Opinion Focus

- France is a major grains exporter and a strategic supplier to North Africa.

- After a low crop in 2020/21, adverse weather is threatening the next crop.

- This gives the EU a further incentive to try to open up Ukrainian ports for grain exports.

The world is facing a grains supply crisis. One of the world’s largest producers, Ukraine, is only able to export a fraction of its grains due to the Russian blockade of its Black Sea ports. Now, one of the best back-up supplies is facing issues as hot weather in France threatens its winter grains crop. If more grains cannot be exported from Ukraine, the world will continue to face grains shortages and price rises, with the poorest countries paying the highest price.

France Produces 20% of European Grains

France produces about 57 million tonnes of the world’s grains. Of total EU production, it supplies about 20%, primarily exporting to nearby North Africa.

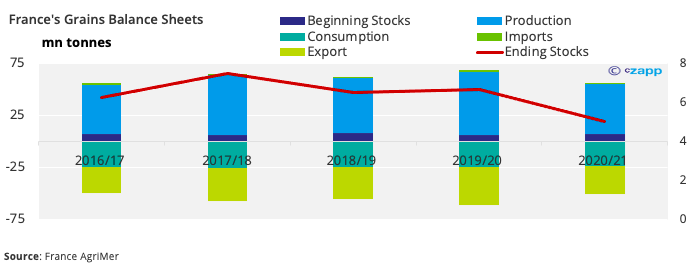

In 2020, France had a very poor crop, meaning that at the end of 2021, grains stocks were fairly low.

This would normally not be much of a problem. Although not a major importer, France has been able to be flexible with exports to ensure domestic grains supply is sufficient.

Drought Threat Jeopardises Winter Cereals

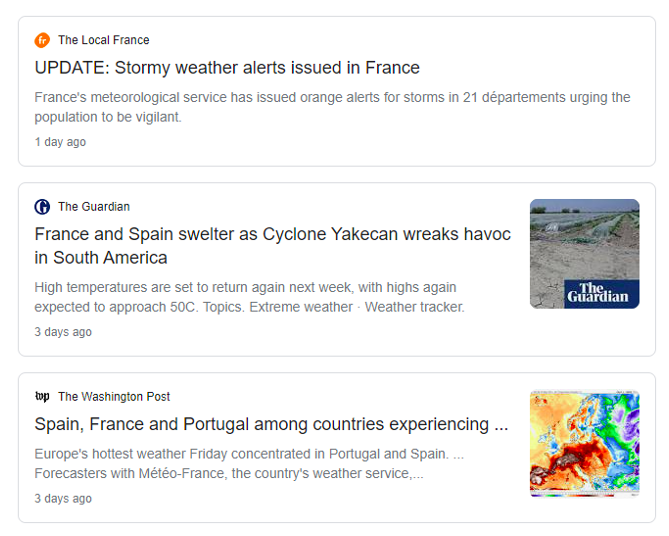

This month, the French Ministry of Ecological Transition published a map showing a high risk of water shortage this summer. The regions most affected are around Nantes in the west and Marseille in the southeast but 76 areas have been classified as high alert, 26 of which are very high alert.

A lack of rainfall from about September to February has meant the groundwater has failed to replenish, meaning it remains particularly low in many regions and threatens to create extremely dry soil this summer.

In addition, the country has been experiencing hotter-than-normal temperatures over April and May. It is “highly likely” that May will be the hottest on record since World War II, according to the French weather service.

Wheat ratings are now declining, generating concern about yields for the 2022/23 harvest. The French Ministry of Agriculture said agriculture has been given priority status for water supplies during the crisis.

Situation Heaps Pressure on Global Supply

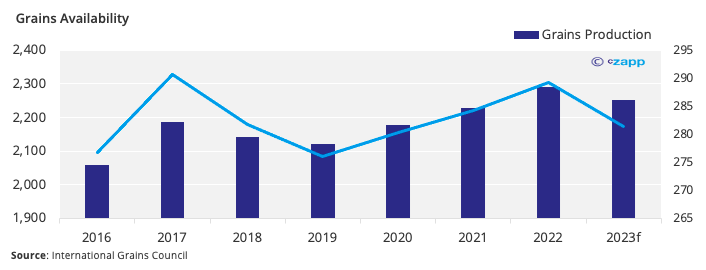

South Europe’s drought could not have come at a worse time for global grains supply. The International Grains Council on Thursday cut its outlook for world wheat production to 769 million tonnes, a three-year low.

Meanwhile, the population is growing, meaning that grains availability on a per capita basis is dropping sharply.

This is in turn piling pressure on other countries, who are turning to more nationalist approaches to ensure domestic food supply.

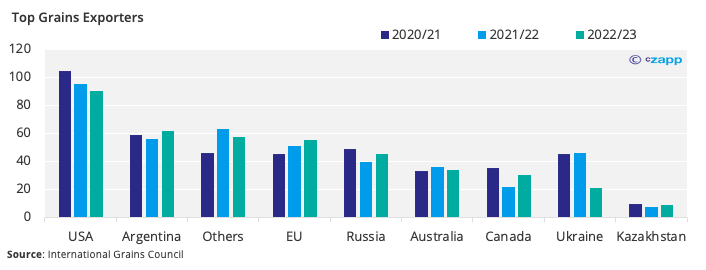

Argentina, the world’s second largest grains exporter after the US, said it planned to set up a price control mechanism for domestic wheat prices that would help mitigate inflation.

The EU as a bloc is the world’s third-largest exporter of grains. Some countries, including Hungary, Bulgaria and non-EU Serbia, have taken steps to secure grains supply. Hungary took the blanket approach of banning all grain exports, while Serbia imposed restrictions on wheat, corn, flour and cooking oil exports. Bulgaria floated the idea of a potential export ban on grains.

Ukraine and Russia, which collectively export about 65 million tonnes of grains each year, have been crippled by the war. Even before the war in Ukraine, Russia had already imposed taxes on grain exports. And while Ukraine is still able to continue producing grain, exporting has become an incredibly complex issue given that it has been cut off from Black Sea seaports.

Recently, tensions have been felt in the Middle East. Prices have risen to record levels and governments are trying to contend with procurement challenges. Egypt imported a massive 5.5m tonnes of grain from Ukraine in 2021, accounting for almost 25% of Egypt’s total grain imports. Now, the government must find an alternative supplier or risk political upheaval.

Risk of Food Protectionism Rises

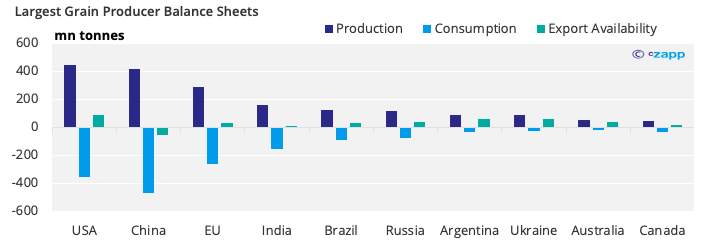

So, what other options are there? Of the top 10 grains producers, there is very little export capacity when taking into account their domestic consumption. While in the US, grains production is forecast to reach 443.9 million tonnes this year, consumption is also high at 355.6 million tonnes. And despite China’s mammoth, 418-million-tonne production, it still has to import to meet domestic needs.

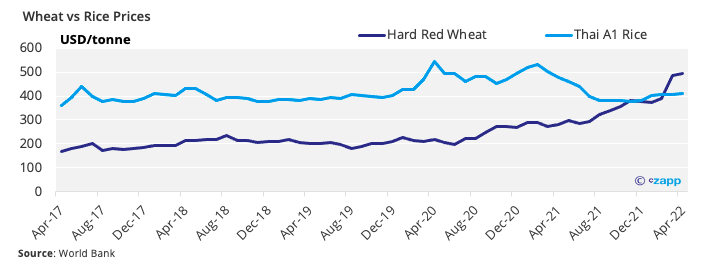

The UAE has recently been encouraging a switch to rice-based staples instead of wheat-based staples given that rice is still readily available and is now cheaper than wheat. In African countries such as Kenya, Egypt and Nigeria, people are mixing cheaper alternatives into bread, pastries and pasta.

India, a country with a large surplus of wheat, recently banned export of the staple, causing international prices to skyrocket. But the ban is not wholesale, with the government stating that it will allow exports backed by already-issued letters of credits, those already registered in the customs system as well as exports to countries “to meet their food security needs”.

India is largely seen as a favourable option to shore up Middle Eastern wheat supply given its huge stockpiles, proximity to the region and relatively low prices.

Concluding Thoughts

- The risk of increased food nationalism and the threat to globalisation is growing.

- The world grains situation is in a precarious position.

- We should expect constrained supply and further price rises.

- Countries with stockpiles will have an opportunity to take advantage of the situation.

- India must make the choice between bowing to food nationalism and taking advantage of higher grains prices.

- This will heap further pressure on Middle Eastern and North African countries.

- The Western authorities are likely to push more resources into getting grain out of Ukraine.

Other Insights that may be of interest

What the Energy Crisis Means for Inflation & Commodities

Interactive Data Reports that may be of interest …

Consecana Panel

CS Brazil Weather Update