Opinion Focus

- Food producers are coming up with new ways to cut costs as inflation bites.

- A range of measures, if implemented correctly, could mitigate the impact on markets.

- However, if applied long term, these measures could put food supply at risk.

With the world facing unprecedented supply-chain issues, food producers need to take steps to ramp up production with increased yields. But record high costs threaten to derail food production as fertiliser and energy prices continue to surge. Food producers are addressing issues in a variety of ways, but some of these could have long-lasting impacts on food security.

Rising Energy Costs Create Renewable Opportunities

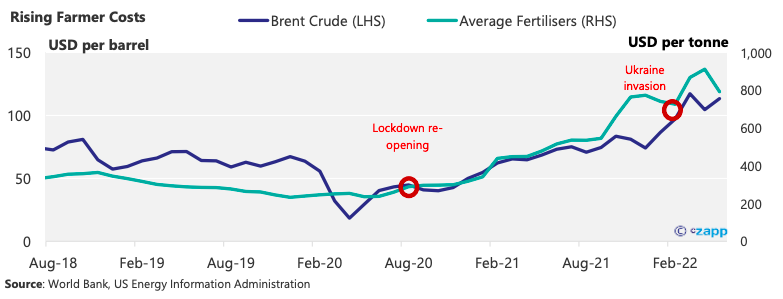

For farmers, the cost of inputs has risen substantially in the past year. In the past few months, the price of oil has reached highs last hit in 2014, while fertiliser prices have soared to an almost 15-year high.

For energy-intensive agriculture such as dairy farming, annual energy bills can reach into the hundreds of thousands of dollars, and these have only escalated in the past year as energy prices have ballooned.

This has prompted more farmers to turn to on-farm sources of renewable energy including solar, batteries and even biodigesters. In the UK, farmers are leasing land to energy companies, which have installed renewable energy infrastructure such as solar panels. According to the UK National Farmers’ Union, on-farm generation produced 10% of the UK’s energy needs, accounting for 70% of solar power nationally.

But this example seems to be one of the few that doesn’t present a dilemma over future food security. While there are opportunities for the food industry to tackle rising costs, many of these involve a trade-off between costs and yields, and some could jeopardize a future ability to produce food at the volumes required to feed the world.

Farmers Reduce Fertiliser Volume

Likewise, farmers have been consistently reducing fertiliser use over 2022 given it has become one of their costliest inputs. Some have redistributed applications of manure and fertiliser to minimise costs. We wrote about how farmers are combatting high fertiliser prices and shortages.

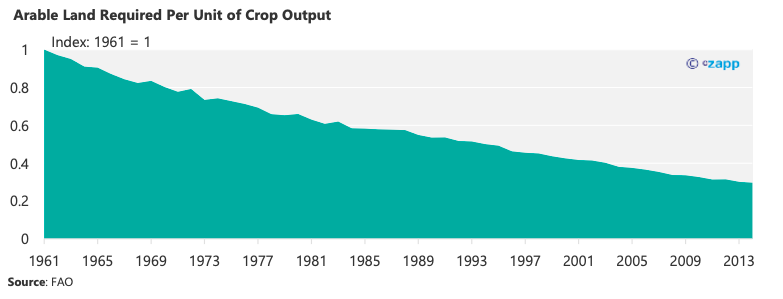

But reductions in fertiliser use over the long term could be disastrous for global agriculture. Fertilisers have helped to increase yields to feed a growing population, and any reduction in these yields could prove critical, especially for poor countries.

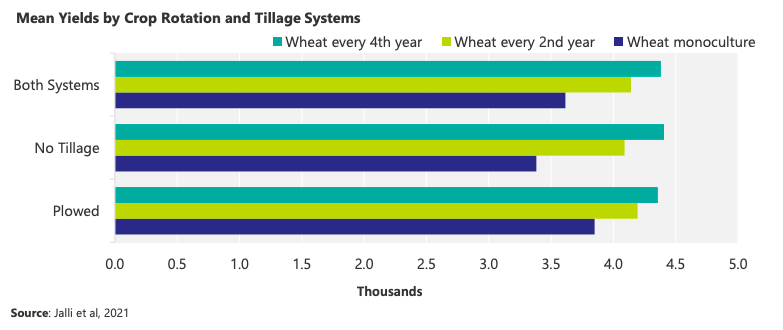

Some of the impacts of the fertiliser price rise could be absorbed by widescale adoption of organic farming. Crop rotation has been found to increase yields while limiting damage to soil. In a study of wheat crops, the best results were seen with planting every fourth year with no tillage.

However, crop rotation comes with drawbacks. Certain crops have higher values than others, and farmers are more likely to plant crops that yield greater economic value than those that can help preserve long-term soil quality.

Producers Call for Food Price Rises

Rising costs have prompted farmers to call for a rise in prices. Leading cocoa growers in Ivory Coast and Ghana are lobbying the chocolate industry to pay more to help farmers absorb these costs.

Several restaurant chains are charging more. Global coffee conglomerate Starbucks said in its second quarter earnings call this May that one of the ways it has been offsetting margin pressures caused by inflation is by accelerating price increases. McDonalds said in its first-quarter earnings that its sales growth during the quarter was “driven by strategic menu price increases.”

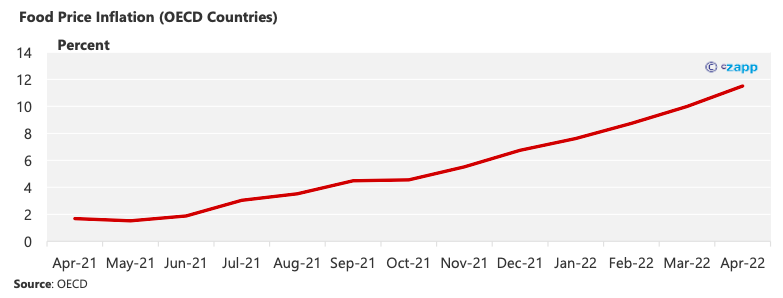

But the solution is not quite that simple. With inflation growing, pressure on consumers is already high. In April, annual food price inflation in OECD countries was 11.5%.

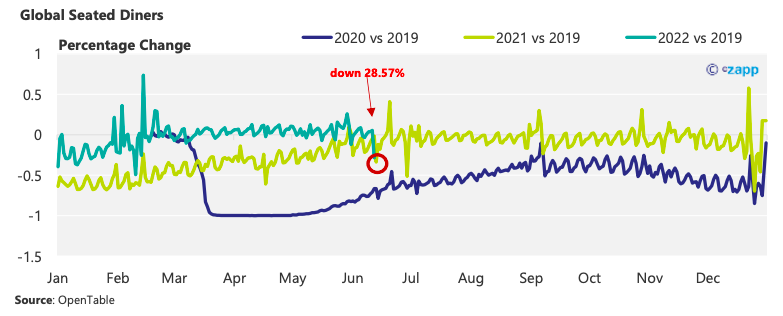

These effects of this cost pressure are already starting to feed through in a slowdown in discretionary spending. After a slow start to the year caused by the omicron variant of the coronavirus, the number of seated diners in 2022 has continuously exceeded even 2019 numbers. However, this began to fall in mid-June.

Even those consumers who are still eating out are opting for more budget-friendly options. McDonald’s CEO Chris Kempczinski said in May that low-income consumers have started ordering cheaper items or downsizing their orders.

While producers believe additional costs should be passed on, there have been calls by consumers to cap food prices or risk a health crisis. Australian supermarket Woolworths has announced a price freeze on items such as pasta, bacon and frozen peas but has declined to do so on its fresh produce.

There have been recent reports of a single iceberg lettuce costing AUD 12 (USD 8.38) in supermarkets. Typically, the product costs about AUD 2.80 on shelves.

Brazilians Shorten Supply Chain

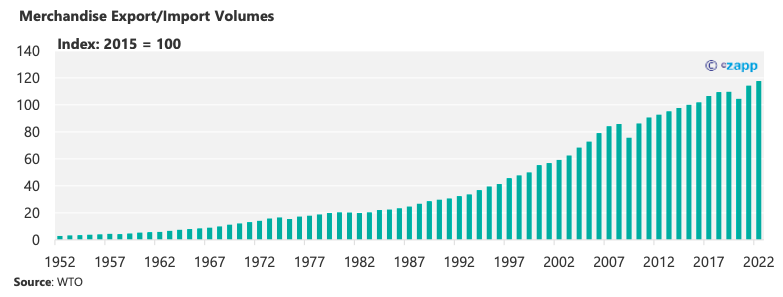

There is no doubt that the global supply chain has lengthened in the past 50 years. World trade in goods and merchandise has increased exponentially, meaning there is more need for a greater number of actors.

Without a host of logistics companies, traders, banks, brokers, insurance firms, wholesalers and retailers, it would be impossible to access the variety of foods we consume on a daily basis. Between 1975 and 2008, the average supermarket shelf inventory skyrocketed by 425% to about 47,000 items from just under 9,000.

But with snarled up logistics and tight margins, small-scale farmers in Latin America have been trying to shorten supply chains. Startup Paypayas from Brazil was established to eliminate banking charges by allowing consumers to buy directly from farmers using an app. Ecuadorian company Barnana buys plantain directly from farmers at 30% above the market rate.

The benefits of a smaller supply chain are evident. Overheads can be kept low; instead of being eaten up by spiralling transportation and logistics costs, producers can charge more without adding greater pressure on consumers.

But there are also drawbacks to this approach. Without our current massive global supply network, there would be much less variety. No longer would mangoes be readily available in Europe and, as we are now seeing, the Middle East and North Africa would struggle to get their hands on wheat – a dietary staple.

Countries Raise Funds to Restore Agricultural Land

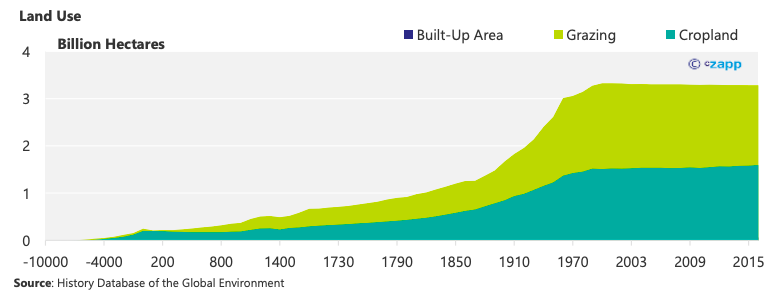

There is no question that the world needs more food. On the surface, one solution to this would be to increase agricultural land. In Ivory Coast, in fact, efforts are being made to raise more than $1 billion to restore forests and expand food production.

While greater food supply seems like the ideal solution to bring costs down, there are more complex considerations. Firstly, larger expanse of land without higher density would most likely require higher outlay on inputs such as labour and fertilisers. The costs of both inputs are rising fast.

Another consideration is the fact that agricultural expansion on a wide scale is unviable. Already, half of the world’s habitable land is used for agriculture. Expansion of agricultural land is also responsible for the largest environmental impacts due to biodiversity loss.

Food Producers Turn to Substitutes

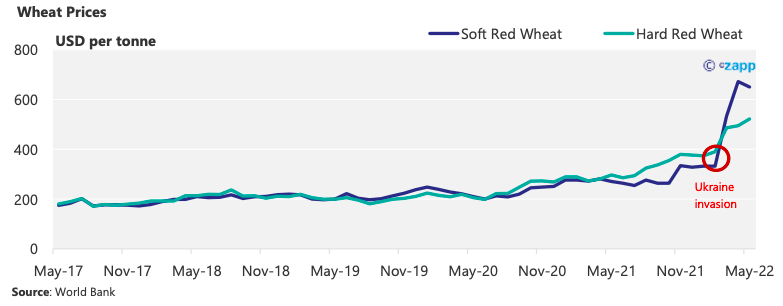

Substitutes are one way that governments and food producers are combatting food price rises. The price of wheat, for instance, has risen exponentially since the war in Ukraine started in February.

KFC in Australia, faced with the high price of lettuce, is substituting it with cabbage in its products. In the UK, fish and chip shops are stepping away from the popularly used cod and haddock and seeking new species of fish that can be used as a cheaper alternative.

With wheat now so costly, food producers in African countries including Kenya, Egypt and Nigeria are mixing cheaper alternatives into breads, pastries and pastas. Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni is even promoting the use of cassava flour as an alternative to wheat.

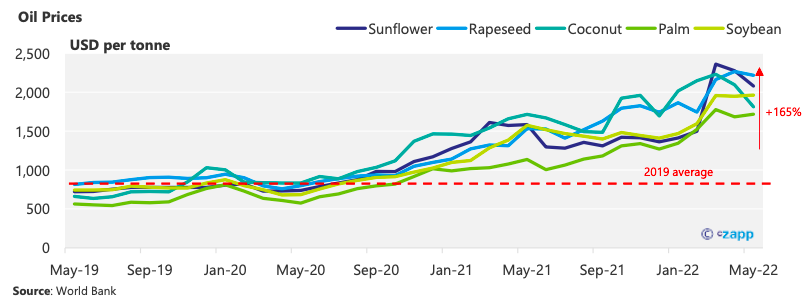

However, this strategy has only seemed to cause price rises over a broad spectrum of products. For example, the shortage of sunflower oil due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine caused many to shift to alternatives such as coconut oil, soybean oil, rapeseed oil and palm oil. This in turn has caused prices to move sharply upwards.

Average cooking oil prices rose to just shy of USD 2,000 a tonne in May, up 165% from the 2019 average of USD 740/tonne.

FAO Advises Governments to Provide Support

This month, the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation proposed that low-income countries should be equipped with a Food Import Financing Facility (FIFF) that “helps ease their immediate food import financing costs”. With a suggested funding level of USD 25 billion, the program would cover the 62 most vulnerable countries with a population of 1.78 billion.

In a follow up interview, FAO economist Monika Tothova suggests help for those most affected through provision of “targeted assistance [such as] vouchers, direct payments, safety nets.”

But this has proven to be easier said than done. The World Trade Organisation made a recent agreement on food policy, which would see member countries pledge to keep markets open, not restrict exports and increase transparency in a bid to alleviate the food crisis.

But despite broad support, Egypt, Sri Lanka and India were all reluctant to agree to the pledge. Egypt and Sri Lanka – both net food importers – are already experiencing extensive food supply difficulties and are struggling with rising food costs. India – in a strong position due to its extensive wheat stockpile – aimed to hold out in the hope of negotiating on other WTO agreements.

Meanwhile, protectionism is rearing its head. This week, the UAE decided to suspend exports and re-exports of Indian wheat for four months. All non-Indian flour exports must be granted export permission from the Ministry of Economy.

India has said it will also limit sugar exports, while Malaysia banned poultry exports. Indonesia temporarily banned the export of palm oil but walked the restrictions back after three weeks. China already had imposed an export ban on fertilisers in October but analysts at Bank of America expect this to be extended through mid-2023.

Concluding Thoughts

- While some measures are required to address food-price rises in the short term, if applied long term many of these measures put future food supply at risk.

- Renewable generation is an innovative way to cut energy costs but not all farmers have access to favourable agreements or infrastructure.

- A reduction in fertiliser volumes may reduce costs in the long term but it jeopardises yields in the long term and potentially requires greater land use.

- A shorter supply chain would solve some problems but would require a change in consumption habits.

- Long-term dependence on substitute products will only lead to more widespread price rises.

- Subsidies and government support programs are likely to come up against some political backlash.

Other Insights that may be of interest

What the Energy Crisis Means for Inflation & Commodities

Six Indicators the Supply Chain Should Monitor

Interactive Data Reports that may be of interest …

Consecana Panel

CS Brazil Weather Update