Insight Focus

- COVID, Ukraine-related food insecurity sparks import deregulation.

- Regulatory changes impact food quality and have environmental ramifications.

- Could damage from lower standards outweigh benefits?

COVID-19 and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have thrust food security into the spotlight. Ensuring food supply is one of the most important jobs a government has. To protect supply, nations are dropping their standards, less concerned about things like fungus contamination, genetically modified organisms and pesticide use so long as it means there’s food on the table. With some of these changes demanding amendments to legislation, permanent alteration of standards looks likely.

Food systems and security have been stretched to the limits in recent years.

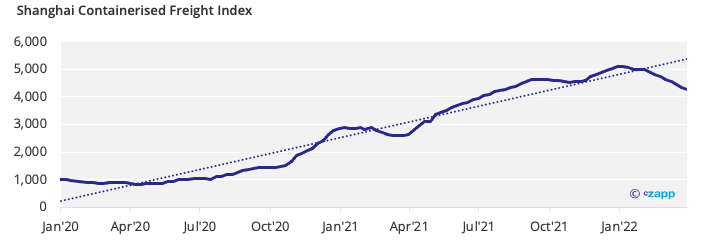

COVID disrupted the entire supply chain and exposed the risks of “just in time” distribution networks. Port closures, container shortages and surging freight rates sparked issues that are still having an impact even as large parts of the world return to normal.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has also hit global food supply, as the pair are the first- and fifth-largest grains exporters respectively. Russia being one of the world’s largest fertiliser producers has also threatened yields in many nations, with supply off the table.

There are no quick fixes to a problem of this scale, but our recent work on Egyptian wheat and Brazilian and US fertiliser shed light on some solutions.

Another way in which nations can boost food supply is by lowering standards. Food standards have massively improved in recent decades but the good work could be undone now the world faces a food crisis. Here’s what we’re seeing already:

The Walls on Wheat Imports are Coming Down

With Black Sea wheat off the table following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, several countries are scrambling for alternative supply. The issue is particularly pronounced in North Africa, where Egypt, the world’s largest wheat importer, is now turning to India.

India’s wheat exports have been limited in the past with importers concerned about bunt, a fungal disease the crop is known to carry. Iran banned Indian wheat imports in 1996, in case the disease spread onto local crops, and flows to Egypt have always been low due to laws surrounding fungus and fears over quality.

Egypt is not the only country now turning to India for wheat, though. Kenyan millers are hoping the import ban is lifted to alleviate supply issues.

China has also altered its wheat import policy so it can accept previously banned supply. It’s also agreed to lift restrictions on Russian wheat, which previously limited trade due to concerns surrounding bunt.

What seems like a quick fix now, though, could create long-term problems if disease spreads to local crops. Such transmission could destroy crops or impact yields for years to come.

Genetically Modified Foods Push into the Market

Genetically modified (GM) foods are controversial, with some campaigners worried about the adverse impacts they might have on health. Experts also fear that GM crops could jump into the natural world and become unwieldy invasive species, harming biodiversity.

With food insecurity increasingly a concern for nations, though, some are relaxing or debating relaxation of laws that limit GM imports. Russia’s fertiliser export ban and today’s high fertiliser costs have also heightened global interest in GM crops, which require less input.

The EU, for instance, has historically had some of the strictest laws governing GMOs. However, some member states, including Spain, have recently altered certain laws to boost food security and are thinking about changing others that govern GM usage. The European Commission has also authorised the import of specific soybean, oilseed, and cotton crops.

With this, EU farmers are turning to US and Brazilian corn for animal feed in place of Ukrainian supply. Ukraine accounted for more than half of the EU’s corn imports in the last five years as most US and Brazilian corn is genetically modified.

Beyond the EU, Egypt is now looking to lift restrictions surrounding GM crop production in attempt to reduce import reliance. It previously allowed the import of some GM products but had strict laws around domestic GM production.

Elsewhere in Africa, officials from Nigeria’s National Biotechnology Development Agency are keen to embrace GMOs to boost self-sufficiency.

China has also issued legislation to increase GMO consumption, as have the UK and parts of Australia. Some of these calls pre-date the Russian invasion but have intensified since.

Any changes to boost GMO consumption shouldn’t instantly reverse when the crisis abates, especially if they are popular with farmers and can help boost self-sufficiency. GM crops demand less input (notably pesticide and fertiliser) and are also higher yielding. Will these benefits be too good to let go?

Herbicide, Pesticide and Fertiliser Laws Relaxed

France and Spain have tightly governed the import of animal feed that contains traces of herbicide and pesticide in the past. However, these nations are now looking to alter these laws, enabling them to find alternatives to Ukrainian corn.

The crisis has seen several nations, principally France, push back against the EU’s Farm to Fork strategy, which looked to cut chemical fertiliser and pesticide applications by a half and third, respectively. Slovenia and Poland have asked for more malleable targets, and other nations across the EU appear more opposed to the strategy now food insecurity is more of a threat.

What Does This Mean?

These examples show that standards centred around sustainability and quality are taking the back seat as food insecurity becomes more of a threat. This isn’t surprising; reducing standards to make sure people don’t go hungry makes sense.

These short-term changes could have long-term impacts, though. Fungal contamination and problems with invasive GM species, for instance, don’t come with overnight fixes. And once governments start to unpick legislation, it may not be so easy to implement again.

Alterations of standards made during a crisis could shape food regulation for years to come.

Other Insights That May Be of Interest…

Czapp’s Sugar Consumption Case Studies

Explainers That May Be of Interest…