Opinion Focus

- Ukraine has been relying on piecemeal rail export of its grains through Romania and Poland.

- Congestion has been building up across Eastern Europe’s rail and road links.

- Now as Ukraine’s neighbours begin their own harvests, bottlenecks are likely to worsen.

Grains prices have been rising fast since February. The Russian invasion crippled Ukraine’s 20 million tonnes a year grains export capacity. With ports blockaded, authorities have been looking to use alternative routes, including sending grain by rail to neighbouring Poland and Romania. But the beginning of these countries’ own harvests threatens yet another bottleneck.

Wheat Season Approaches

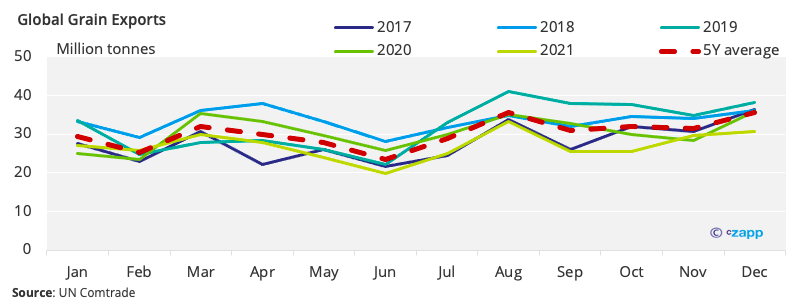

Global wheat exports tend to accelerate towards the end of the year. Over the past five years, the world has exported on average 27.9m tonnes a month in the first half of the year, compared with 32.3m a month in the second half.

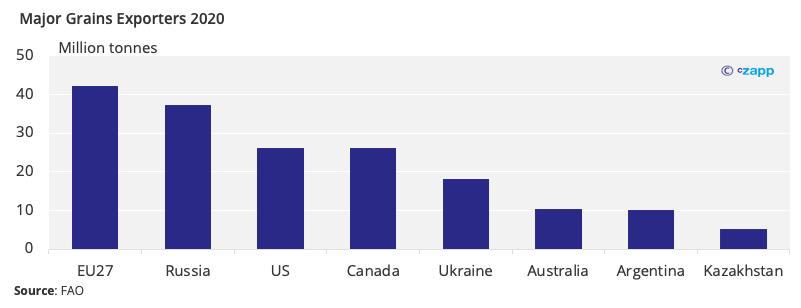

This is partly due to harvest seasons of each country. Within the EU27 — collectively the world’s largest grains exporter – grains harvesting begins in mid-May and ends in December. Russia’s harvest takes place between July and August. The US harvest season is May to October, while in Canada wheat ripens around August or September.

Given that these are the largest grains exporters globally, sales tend to be backloaded toward the end of the year.

Fewer Grains Leave Ukraine

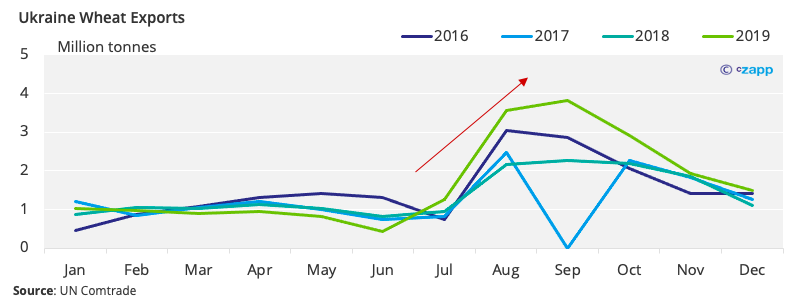

According to Reuters, Ukraine managed to export 1.5 million tonnes of grains in May compared with 1 million tonnes in April. The goal is to increase this volume to 2 million tonnes in June – the maximum capacity the rail routes can withstand, according to First Deputy Agriculture Minister Taras Vysotskiy.

But these grains have been forced to transit through neighbouring countries Romania, Poland and Bulgaria due to Russian blockades of the Black Sea. Ukrainian seaports are capable of exporting 5 million tonnes a month of grains.

Neighbouring Countries Enter Harvest Season

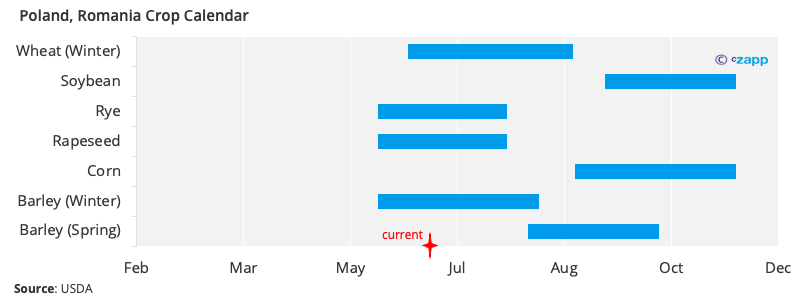

In Poland, June marks the beginning of the harvest season for winter barley, rapeseed, rye and winter wheat. Romania and Bulgaria are also beginning to harvest winter wheat and barley in the same month.

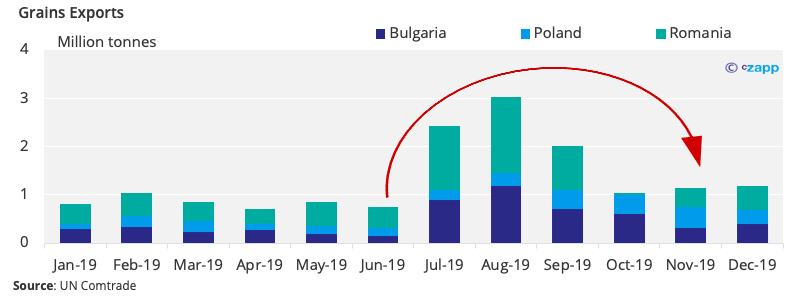

This harvest season also coincides with a higher level of exports. Typically, exports from these three countries ramp up in the months of July, August and September.

Until this point, two routes have been established to move Ukrainian grain: through Poland and Romania. Most of the grain going to Romania is transported by rail to ports on the Danube and loaded onto barges to be taken to the Black Sea port of Constanta. Some grains are transiting through Romania and going on to Bulgaria for export. All of these processes are costly and complex for a variety of reasons.

Constanta has the capacity to load and unload 100 million tonnes a year of cargo. However, its surrounding infrastructure has become a concern. With summer vacations approaching and motorists heading for the Black Sea resorts, officials are concerned that roads will become more congested, meaning truck transport has reached capacity for the time being.

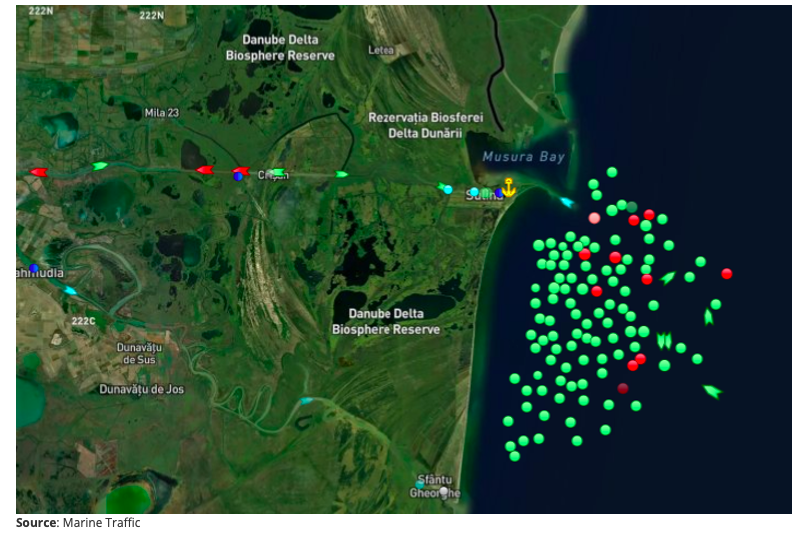

Additionally, the neighbouring Sulina Canal – used to gain access to the inland ports of Reni and Izmail in Ukraine and Giurgiulesti in Romania – has experienced significant queues. Ship tracker Marine Traffic shows over 100 vessels waiting outside the canal as of June 23.

These difficulties have been exacerbated by rail congestion, which means cargoes are delayed in reaching the port of Reni. In some cases, vessels have arrived at the port before the grain intended for loading.

Due to congestion, there is now a lack of barges to transport cargoes from the inland ports to Constanta. Barges are by far the most efficient way to move the grain, with a capacity to transport 3,000 tonnes of grain per barge. In comparison, one 600m long train can carrying 1,900 tonnes.

Now, as Romania gears up to harvest and transport its own crop – on average 1.3 million tonnes per month between July and September – the issues are likely to worsen.

Poland, Germany May Hold the Answer

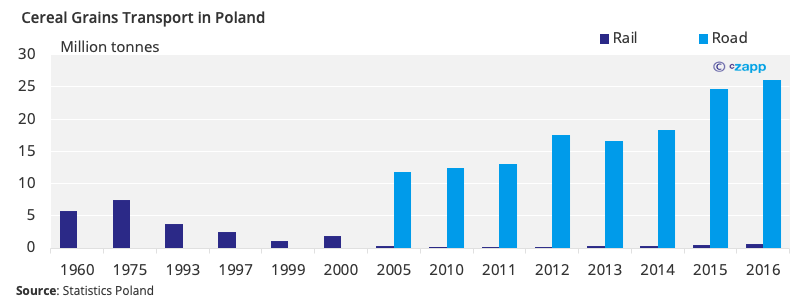

Poland typically exports very little of its grain, but it relies on its rail and road network to distribute its products throughout the country. It is much more common in Poland for grains to be transported by truck, despite the country’s dense rail network.

This is mainly due to Poland’s fragmented grain production, meaning it isvdifficult to achieve the critical mass necessary for rail transportation to be viable Ukrainian grains would then have access to the largely unused Polish rail grain transportation network, even during the Polish harvest. Ukrainian shipments would likely be large, continuous and transported long distances.

Other considerations also need to be taken into account. Poland’s intermodal infrastructure remains uncompetitive, according to a November 2021 report by the Polish Road Transport Institute Foundation (PITD). Plans suggest that grain cargoes are earmarked for transit to the ports of Gdansk and Gdynia but even before the war in Ukraine, Polish end terminals often do not have enough tracks to accept trains for unloading.

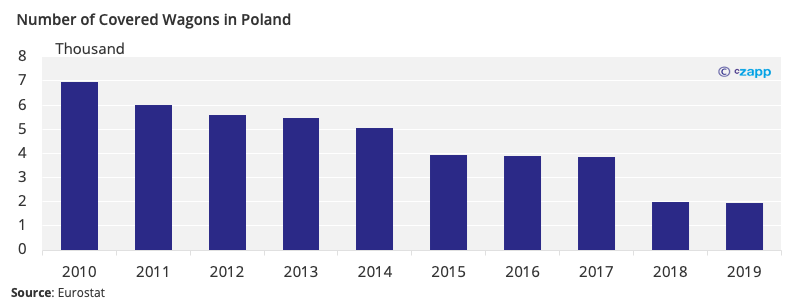

There is also the question of whether Poland has enough grain wagons to move Ukrainian products. According to Eurostat data, the number of covered wagons in Poland has been decreasing over the years. As of 2019, there were just 1,945.

If the congestion at Poland’s ports remains high, Germany is prepared to step in to try to transport the grain via an alternative route. The Ambassador of Germany to Ukraine Anka Feldhusen told Ukrainian news outlet Ukrinform that the German railway is working with Ukrainian partners to try to find solutions.

A spokesperson for German rail operator Deutsche Bahn told Czapp that the company aims to expand the several grain trains a day it is running through Europe with its cargo subsidiaries in Poland and Romania. “The aim is to establish viable connections to the seaports of the North Sea and the Black Sea and Mediterranean,” the spokesperson said. “Preparations for the expansion of grain transports are in full swing at European level with our partners.”

Regardless, the track gauge change at the Poland-Ukraine border will continue to cause congestion. The border region contains very few storage or transfer facilities, meaning whole cargoes would have to be unloaded and reloaded, causing delays.

Impacts Extend Further

The risk of fewer grains able to be exported from Eastern Europe is compounded by crop concerns due to adverse weather. France, a major wheat producer, has experienced record high temperatures this summer, jeopardising the wheat crop. Spain and Italy’s wheat production have also been threatened by extreme weather events. In the US, the wheat crop experienced a dry winter followed by a spring that was too wet for sowing.

This month, estimated wheat and barley yields for harvest 2022 have been cut for the third consecutive month by the European Commission. According to the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board (AHDB), this would cut yields to below the five-year EU average.

There are also concerns over China’s wheat crop, which a Chinese agricultural official said in March could be “the worst in history” due to a soggy planting season. India has also banned wheat exports, placing more strain on global supply.

This will have an effect not only on wheat supply but also meat. Much of the global crop harvested in September and October are destined for winter livestock feed. If grain shortages persist, millions of animals destined for consumption are at risk of starving.

Concluding Thoughts

- Authorities will continue to struggle to get grain out of Ukraine.

- The upcoming harvest will put even more strain on already saturated logistics infrastructure across Eastern Europe.

- One viable option would be to expand rail transit through Poland and into Germany.

- But there are questions over whether there are enough locomotives, rolling stock, crews and paths to do so.

- Deutsche Bahn, the German railway, said it is working with its subsidiaries in Poland and Romania to address issues.

- The bottlenecks, combined with extreme weather events, are throwing serious doubt on future food supply.

Other Insights that may be of interest

What the Energy Crisis Means for Inflation & Commodities

Interactive Data Reports that may be of interest …

Consecana Panel

CS Brazil Weather Update