Insight Focus

- Markets have responded to disruption to Black Sea grains shipments.

- Energy security is an overlooked part of food security.

- The commodity trade can use its influence to enhance sustainable food security.

Introduction

Food security requires four aspects are met. You need to:

- Grow, make and ship enough food.

- Make it cheap enough that everyone can buy what they need.

- Ensure both sufficient energy and nutrient intake.

- Ensure these three factors are stable through time.

Food security has been in the news a lot so far this decade. 2020’s COVID lockdowns, 2021’s supply chain problems, 2022’s Russian invasion of Ukraine and 2023’s food price inflation have brought the subject to everyone’s attention. How can we try to ensure 2024 and the years that follow are better?

I spoke on a panel about food security at the TXF Global Commodity Finance and Sustainable Natural Resources Conference in Amsterdam on 23rd May. The original plan was that the panel would discuss the effects of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on global food supply. However, the flow of grains from the Black Sea has become a little more normal than it was 12 months ago, so instead the panel focused on how we feed a growing population while also decarbonizing food supply chains and enhancing sustainability and traceability.

Mid-Flow at the TXF Conference, May 2023

These are wide-ranging subjects and so here are some loosely connected thoughts on food security which I covered at the event.

Solving Black Sea Grains Shipment Disruption

On 24th February 2022, Russia invaded northern, eastern and south-eastern Ukraine. Ukraine mined the approaches to its ports, while the Russian navy announced a maritime exclusion zone, blocking access to Ukraine. Commercial sea traffic therefore stopped, stranding grains destined for export within Ukraine. The USDA estimates as much as $1.6b unsold grains were left in stock.

Ukraine is a major food producer and exporter. Pre-invasion it accounted for 14% of the world’s corn supply and 10% of the world’s wheat supply. Grains prices promptly spiked higher. CBOT wheat rallied from $8/bsh pre-invasion to a high of more than $13/bsh on 7th March 2022. CBOT corn moved from $6.50/bsh to a high of more than $8.20/bsh on 29th April.

Source: Refinitiv Eikon

This was clearly a major food security event, especially for nations reliant on grain imports.

Source: Refinitiv Eikon

On 22nd July 2022 Russia and Ukraine agreed to allow safe passage of grain exports from Chornomorsk, Odesa and Yuzhny/Pivdennyi ports. Since this time, vessels have been allowed to proceed through narrow corridors from the ports to a staging area, and then steam south towards the Bosphorus. 30m tonnes of foods have been exported, around half of which is corn. This represents a flow of around 3m tonnes a month, around half what Ukraine used to export before the invasion.

Russia has made periodic threats to withdraw from the agreement, but it still stands. Turkey was a leading broker of the agreement and is also now Russia’s third largest trading partner. Turkish exports to Russia grew from USD 5.8b in 2021 to USD 9.3b in 2022 as many other western countries reduced their business activities.

Russia is also increasingly dependent on its ally China for support. But China is not self-sufficient in food and is the world’s largest importer of grains, primarily from the Americas. China does not want prolonged high grains prices and may guide its ally accordingly.

The main problem with the Black Sea region now is around crop production, not supply. Large parts of East and South Ukraine remain occupied, reports suggest farm infrastructure and agricultural machinery across the occupied regions have been destroyed. Up to 470k ha may require demining once the conflict ends.

The USDA believes crop area has fallen by 20% in 2023. They have also observed a reduction in corn seed imports, hinting that farmers might be switching to other crops that can be more easily sold domestically.

Nevertheless, corn and wheat futures prices continue to fall and are now back at 2021 levels. Perhaps one lesson from this grim saga is that markets can adapt relatively quickly to disruption. The main question is whether the adaptation process is an easy one. After all, food security isn’t just about availability and affordability. The fourth aspect I showed at the start of this article demonstrates the importance of time. Can people cope with higher prices and supply disruption for a period of time?

In the case of Black Sea exports, the grains corridors were opened after several months. But the downstream effects are still being felt today. For example, food price inflation in the UK right now is somewhere between 10-20%. This is a major problem for the British government, which is trying to keep public sector pay deals close to 5%. People’s food security is getting worse.

Beyond price, there are also problems with availability. The spread of Avian Flu has led to egg shortages, decades of poor energy policy has led to tomato, pepper and cucumber shortages (see next section). In isolation all these things are unfortunate. Put together and the possibility of regime change is real; not through a coup, but at the next general election in 2024 or 2025.

With this in mind, how can governments and consumers ride out supply disruption? The obvious answer is to hold higher stocks of food. But holding stocks can be expensive and so companies and consumers have become used to holding less stock through time. Decades of falling food prices have incentivized procurement managers to buy late, so securing better prices. Shoppers in the UK and elsewhere have become more accustomed to reducing the size of the weekly food shop in favor of buying fresh ingredients when needed (or indeed summoning prepared food on demand through apps).

An alternative approach is to build more redundancy into supply chains.

This can be as simple as being aware of which ingredients and foods can be easily interchanged: switching from sunflower oil to rapeseed oil, for example. But it can also mean not relying on a single supplier or trade route.

Working with a company like Cz can help because we can help you to adapt. In the past few years we’ve helped many customers respond to higher prices and snarled supply chains. During the container shortages of 2021 we helped multiple customers in close proximity aggregate their goods to be able to ship them by breakbulk. Where we couldn’t aggregate one product, we looked to co-ship multiple goods for buyers in one vessel.

Energy Security is Food Security

Russia’s invasion also highlighted how interconnected the world is. Food security is as much about energy security as it is about moving goods. After all, it takes energy to run farm machinery, make fertilizer and operate food and beverage factories. Without a cheap and stable energy supply it’s hard to manage efficient truck, rail, sea or air supply chains.

The journalist Ed Conway has a stark example of how 2022’s high energy prices hit the UK’s food security. He’s revealed how decades of poor energy policy meant the country ran out of tomatoes, peppers and cucumbers in February 2022.

Most salad vegetables in the UK are grown in large greenhouses. It takes energy to heat these greenhouses, to ensure optimum light and humidity and to pipe carbon dioxide in to promote photosynthesis. In the UK much of this energy comes from natural gas.

A Vegetable Greenhouse in the UK (Measuring 300mx300m)

For years natural gas prices in the UK have been low. We had North Sea supplies, then Europe had cheap Russian supply. The European natural gas price through the 2010s was between 10-30 Euros per megawatt hour. Politicians assumed natural gas was natural gas – the same molecule at the same price whether it came from the North Sea, Russia or Qatar. It could all be delivered cheaply on a just-in-time basis. Indeed, the UK shut 70% of its gas storage in 2017. The government thought it was too expensive to operate.

EU TTF Natural Gas Prices Spiked In 2022

Source: Refinitiv Eikon

Then global demand for energy increased as we learned to live with COVID. Prices increased. In 2022 Russia invaded Ukraine, gas flows to Europe stopped and prices went through the roof, peaking at 10 times the 2010s range. Although energy prices rose, UK supermarkets refused to offer UK greenhouse operators higher prices for their crops, and so farmers chose not to grow salad vegetables. Imports were then hit by bad weather and there were no tomatoes in the shops.

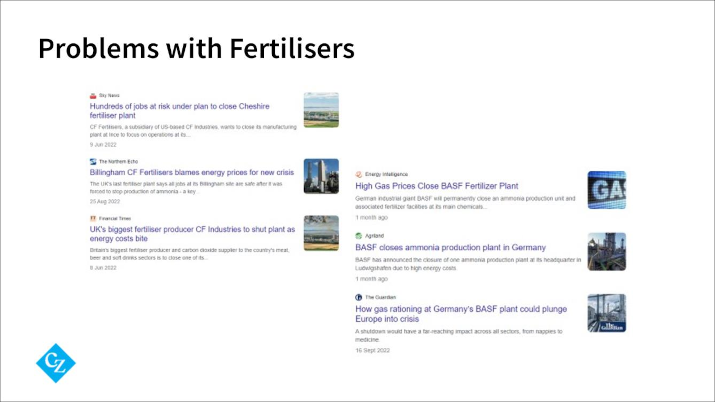

Another fine example of the interconnectedness of food and energy came about in the fertilizer market.

Making fertilizer is extremely energy intensive, especially nitrogen-based fertilizer. To convert nitrogen to ammonia requires high temperature and pressure and metal catalysts. Globally this accounts for around 2% of energy consumption and 3% of the world’s carbon emissions.

EU Fertilizer Plants Shut in Response to High Energy Prices

As European natural gas prices rose, fertilizer plants started to shut down. However, carbon dioxide is a by-product of ammonia synthesis, and so European carbon dioxide supplies started to decline. Fertilizer plants make around 60% of UK carbon dioxide supply, for example.

As well as being used to carbonate soft drinks, carbon dioxide is used to stun animals at abattoirs ahead of slaughter.

So the UK’s poor energy policy ultimately led to shortages of salad vegetables, meat and soda.

Although European natural gas prices are now back in their pre-2020s levels, this is not the time to become complacent about food security.

Natural gas prices used to be regionalized. Gas could only be moved long-distance by pipeline. Today liquified natural gas means that there is a more effective world market price.

The EU TTF price no longer just reflects supply from North Sea gas fields, nor supply from Russian pipelines. In the past winter it’s shown the price of LNG cargoes arriving from the US or from Qatar. Europe competes with China, Japan, Korea, Pakistan, Egypt and many others for these cargoes.

It’s time we recognized the importance of cheap energy for food security. A government can’t last if it can’t feed its people. Perhaps the UK’s ruling conservative party has finally realized this, 18 months before the next general election? The UK in the last week has held a food security summit, hosted by the Prime Minister. While there were plenty of representatives from across the farming and food supply sector, no-one seems to have mentioned the importance of cheap and reliable energy. I therefore fear the summit will have been ineffective.

Using Sustainability to Promote Food Security

For much of human history, agriculture and food security have been local. Food was grown and stored near where it was consumed.

Today, food supply chains are globalized. The food sector can be highly fragmented, with millions of farmers and processors feeding billions of people across the planet. The world’s population continues to grow. Feeding 9b people by 2050 while decarbonizing supply chains remains a major food security challenge.

In addition, governments and consumers increasingly require greater transparency in food supply chains: more traceability and greater sustainability of food.

However, food and beverage companies sometimes struggle to drive change across complex globalized food supply chains. A candy bar eaten in Oman might contain refined sugar which was imported from a refinery in Dubai which itself imported the raw sugar from Brazil.

Commodity supply chain companies can therefore help improve food sustainability and traceability. They have a deep commercial understanding of their networks and so know where to target their efforts for maximum benefit.

Another benefit of commodity companies driving sustainable practices across their supply chains is that they have a powerful brand. This means they have an incentive to impose quality onto their supply chains. Ultimately, they can add value to a product which is otherwise commodified, like sugar.

The advertising guru Rory Sutherland has written extensively about the importance of brands in driving higher standards. He mentions that without a brand or identity it’s difficult to differentiate between goods and so the company that offers the lowest cost wins. There’s an incentive to cut corners to lower costs. After all, why bother making something better if no-one knows you did it and any fallout is shared equally among your competitors?

One example he gives is about rivet production in the Soviet Union. Factories were given a monthly quota of rivets to manufacture. The unbranded rivets were sent to a central depository where they were mingled with all the other factories’ rivets. The now indistinguishable rivets would then be shipped to where they were needed. But without the maker’s name on the product, the quality of the product fell even as the quantity rose. The regime eventually made the factories stamp their names on the rivets and quality was restored.

Brands therefore signal a quality product and a positive intent. Trade houses can use their position in the supply chain and the power of their brand to demand better sustainability and traceability in their supply chains.

This is what we do at CZ.

The VIVE Sustainable Supply Programme uses our unique position in the supply chain to stimulate supply flows that meet high, verified standards. We are working for the long term, with VIVE participants committing to continuous improvement.

We now have 23 participants in 14 countries and in 2022 1m tonnes of product moved in our systems as VIVE. More than 80 buyers of food, ingredients and packaging now support VIVE.

We successfully verified the first ever end-to-end shipment of sustainable sugar in 2020, and we are now applying these learnings to other product areas – to increase the available supply of recycled polyethylene terephthalate (‘rPET’), for example. In 2022, we increased volumes of biomass and solar-produced energy and we piloted a new VIVE Climate Action initiative.

We strive to bring down the cost of sustainably-sourced products by working with supply chain participants on the ground to reduce their impacts on the planet and to improve their social and governance practices. These actions make their products more commercially viable for industrial end users.

VIVE has long-standing relationships with Rabobank and OCBC Bank and these partners can reward VIVE participants with discounted finance rates subject to commitment and performance. In 2022, we laid the groundwork to add a sustainability linked loan to our borrowing base, which we will launch during 2023. This will increase the availability of green capital and liquidity for activities associated with VIVE.

By committing to continuous improvement in ingredient supply chains, we develop strong relationships with our VIVE participants to create significant commercial advantage through increased volumes, longer-term contracts and new partnerships. By interacting with VIVE participants ‘on the ground’, CZ can directly improve processes, procedures and the commercial viability of products. These actions benefit people’s livelihoods and welfare, as well as their local communities, through improved standards and reinvestment.

We can act to make a better and more robust food supply chain, helping to enhance food security in the years to come.

If you’d like more information on how VIVE can help your business, please contact Ben French.