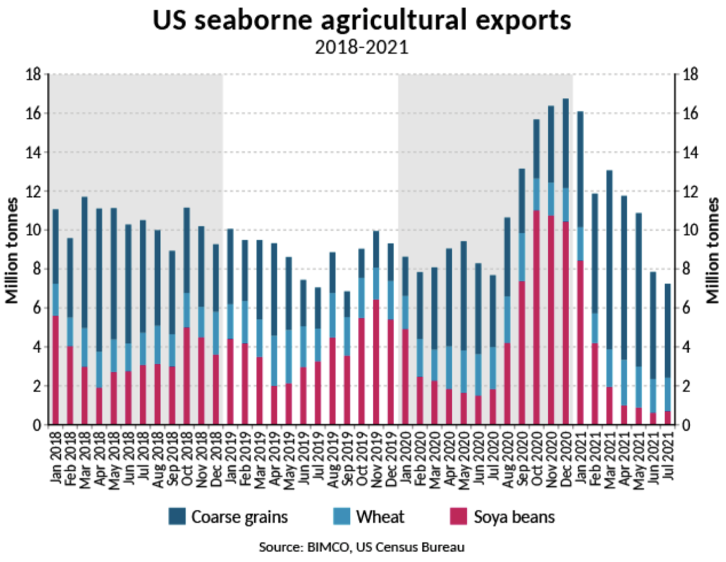

There has also been strong growth in grain exports from the world’s largest exporters. Grain exports from the biggest exporters have grown by 6.3% to a record 162m tonnes in the first six months of the year. The driver of this growth has been the US, which has seen its grain exports rise by 39.3%, jumping from 51.3m tonnes in the first half of last year to 71.5m tonnes. By contrast, exports from Brazil and Argentina have declined. Brazilian exports are down by 0.3% to 61.5m tonnes, while those from Argentina have fallen by 26.3% to 29.0m tonnes.

US coarse grains exports have seen the highest growth, up 19.2m tonnes (+67.1%) in the first seven months of the year compared to the same period in 2020. These additional volumes are the equivalent of an extra 257 Panamax loads (75,000 tonnes). Just behind in terms of volume growth are US soya bean exports, which have had a strong off-season, with exports in the first six months amounting to 17.8m tonnes, a 7.8% increase from last year.

The new US marketing year began in September, and exports of soya beans will once more start to increase. Compared to the start of the 2020/2021 marketing year, outstanding sales are much lower, currently standing at 17.8m tonnes, compared with 29.4m tonnes on the 1st September 2020. While more sales will soon be added to the current level of outstanding sales, it’s unlikely volumes in the 2021/2022 season that’s now underway will reach the 60.3m tonnes of soya beans that were exported in the 2020/2021 season.

Fleet News

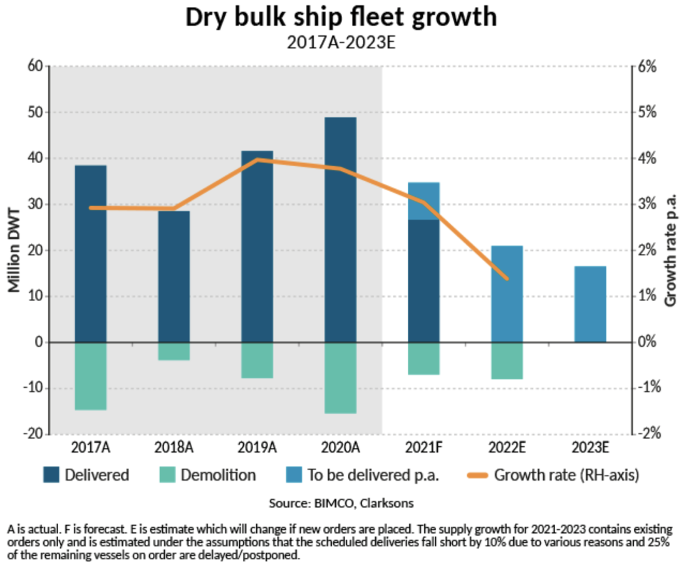

Around three-quarters of the dry bulk deliveries expected for 2021 have arrived, adding 26.7m DWT of capacity and bringing the total fleet to 934m DWT. BIMCO thinks the fleet will grow to 940m DWT over the coming months, which will result in fleet growth of 3% this calendar year.

Of the 26.7m DWT delivered so far this year, half came from the 61 new Capesize ships, of which 51 have a capacity of 180,000 DWT or more, with ten of these exceeding 300,000 DWT.

At the other end of the lifecycle, only 4.8m DWT of capacity has been demolished. By the end of the year, BIMCO expects demolition to reach around 7m DWT, less than half of what was removed from the market in 2020, as the earnings potential for ships has incentivised owners to keep their ships sailing. This once again proves that the strength of the freight markets has a much greater influence on demolition than steel prices.

The summer months have seen the dry bulk orderbook grow by 67 ships, as 5.7m DWT was ordered in June through August. All but one will be delivered in 2023 and 2024. The orders include 2.3m and 2.5m DWT of Capesize and Panamax ships, respectively.

Including all orders, the orderbook currently stands at 53.9m DWT, a significant decrease from 71.6m DWT in August 2020 and 97.8m DWT in August 2019, as ships have been delivered faster than new ones are being ordered.

Outlook

As we approach what is seasonally the strongest part of the year for dry bulk, the market is looking promising, and operators have already been recording solid profits so far this year.

While countries enforce quarantine and testing requirements, and ports face sudden disruptions due to local and regional outbreaks, the congestion that is draining the market of capacity will continue to support earnings in the dry bulk market. The market is expected to stay strong into 2022 until the factors that are currently beneficial to the market such as congestion and pandemic related delays, spill-over from the red-hot container market, stimulus driven demand and strong growth in the manufacturing sector become less so.

This positive outlook is also reflected in second-hand prices, which have followed the freight markets on an upward path. Compared to the whole of 2020, the price of a Capesize ship on the second-hand market has risen by 43.3%, based on disclosed prices so far this year. The average price of a Capesize ship currently stands at USD 28.4m, with an average age of 9.4 years. All other second-hand dry bulk ships have also seen average prices rise by more than 40% year to date compared to 2020, with Handysize ships rising 68.4% to USD 12.1m (average age: 9.9 years).

In the longer term, however, the underlying volumes may be less supportive. After strong growth in the first half of the year, the Chinese government seems keen to clamp down on the steel and other heavy industries to limit emissions. One big question is how strictly these measures will be enforced and whether they will start to constrain economic growth. The two largest dry bulk goods imported by China in terms of volume, iron ore and coal, have both fallen year-on-year during the first seven months of the year. Iron ore imports have fallen by 10.5m tonnes (-1.5%) and coal imports are down by 30.4m tonnes (-15.0%). Imports of both goods stood at a record high in 2020, and as government restrictions come into play, it seems increasingly unlikely that these levels of imports will be repeated.

Other Opinions You Might Be Interested In…

- What’s Really Happening in the Container Market?

- Ask the Analyst: The Exchange, Futures and Physical Contracts

Explainers You Might Be Interested In…