Insight Focus

Last week, the European Commission announced new tariffs on Russian and Belarusian origin cereal, oilseed and animal fodder imports. The market accounts for about 10% of Russia’s exports in these categories, so where will they go now? And how will the EU plug supply gaps?

Background

Last week, the EU announced it would impose tariffs on Russian and Belarusian grain products, as well as excluding the countries from its quota system. This means these products that originate in Russia and Belarus will no longer be competitive for import into the EU.

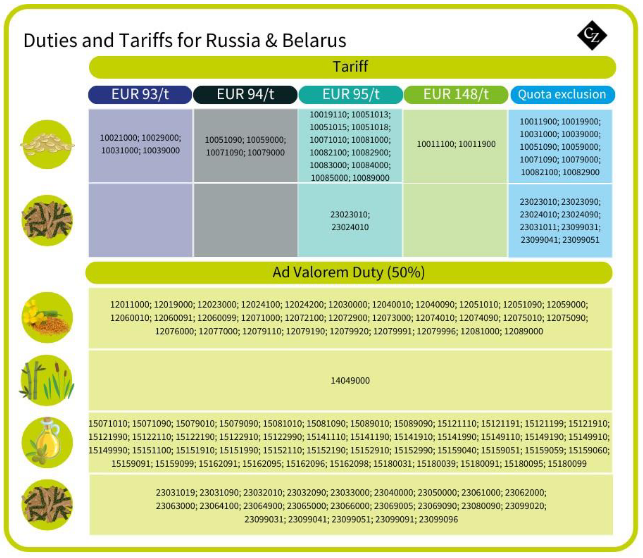

The decision affects the following categories under the Combined Nomenclature (CN). The CN is a tool used globally to classify goods into certain categories, which allows for more efficient global trade.

The European Commission said in its proposal, dated March 23, that “such tariff measures should help to prevent the Russian Federation from instrumentalising its exports of cereals, oilseeds and derived products to politically and economically weaken the EU.”

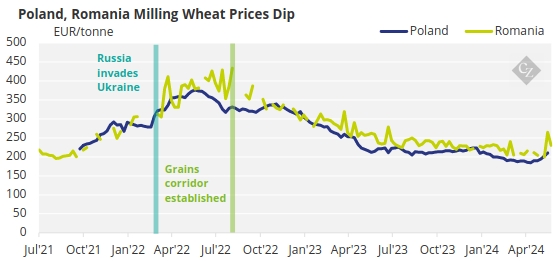

There have been several protests, particularly among the eastern countries of the EU27 such as Poland. Farmers in these countries claim an influx of grains from neighbouring Ukraine since the Russian occupation are depressing local grains prices.

Source: European Commission

This measure should go some way to reducing the amount of grains imports in the EU. It could also lift prices.

The European Commission also cited grain theft from Ukraine as a key reason for blocking Russian imports. “The Russian Federation is currently illegally appropriating large portions of cereals and oilseeds produced in the territories of Ukraine, which it currently illegally occupies, and is routing these supplies to its export markets as allegedly “Russian” products,” said the proposal.

The reasoning for including Belarusian products is due to its status as a key ally of Russia. The EC proposal said it had targeted Belarus “in view of its close political and economic ties with Russia and in order to prevent the illegal channelling of imports from the Russian Federation through the Republic of Belarus.”

The duties applied to cereal imports will be EUR 95/tonne, while oilseed imports will be subject to a 50% ad valorem duty. For certain items, Russia and Belarus will also be excluded from the EU tariff quota system (TRQ), which provides nominated countries with a certain allowance of duty-free imports every year.

How Significant Is This?

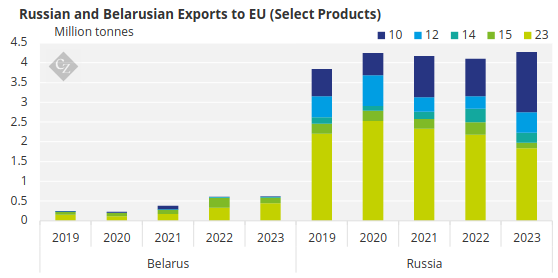

According to the European Commission, Russia exported 4.2 million tonnes of cereals, oilseeds and derived products in 2023, with a value of EUR 1.32 billion. Belarusian exports meanwhile were limited to around 610,000 tonnes in 2023, with a value of EUR 246 million.

Source: Eurostat

Note: Numbers in legend relate to CN codes

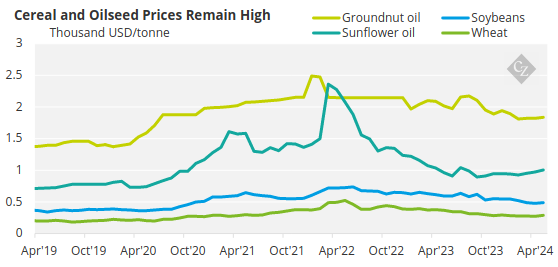

The price of cereals and oilseeds rose significantly after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Until now, Russia, as a major exporter, has been able to benefit from these higher prices as EU sanctions have so far steered clear of food products and fertilisers.

Source: World Bank

This is the first sign that the EU is willing to target food products as it tries to ramp up pressure on Russia, even amid some economic losses. The EC estimates the new measures against Russia and Belarus will generate a loss of up to EUR 15.77 million for the EU.

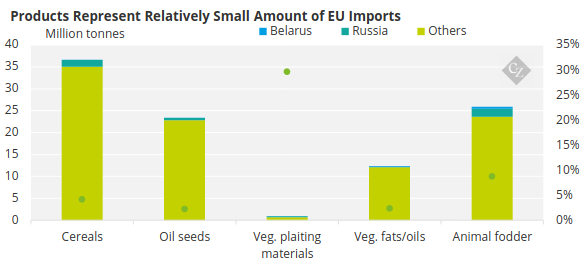

However, the EU says Russian and Belarusian origins account for a small proportion of its total imports of these products.

Source: Eurostat

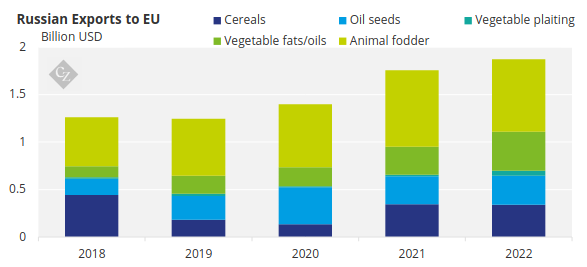

But the value of these products is much greater for Russia – although relatively limited for Belarus. In 2022, Comtrade data shows that Russia exported cereal and oilseed products worth almost UD 2 billion to the EU.

Source: UN Comtrade

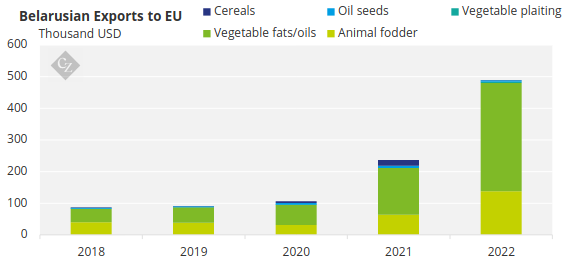

Meanwhile, the value of Belarusian impacted goods was just short of USD 500,000 – although this grew substantially in 2022.

Source: UN Comtrade

How Does This Impact Trade Flows?

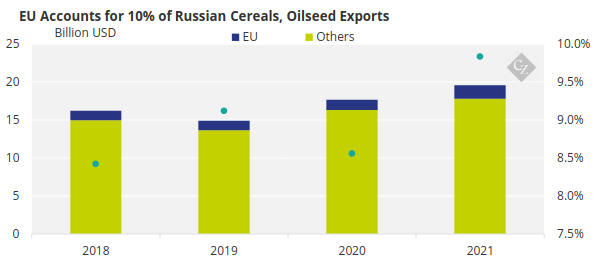

Russia is a major producer and exporter of the impacted products, with about 55 million tonnes exported to the world in the 2020-2022 period. For Russia, the EU accounts for about 10% of all its exports of cereals, oilseeds and derivatives in terms of value.

Source: UN Comtrade

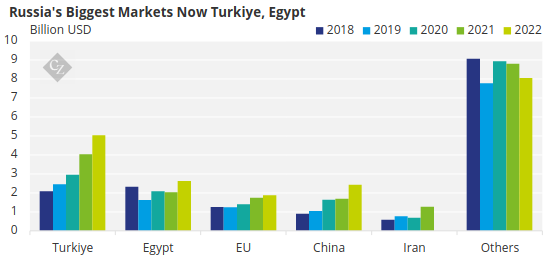

Losing access to the EU market will mean it may have to sell into other regions, possibly at a discount. Aside from the EU, Russia’s biggest markets for these products are Turkiye, Egypt and China.

Source: UN Comtrade

If Russia is forced to sell into other markets more competitively, this could drag the price of these products down across the board, given that Russia accounts for a large volume of global supply.

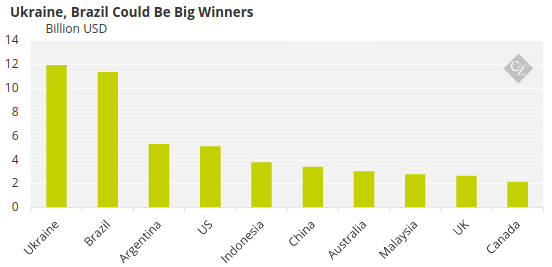

Another question is where the EU will plug its procurement gaps with the loss of Russia and Belarus as suppliers. The opportunity will likely fall to Ukraine or even South American countries such as Brazil and Argentina as they already supply large quantities of the products in question.

Source: UN Comtrade

As freight prices rise though and Ukraine continues to fight a war, the EU may prefer to look closer to home — perhaps to the UK, which is already a large supplier of cereals, animal fats and animal fodder.