Insight Focus

Right-wing parties make gains at expense of Greens and socialists. Larger conservative and nationalist blocs may resist climate ambition. EU ETS seen as safe, but new “ETS2” and 2040 target are vulnerable.

European Parliament Leans Right

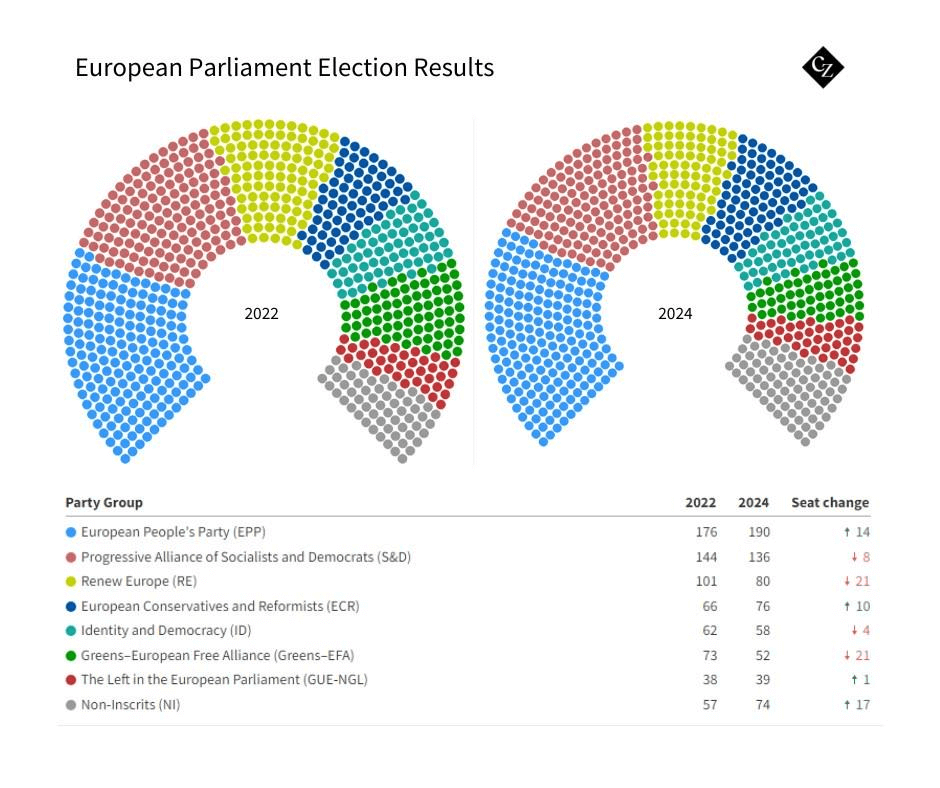

This month’s elections to the European Parliament across 27 countries resulted in a small but tangible shift to the right, with conservative and nationalist groups reaping gains at the expense of socialists and particularly the bloc’s green parties.

The largest group in the 720-member assembly remains the European People’s Party, composed largely of centre-right representatives, with 190 seats – a gain of 14 from the previous election.

The Socialist and Democrat group lost just three members to 136 seats, while Renew Europe, the liberal caucus, lost 22 seats and will now count 80 MEPs.

To the right, the European Conservatives and Reformists will number 76, the Identity and Democracy group 58, while it remains to be seen how 45 non-attached and 44 non-declared MEPs will ally themselves when the new assembly meets for the first time in mid-July.

Opposition May Derail Climate Goals

The rightward shift in the Parliament is not expected to lead to any changes to the EU Emissions Trading System in its present form. After the elements of the EU Green Deal’s Fit for 55 programme that relate to the ETS were successfully legislated in April last year, the market trajectory is now set until 2030.

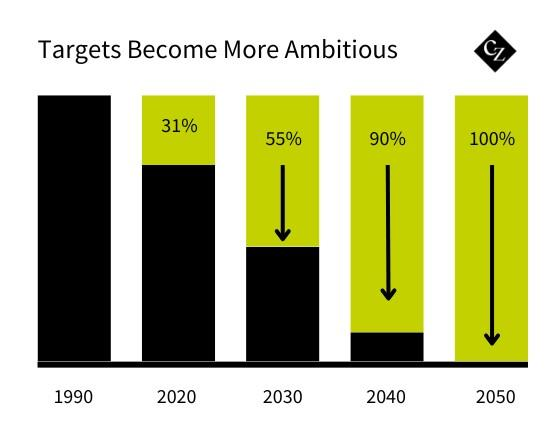

What may be more challenging is the implementation of directives that have yet to be fully operationalised, as well as new policy. Chief among these is the new EU-wide emissions reductions target for 2040, the process for which was launched by the outgoing Commission in February this year.

The Commission has proposed a 90% reduction compared to 1990 levels by 2040. In an impact assessment accompanying the proposal, the bloc’s regulator pointed out that under existing policies alone, the EU would reach an 88% reduction by 2040, implying that the additional effort required might not be too onerous.

Yet those incoming politicians that are fundamentally opposed to more ambitious climate action may nevertheless take the opportunity of the coming debate to decry the EU’s efforts and to resist proposals that would further tighten the EU ETS cap.

ETS2 Under the Spotlight

A more challenging issue may be the debate around the implementation of what’s referred to as “ETS2”. A separate, stand-alone cap-and-trade system covering emissions from fuels used in the domestic and transport sectors, ETS2 represents the closest link between carbon markets and the consumer.

While the new market will cover distributors of oil, gas and coal across the EU, the cost of this new system will most likely be passed on to consumers in the form of higher prices at the pump and steeper gas tariffs. And this will be unpopular with MEPs of all political stripes.

ETS2 in principle is already enacted into law, but the delegated regulations governing its precise operation must be drawn up by the Commission in the coming months. One element of the law offers the opportunity to delay ETS2’s launch by a year if oil and gas prices are too high.

While the Commission itself is responsible for drawing up delegated acts, it must consult with EU representatives and with both the Parliament and Council in doing so. So, there are opportunities to register discontent and opposition and amend the rules.

The main ETS has already impacted consumers through rising electricity prices as a result of the war in Ukraine and the EU’s embargo on the use of Russian natural gas. Adding further increases in gas and petrol prices risks triggering popular protests akin to the “Gilets Jaunes” manifestations in France of a few years ago.

Source: iStock

The European Commission is well aware of this and as part of its ETS2 legislation, it set up a “Social Carbon Fund” that would shield the most vulnerable households from the impacts of the new market. Its challenge will be to persuade the emboldened right wing in the Parliament that these measures will be enough.

There remain many elements of the EU’s Green Deal that must be passed into law – each of these represents a potential flashpoint for the growing opposition to the bloc’s climate ambition to make its case and reverse, or at least slow. the direction of travel.