Opinion Focus

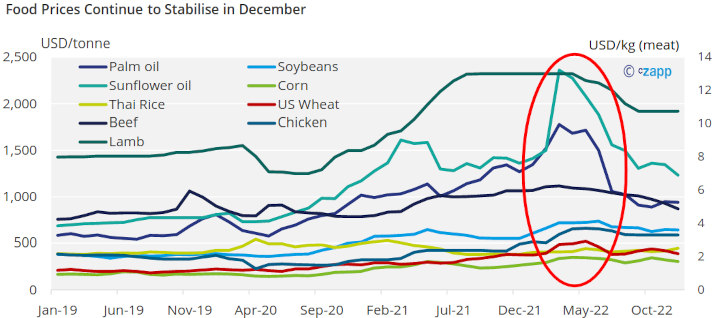

- Prices of food commodities have dropped since highs at the beginning of 2022.

- But levels still remain elevated compared with 2019

- Issues such as pests and lack of fertilisers can still have a significant impact.

The global supply chain has been plagued by news of high demand, problematic supply and overall rising costs in the past year. But as the tables seem to turn, Czapp takes a look at the factors easing food price inflation and the potential risk factors that may still push prices up again in 2023.

Food Prices Drop

At the beginning of 2022, there was a significant bump in the prices of many food commodities. Several factors including supply issues and the war in Ukraine added to inflationary pressures to force prices upwards.

Source: UN Comtrade

Now, as supply chains begin to untangle, food prices are coming down again, but they still remain above pre-pandemic levels. There are some positive and negative factors feeding this trend.

War Impact Limited

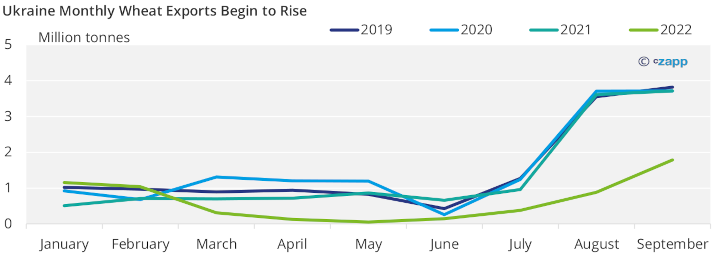

After the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February, the global community was concerned about the availability of wheat. Known as the global breadbasket, Ukraine was the fifth largest grains exporter globally, while Russia was first.

Ukrainian exports ground to a halt as the war ramped up in May, driving wheat to its highest price of USD 522.29/mt. But as grain corridors were established, export numbers rose and the price of wheat dropped.

Source: UN Comtrade

Interestingly, even though Ukrainian grain exports have not recovered to pre-war levels, the price of wheat in December 2022 was USD 386/mt, just USD 10/mt above December 2021 levels.

The war was expected to have some indirect impacts due to concerns over food supply. In the immediate aftermath of the invasion, the threat of protectionism hovered over the global supply chain.

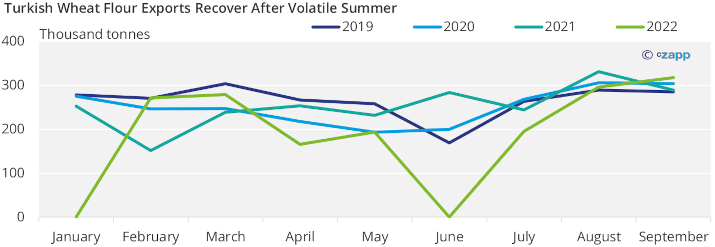

Both Romania and Hungary announced a ban on wheat exports, while the Turkish Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry added wheat products to its list of items eligible for export regulation. Turkish wheat flour is important for global food security as much is exported to lower-income countries such as Yemen, Lebanon and Syria.

Source: UN Comtrade

But after a dip in the summer, Turkish wheat flour exports have remained relatively stable, indicating that fears of protectionism never materialised and helping to calm food inflation.

Dropping Demand Calms Inflation

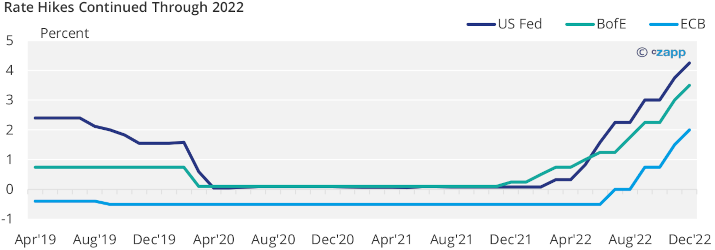

After a year of lockdowns globally in 2020, 2021 was the year when normality resumed for most of the world. Pent up demand created a flurry of buying activity, especially since money was being pumped into the economy by governments all around the world.

But this artificial stimulation of the economy had to end, and as predicted it ended in interest rate hikes from many central banks in an attempt to tame inflation.

Source: US Federal Reserve, European Central Bank, Bank of England

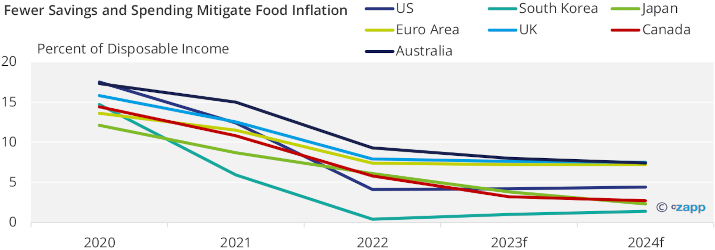

Now, as rate hikes take effect, consumers are buying less, which is helping to mitigate food inflation. In 2022, household savings as a percentage of disposable income dropped substantially from 2020 across many developed countries and regions.

Source: OECD

There is also no huge wave of demand from China yet after the government began its reopening plan. The fact that demand is still weak is a positive in that it helps to temper inflation.

Weather Calm So Far, But Clouds Gathering

The weather outlook in 2023 is a mixed one. While this is likely to be the first in several years in the Pacific without a La Nina event, adverse weather became much more common in 2022. From heatwaves and wildfires across Europe to devastating flooding in Pakistan, crops around the world felt the effects.

As 2023 begins, the weather is largely calm but global climates are changing, meaning global crop growing patterns will be impacted. This has the potential to push up the cost of food again.

Pests, Viruses Still Loom Large

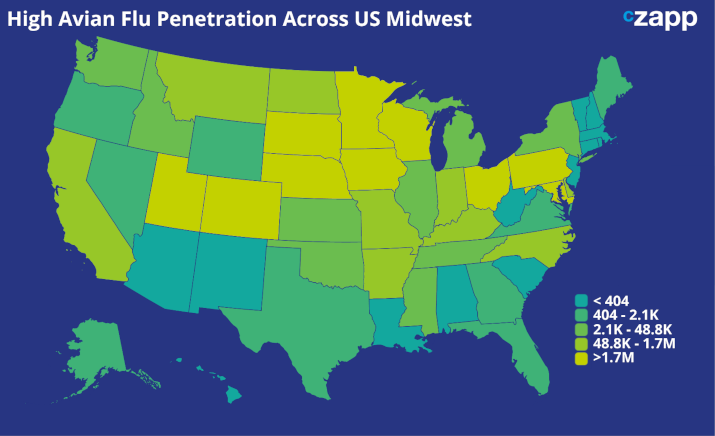

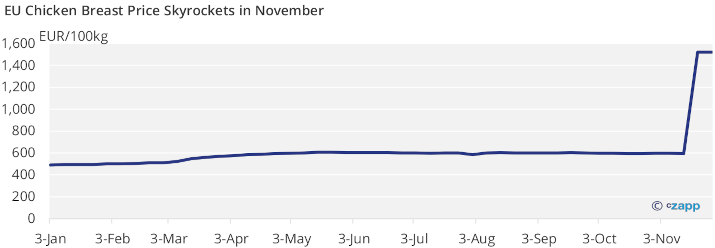

Another negative factor for food prices that will continue into 2023 is the increasing prevalence of pest and pandemic across the animal world. The global poultry industry battled the worst avian flu since records began in 2022.

Without the promise of a vaccine, there is a good chance that the price of meat, and chicken and eggs in particular, will rise again in 2023.

Source: European Commission Agridata

Energy, Fertilisers Remain Elevated

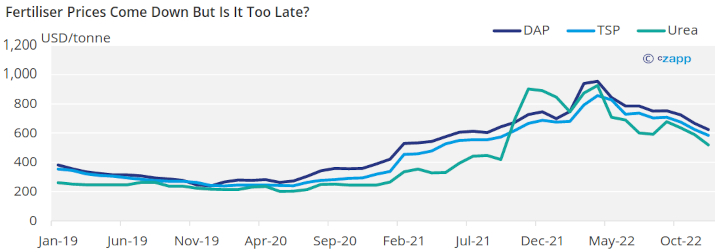

Fertiliser prices have been falling for the past few months, but they still have not quite gotten back to 2020 levels. Although these are now much more affordable for farmers, the real question is the damage that has been done to the next crop as fertiliser application became much scarcer.

Source: UN Comtrade

Application of less, lower grade fertiliser means nutrients will be lacking, and harvests in 2023 could be much smaller than their predecessors. This would push food prices up.

But the good news is that pressure on energy prices will ease as European spring approaches. This should push down fertiliser costs, giving farmers the opportunity to regain some ground.

Concluding Thoughts

- Food prices have been falling after a massive increase in 2022.

- Ukraine’s ability to export wheat and the lack of real protectionism are helping to stabilise prices.

- The rise in interest rates is also calming consumer demand – another factor in lowering prices.

- But some wild card events such as weather and animal flu may throw a spanner in the works.

- Harvests could suffer due to lack of fertiliser in 2022, which in turn would push prices up again.