- The EU may publish emergency measures related to supply chain disruption.

- Brussels could limit exports to safeguard supply for the common market.

- This might prove disastrous for global supply chains

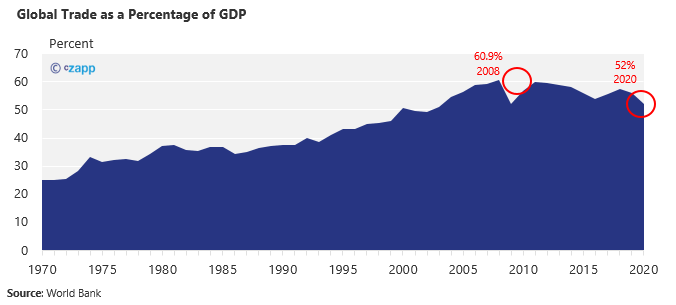

Global supply chain disruptions have pushed the world towards a more regional trade model and away from globalisation. But now, as more and more countries take steps to protect domestic supply of goods, the entire global food supply chain threatens to be knocked off kilter.

EU Moves to Protect Domestic Supply

Last week, reports surfaced of new draft legislation being tabled by the EU that would give the authorities sweeping powers to restrict exports if there were concern over domestic supply. According to the Financial Times, the legislation proposes that the EC should be allowed to override contract law and compel companies to cancel exports under scenarios of low supply.

Under the proposal the EC could also set out a system of “priority rated orders”, which would give them the power to mandate the products produced by each factory and the customers they can sell to.

Global Trade Broadens Product Choice

Many countries exist on a trade deficit. This is because consumers in many developed countries are used to having access to most products all year round.

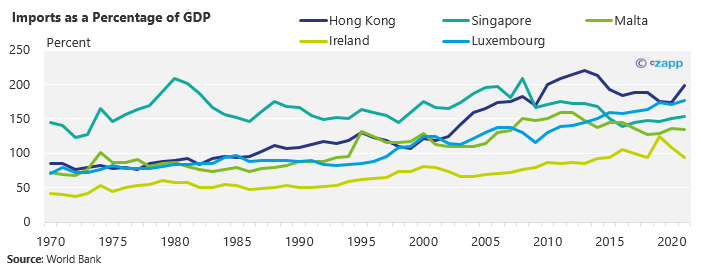

No country wants to be dependent on imports, but this can be necessary in some locations with smaller land mass such as Singapore. Other factors such as climate mean that certain crops are incapable of growing in some countries.

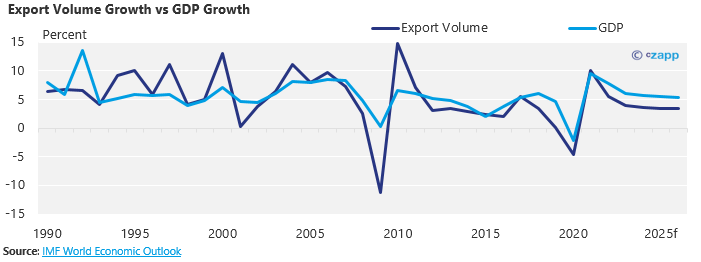

Thanks to global trade, the world can now quickly access perishable, exotic items that may be out of season or hard to grow in their home countries. Global trade is also closely linked with GDP growth.

Not only this, but a global supply chain offers a failsafe. The war in Ukraine is a good example. One of the biggest grain producers in the world, Ukraine has struggled to access international markets since March. But other countries, such as Australia and India, have stepped in to plug some gaps.

Without access to these international markets, it is likely that certain products would be unavailable in grocery stores at certain periods of the year – or at all in certain countries.

Protectionism Will Limit Food Access

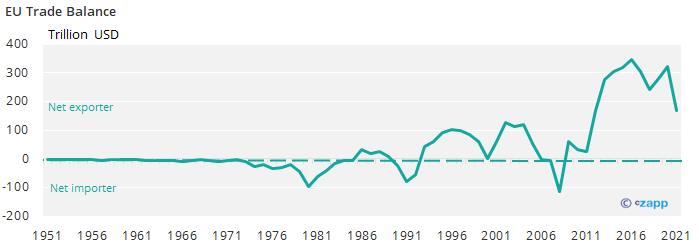

The EU is a net food exporter.

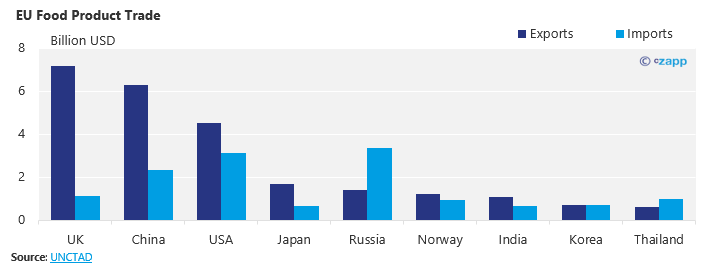

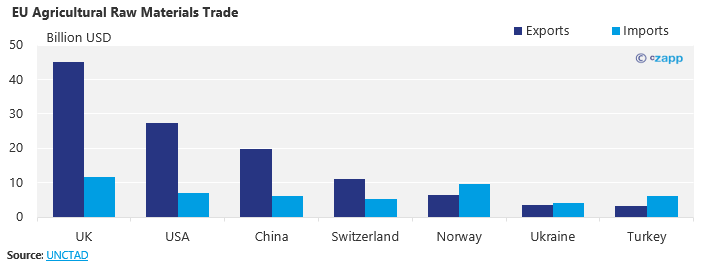

Its main export markets for food products are the UK, China and the USA. These markets also account for a significant amount of the EU’s food imports.

Not only this, but there is also overlap between the EU’s export partners in agricultural raw materials and its main import partners.

EU May Face Retaliatory Measures

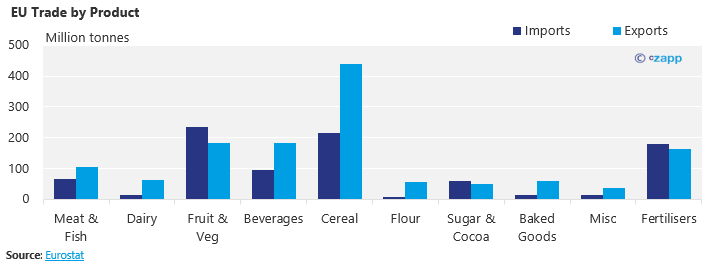

Although the EU is a net exporter, it depends on trade partners for certain products. While the EU generally exports much more than it imports, his is not true for fertilisers.

The EU produces about 64 million tonnes of fertilisers and imports about 179 million tonnes. Given that it exports 161 million tonnes, apparent consumption is over 80 million tonnes – about 16 million tonnes more than domestic production capacity.

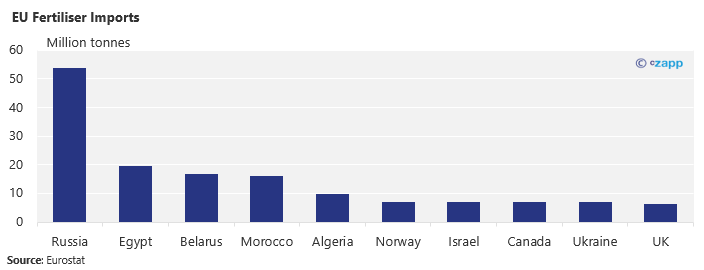

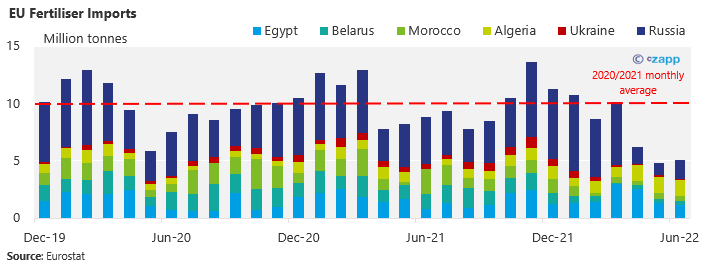

The EU has already suffered supply disruptions to fertiliser supply this year. Russia is its single biggest supplier of fertilisers.

Since the war in Ukraine began, imports of fertilisers from the EU’s major partners have dropped significantly. Sanctions have not targeted food and fertilisers, but the war has generated a host of supply chain ramifications.

If the EU is to limit exports to other countries, it risks retaliatory measures and isolation in an already difficult trade environment. Not only this, but restrictions could create procurement issues and bottlenecks around the world.

Vulnerable Countries Left Out in the Cold

There is the risk that this move will trigger widespread protectionist measures around the world. Already there have been some examples of protectionist measures.

In April, the Indonesian government implemented a short-lived ban on palm oil exports after Ukraine-related disruptions to seed oil supply and high energy prices created shockwaves and pushed up prices.

India has also been toying with a variety of protectionist measures. It imposed controls on the export of sugar and wheat earlier this year, and last week imposed a 20% export duty on certain rice varieties. India is responsible for about 40% of global rice exports and an increase in prices could spell disaster for developing countries.

On the other end of the spectrum, some countries that lack domestic food production capacity are facing the prospect of widescale shortages. This is particularly true for small island countries that tend to have little space for food cultivation.

Singapore in particular struggles with food security. The nation imports over 90% of its food from more that 170 locations, according to the Singapore Food Agency. It has been attempting to roll out various measures to address the issue, including the “30 by 30” program. Through the initiative, it plans to produce 30% of its nutritional needs by 2030.

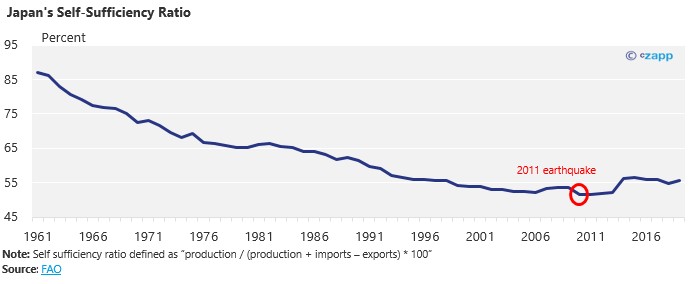

And even developed countries with sizeable GDPs are not immune to the issues. Japan has recently been facing the prospect of having to raise food prices in supermarkets due to rising import costs.

The country’s self-sufficiency ratio has been slowly declining since the 1960s and has dipped below 55% at certain points, such as in the aftermath of the 2011 earthquake that impacted food production.

With increased food protectionism, it seems no country is safe from food supply volatility.

Concluding Thoughts

- Europe’s decision to restrict exports could have serious ramifications.

- Not only will food security be jeopardized, but so too will the bloc’s global standing.

- The EU faces backlash and retaliatory measures from trade partners.

- The move threatens to create a more hostile global trade environment and roll back globalisation.

- This cements a general global trend of fostering regional trade blocs.