There are a lot of words bandied about on the cocoa market that are very hard to pin down.

The very first ones are cocoa and cacao. Somehow cacao seems more sophisticated than saying cocoa when it comes out of the mouths of chocolate experts. To me, cocoa is just how you say cocoa in English, and cacao is how you say it in French or Spanish. It can apply to the tree, the bean, and even what I would call cocoa powder (i.e. the brown stuff in Milo or in a chocolate cake mix). Rule of thumb: potato potato, tomato, tomato.

Source: Lindt & Spruengli

Then there’s fine flavour cocoa. Bear with me here. “Conventional” cocoa is generally used for bulk cocoa beans that mostly originate in Africa, or are produced in copious quantities that is, thousands of tonnes. The general thinking is that African cocoa is mostly produced from what is known as forastero cocoa varieties (its more complicated that than but that’s for another day), while fine flavour is thought to be from trinitario or criollo (see picture below) varieties. Forastero is supposed to have more of a “chocolatey” flavour while trinitario and criollo have more fruity and floral notes.

The International Cocoa Organization (ICCO) has come up with a working definition of fine flavour cocoa.

Fine cocoa is defined as cocoa that is free of defects in flavour while providing a complex flavour profile that reflects the expertise of the producer and the “terroir,” or sense of the particular environment where the cacao is grown, fermented and dried. Fine cocoa meeting these basic criteria may also offer important genetic diversity, as well as historical and cultural heritage.

Flavour cocoa is defined as cocoa that has little to no defects in flavour and provides valuable aromatic or flavour characteristics that have been traditionally important in blends. Flavour cocoa that meets these basic quality criteria may also offer important genetic diversity, as well as historical and cultural heritage.

The ICCO goes onto list which countries are fine flavour cocoa producers and what percent of their production is fine flavour. For instance, Papua New Guinea is estimated to have 70% fine flavour cocoa as part of their exports. In most cases nobody is working with export agencies to classify each shipment of cocoa. It’s just a guess. In the ICCO’s defence, it’s hard to really pin this down, but if I were a buyer I’d want to know if it’s fine flavour or not.

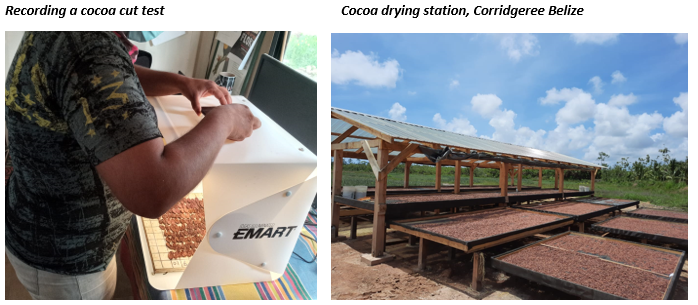

How would I know? Well, I would work closely with partners in the origin country to understand where the cocoa was sourced from using a traceability program and test a series of samples using a quality test (also known as cut tests) and sensory analysis.

The cocoa industry has been slow to come up with international standards of flavour and sensory analysis, although cut tests have been in place for some time and are generally standardized.

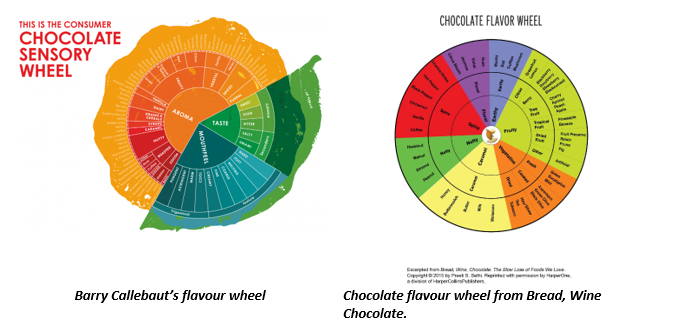

In the meantime, just about every chocolate sensory expert has come up with their own flavour wheel as a way to communicate what they mean by fine flavour. Here are a few examples:

A working group has come up with new flavour and sensory analysis standards which can be found here https://www.cocoaqualitystandards.org/protocols-for-review/download. We have been working at our farm to train our post-harvest team in using these standards, and it has helped us all to speak the same language when we say “fruity,” or “smoky.” Our buyers also know what we mean.

For the conventional or bulk cocoa that is graded and delivered to either London or New York futures exchanges, a cut test is performed by a licensed grader. To gain their licence, graders must be able to distinguish Ivory Coast beans from say, Ghanaian or Ecuadorean beans by examining their physical appearance. However as more grafted cocoa plants start to produce in these origins, and as cocoa beans are more custom fermented it’s going to be difficult to say there is one Ivorian or Ghanaian bean type.

Graders also examine the beans for defects such as mold, insect damage and the presence of slaty beans (which are generally harvested unripe). They also check the size of the beans to make sure they are within specification. But none of this is looking at any of the fine flavour characteristics, they are just making sure the origin on the sample “looks” correct and that it’s within the basic quality specifications so it’s safe to eat, and is discounted or given a premium for any differences in quality from the standard.

Fine flavour buyers are generally doing their own cut tests, but also making liquor samples to check the flavour; why? Well firstly their name is riding on the quality of their chocolate. Most want to tell a story of where their cocoa beans were sourced from, how they were grown, fermented and processed. Then they want to know how to roast and process the chocolate to achieve their preferred flavour expression. Because of things like drought or different fermentation processes, the same cocoa beans sourced this season may

taste quite different to those from their last shipment from the same seller.

Where do I think this is going? I do see a greater decommoditization of the industry, not just because of flavour, but because of label claims like “fully traceable” or Fair Trade, or produced by farmers receiving a Living Income.

You can’t just pick those cocoa beans up on a futures expiry. Buyers need to know what farmers are producing their beans, how they are producing it and where it is at all times in the complex supply chain from a small farm in Nigeria to a chocolate factory in the Netherlands and to the supermarket in Germany. All that costs a lot more than the futures market price plus the standard origin premiums and discounts. The futures market may remain the standard right now but particularly for the fine flavour market, its usefulness as a price discovery mechanism is limited.

Source: Green & Black’s

I imagine there are a lot of interesting meetings happening at the large chocolate manufacturers as they look at the hedge effectiveness of the futures market as this decommoditization gathers pace. Hedge effectiveness examines the relationship between the futures price, and the final price paid for the commodity delivered to the factory door, which includes all the premiums for traceability, farmer price incentives, program costs to train farmers plus all the usual origin differentials. Once the final price and the futures price diverge too much, then using futures for your risk management strategy is deemed ineffective and its game over, or you call in the creative accountants. Next time we will dig deeper into the cocoa varieties I spoke about earlier. As with everything in cocoa, it’s complicated.