Insight Focus

- Egypt looks to boost wheat self-sufficiency with Black Sea flows down.

- It’s boosted sugar self-sufficiency in the past so has a blueprint to work with.

- Key issues surrounding water availability and lack of available land could hinder progress, though.

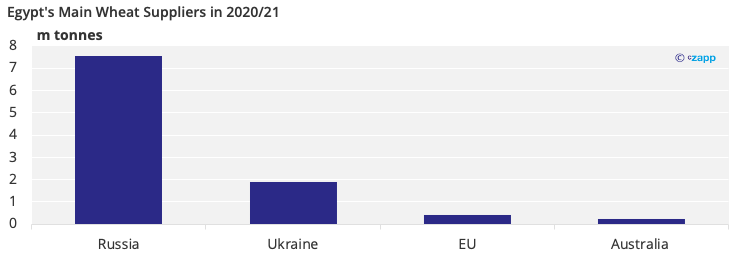

Egyptian wheat supply and food security have been hit hard by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. According to the USDA, around 82% of Egypt’s wheat has come from Russia and Ukraine in the last five years. Egypt is therefore looking to boost wheat self-sufficiency as it’s recently done with sugar. Will the sugar model work, though, with water and land availability tightening?

Wheat’s Significance in Egypt

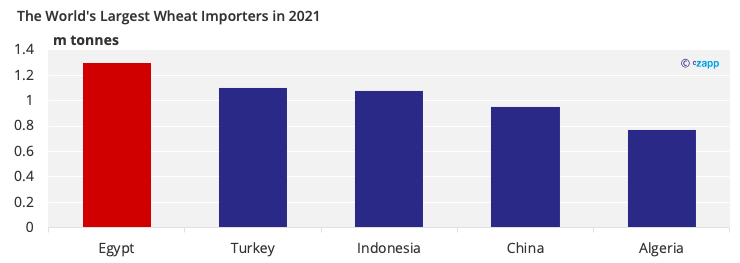

Egyptians rely on bread for over 35% of their carbohydrate intake, well above the global average of 18%. However, Egypt produces less than half of what it consumes, making it the world’s largest importer and extremely vulnerable to turbulence in the global grains market.

Egypt usually relies on Russia and Ukraine for its wheat as they are the cheapest origins. However, with the two at war, the world’s largest suppliers find themselves essentially removed from the market.

With this, the dearer origins have become even more expensive, spurring Egypt to look towards improved self-sufficiency, as it did with sugar.

Egypt’s Drive for Sugar Self-Sufficiency

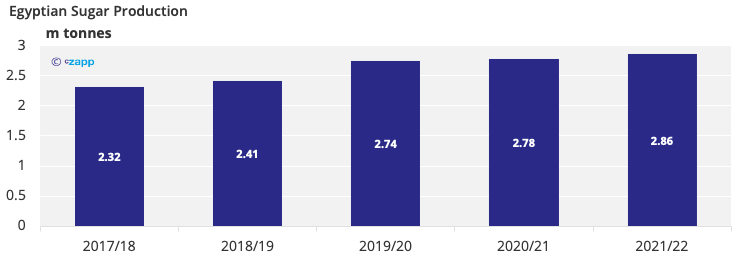

Between 2017/18 and 2021/22, Egypt boosted domestic sugar production by 460k tonnes (20%).

Helped by around USD 1 billion of UAE investment, Egypt was able to add 66k hectares more agricultural land, build 120 wells to improve water availability, offer cheaper inputs, and set up new beet processing plants, one of which is the world’s largest beet processing facility with a capacity of 900k tonnes/year. The arrival of the new facility saw the government allocate 76k hectares of land to grow beet for it to process, which has boosted the country’s sugar output.

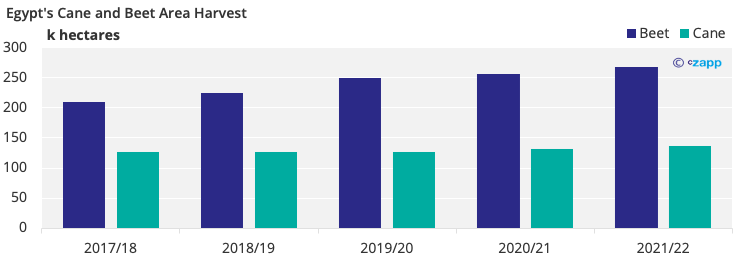

Between 2017/18 and 2021/22, Egypt’s beet area increased by over 26% to 267k hectares. Cane expansion was less successful in Egypt, with area growing by just 8% between 2017/18 and 2021/22 to total 136k hectares.

This is because the crop requires far more water than beet (1,500-2,500mm vs. 550-750mm per year) and water availability is poor in Egypt.

Egypt has 10.4m3 of renewable water available per capita, far below the global average of 5,724.5 m3/person. Even the Middle East and North African average is far higher at 525.7 m3/person. Egypt’s lack of water makes balancing the water requirements of the farmers and other citizens tricky.

Despite Egypt’s water trouble, cane productivity has improved to help production climb 13.6% between 2017/18 and 2021/22, compared to area, which grew by a smaller 7.9%. This growth was driven by increased use of fertiliser and the development of new cane varieties that are more resilient to disease.

The government also helps farmers procure fertiliser at 50% of the market rate, and Egypt is a large producer of fertiliser, meaning it’s less exposed to today’s high prices.

Can Egypt Do the Same for Wheat?

Egypt boosted sugar self-sufficiency in the space of a few years but doing so required heavy investment from the UAE.

If the investment is there, Egypt may be able to boost wheat self-sufficiency through similar means. The Egyptian government has already increased wheat procurement prices by around 22% this season so they now sit in a range of 366.10 USD/tonne to 374.60 USD/tonne.

It’s also encouraged farmers to plant a broader range of varieties to help yields. Investing in higher yielding cane varieties boosted sugar production and should have the same impact for wheat. Boosting fertiliser applications on wheat could also help too.

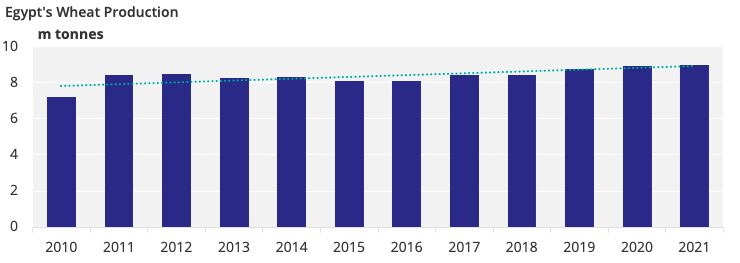

By 2023, Egypt hopes to be producing 10m tonnes of wheat a year, up 1m tonnes from today, cutting its reliance on imports.

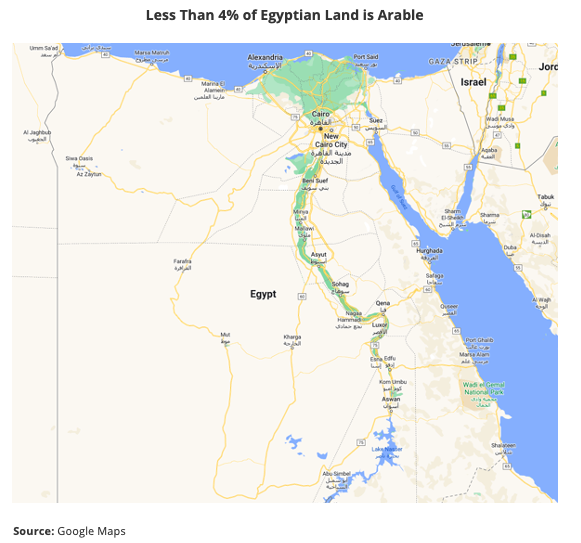

Egypt may run into trouble, though, as just 3.8% of its land is currently used for agriculture and more of its growing population have moved into previously farmed areas over the last few decades, hindering agricultural development.

Reclaiming land must therefore be a key part of any strategy. Land lost to urbanisation won’t likely be recovered, so the focus should be on desert and the Nile Delta. Converting desert into arable land is an expensive and timely process, though, which demands high levels of expertise.

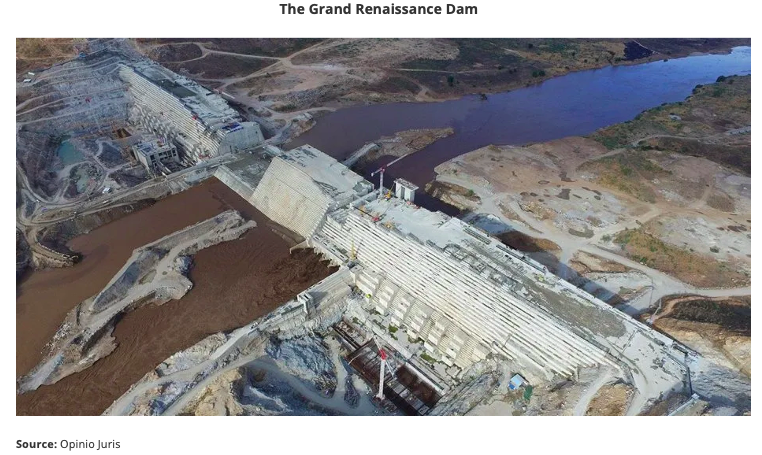

Beyond this, Egypt’s main water source, the Nile, is not as reliable as it once was as Ethiopia opened the Grand Renaissance Dam in 2020, which has increased the pressure on Egypt’s already scarce water resources.

This is bad news for wheat as a study conducted by Qatar-based Al Jazeera suggested that 14-36% of Egypt’s water supply could be temporarily lost over the next few years whilst the dam is filled, leading to the collapse of 50% of its farmland.

Wheat, like cane, is also a very water-intensive crop, demanding around 1,500 litres of water per kilogram produced. Egypt’s wheat farmers could turn to wells, but underground water is not the most reliable source as it can dry up in hotter weather. Also, the UAE-funded wells were most helpful with Egypt’s push towards beet expansion as beet demands a smaller 935 litres of water per kilogram produced.

This all suggests that Egypt’s drive for wheat production won’t be as successful, or simple, as that for sugar, especially as Egypt consumes around six times more wheat than it does sugar a year. Any push for improved self-sufficiency will have to be carried out on a much larger scale and, by extension, require more investment.

In the immediate term, we suspect Egypt will rely on its reserves of 3.9m tonnes, staving off the need for expensive imports. It should also diversify where its supply comes from and optimise its storage capabilities to help with longer-term stability.

Concluding Thoughts

- Egypt has shown that boosted self-sufficiency is achievable with largescale investment.

- It had greater success with beet sugar, as beet is less water-intensive than sugarcane.

- As wheat and cane have similar water requirements, Egypt may struggle to mimic previous successes.

- The task is also larger for wheat as domestic demand is stronger; there will be no overnight fix.

- Egypt must try though, as it can’t rely on cheaper Black Sea supply for the foreseeable.

- By boosting wheat production to 10m tonnes in the short term, immediate supply strains should ease.

Other Insights That May Be of Interest…

Russian Invasion Could Make India a Major Global Wheat Player

Russia Sanctions Weigh on Agri Trade Flows

Fertiliser Importers Caught in Russia-Ukraine Crossfire

Russia & Ukraine Grains Flows Likely to Be Disrupted into H2’22

Explainers That May Be of Interest…