Insight Focus

European gas prices have risen amid geopolitical tensions ahead of winter. Coal is becoming more competitive at the power generation margin, meaning EUA demand may increase.

An Opening for Coal

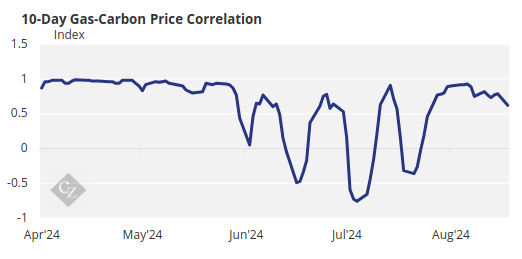

Slowly mounting concerns over Europe’s supply of natural gas over the coming winter has begun to drive gas prices higher, but carbon appears reluctant to follow, breaking a correlation that has been in place for most of last year and this.

Source: ICE

The role of carbon permits in the power sector is to make the cost of burning coal for power generation more expensive than that of natural gas, and up to 2021 EUAs were performing this function well.

But rising geopolitical tensions ahead of the commissioning of the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline, followed by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine pushed gas prices up as much as seven-fold, making the fuel uneconomic as a generating fuel for electricity.

Coal prices also rose, but only as much as four-fold, and this meant that coal-fired power became more profitable for an extended period of time.

Carbon had also been dragged higher by the general increase, but not by enough to keep gas at the top of the merit order, but by the end of 2023, gas resumed its place at the top.

Throughout 2024, natural gas has been favoured over coal in power generation, thanks to plentiful supply and comfortable storage levels after a relatively mild winter in 2023.

EU Gas Prices Rise

But as the market starts to eye the coming winter, natural gas prices have begun to lose their advantage over coal.

Front-month TTF prices have risen to their highest levels in the year to date, driven by rising geopolitical tension in the Middle East as well as Ukraine’s recent offensive in the Kursk region of Russia.

In addition, the current long-term gas transshipment contract between Russia and Ukraine, which permits Russian gas to flow west into Europe, is set to expire at the end of the year. Despite the conflict, it has remained in both countries’ financial interest to maintain supply, but there are as yet no talks over a renewal of the contract.

And to be clear, Europe has no intention of buying pipeline gas from Russia once the contract ends; instead it is casting its net wider for varied sources, and this means liquefied natural gas cargoes from the US, the Middle East and Africa, among others.

As the chart below shows, the operating margins of gas-fired power plants are now less than those for units that burn coal. The graph depicts the net difference between the clean dark spread – the margin for coal plants – and the clean spark spread, the operating profit for gas units.

A positive reading means that coal’s margin is better than that for gas, and should encourage utilities to despatch power from coal-fired units.

EUAs Decouple from Natural Gas

To many, the swing in favour of coal is a logical development. If Europe’s winter gas supply is threatened, or if the coming season proves significantly colder than the last two winters, demand for natural gas will be much higher, the draw on storage will be greater and power generation will need to take second place to domestic heating.

The current rise in gas prices reflects both this medium-term outlook as well as more immediate geopolitical concerns. Investment funds have been steadily amassing larger and larger long positions in TTF gas, while the rate at which European storages have been filling has slowed and is now more or less equal to where it was at the same time last year.

What does this mean for carbon?

So far this year EUAs have tracked natural gas prices closely. That’s to be expected since gas has been the favoured generation fuel for many months. As gas prices rise, the fuel becomes comparatively – if not absolutely – less competitive compared to coal, and some coal-fired capacity becomes profitable at the margins.

But in a situation where gas generation is either uneconomical or needs to switch off to preserve supplies, then demand for carbon permits should rise since burning hard coal emits twice as much CO2 as gas.