Insight Focus

Heavy rains this month have delayed the UK harvest and planting. DEFRA’s failure to support farmers could jeopardise food production. Meanwhile, there is cautiously optimism over early-planted crops.

What’s Happening on the Farm?

The most noteworthy event on the farm this month was an emu. Interestingly, an emu can run faster than a whippet—at least when it’s being chased by one. How Cecelia knew she was chasing an emu, I’m not quite sure.

Weatherwise, we’ve transitioned from drought to flood in less than a day.

While we got wet, 80 kilometres to the west, they were washed away, with reports of a third of a year’s rainfall falling in just a week. This will delay harvest and planting in a large part of the English crop-growing areas. We may see a repeat this coming week, though hopefully not as severe. With the rain, we’ve had an enormous flush of grass weeds—more varieties than I realized we could grow!

At the start of the season, we conduct extensive soil investigations, including digging soil profile pits.

It’s always surprising to find roots extending below 70cm (though it’s difficult to photograph). We’ve addressed compaction issues, some more successfully than others, and have completed the usual phosphorus, potassium, magnesium, and other analyses. Manures of various sorts have been applied in compliance with the ever-increasing bureaucratic regulations around application.

After that, we begin preparing the land for the 2025 harvest. We follow a flexible plan that includes both minimum tillage and conventional ploughing. We’re not “purists” in our farming practices—we follow various methods to get the land ready.

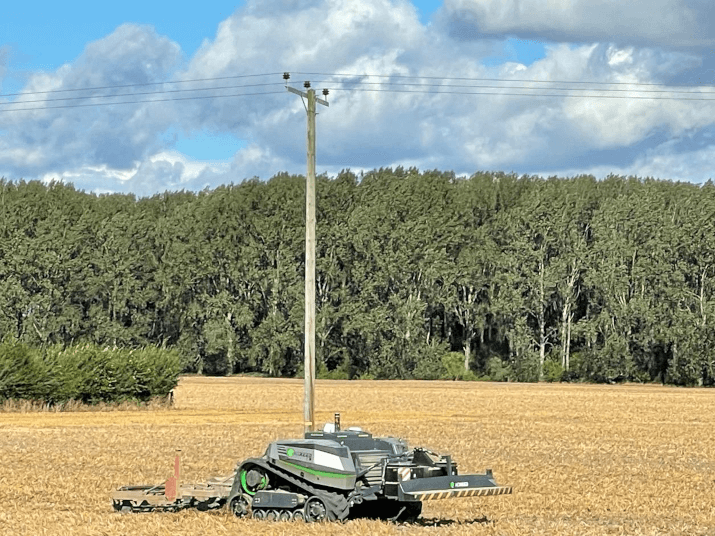

I’m pleased to report that after some helpful discussions with Arthur’s supplier, poles are no longer a challenge.

What Stage are the Crops at?

Wheat/Rye/Spring Barley

Not really a crop stage update, but I read that oat yields in the UK for harvest 2024 have been excellent. Given that oats and spring barley are planted around the same time, I’m still puzzled as to why spring barley yields were so poor. I’ve not yet reached a conclusion.

As an aside, DEFRA recently declared that oats are now a major crop in the UK. Consequently, all grass weed control for oats has been banned—previously allowed for minor crops. The department seems adept at stopping things. This reminds me of comments from fellow farmer Stephen Calcagno, who voiced concerns about the loss of Paraquat.

For the 2025 harvest, we’ve advanced the planting of both rye and wheat by about 14 days.

Research from ADAS, an independent adviser to UK farming, suggests that the higher yields will more than offset the increased input costs. Earlier this year, I visited a wheat field in Northampton where the grower managed the challenges of the 2024 harvest admirably, including 85mm of rain in a single day. We’re following his approach.

We’ve entered ADAS’ yield competition for the 2025 harvest, known as YEN 25. It’s an interesting competition, showcasing the highest farm yields achieved across much of Northern Europe, although it does have a UK bias.

Some of our wheat has already emerged, while other fields are still being planted. Now, we’re on the lookout for slugs.

OSR

Our oilseed rape crop has grown well—perhaps too well. It’s been attacked by the cabbage stem flea beetle, but at this point, all of our plants are still standing. An early fungicide application is due soon, and after that, we’ll be waiting for the pigeons to arrive during the winter. It’s clear why European yield and production have been gradually declining.

Sugar Beet

Currently, yield expectations are higher than last year, as we’ve had a kinder growing season with fewer diseases and pests.

That said, something new will likely crop up. Since August 1, sunlight has been near average, resulting in slightly higher sugar levels than at this time last year. However, the hard ground has made harvesting a challenge. Last Monday, my local factory had 120 tonnes of beet on its pad when it opened for business, and that was with “free loading” throughout the previous week.

If the forecasted rain arrives, sugar levels will drop, but the bulk should increase. However, if it stays wet, as it did last year, we may face harvesting difficulties. With the price drop for the 2025/26 harvest and the possible ban on neonicotinoid insecticides, many farmers may lose interest in growing sugar beet. In a few years, 120 tonnes may be a lot of beets.

What are your Biggest Concerns?

Since last month, DEFRA admitted to failing to distribute GBP 350 million to those on the brink of bankruptcy. The agency claims that around 35% of farmers have signed up for its new schemes, but upon closer examination, it’s mostly the very large and very small farms that have joined. The working farmers have not.

In the broader debate, no one seems to mention that within global agricultural policy, there’s an unspoken agreement that farmers receive subsidies to keep food affordable and widely available. When governments, like the English one, break that agreement, they risk losing their farmers—as we’re seeing now.

And finally, someone should have told Cecelia that whippets chase cats (not emus).