Insight Focus

Co-processing is an alternative to blending SBC with jet fuel. This method combines conventional crude oil with alternative feedstocks early in production. Both co-processing and SBC blending contribute to sustainable aviation fuel, each with unique benefits.

For the most part, the manufacture of Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) is achieved through the production of an Synthetic Blend Component (SBC), which is controlled by the standards set in ASTM D7566—a guideline from ASTM International that outlines the requirements for producing and blending synthetic aviation fuels.

This SBC is then blended with Conventional Jet Fuel (CJF) to create SAF, following the specifications in EI1533 (reissued in February 2025). In this process, the two basic components of SAF are made separately and then combined.

The alternative is to process two separate feedstocks together: one conventional crude oil and the other an alternative, non-traditional feedstock. The resulting suite of products is sustainable to a degree, depending on the carbon intensity of the alternative feedstock and the allocation by mass balance.

This is an alternative pathway to SAF via so-called ‘co-processing.’ This approach brings the conventional and alternative components together at the beginning of SAF production, rather than at the conclusion.

So, which route should be chosen?

Other Production Routes

For SBC production, a separate processing unit, feedstocks and handling systems are required. This demands many new and novel technology platforms, along with dedicated operational support.

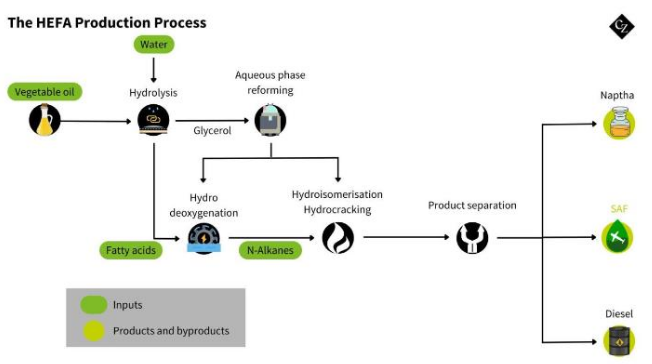

The simplest route is via HEFA – which is simplest because the starting material is a hydrocarbon with a small amount of oxygen attached. Processing requires the removal of the oxygen through hydrogenation, followed by cracking to bring the boiling range within specification.

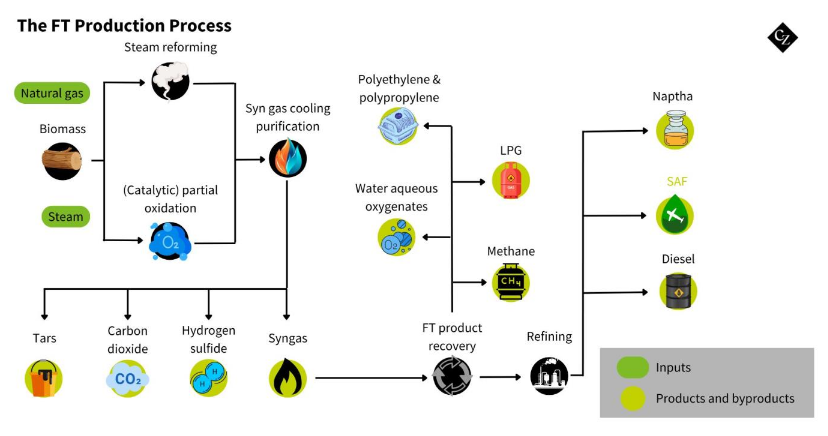

The most difficult route is starting from CO2 – this requires the removal of part of the oxygen to produce CO, then the addition of more hydrogen through Fischer-Tropsch chemistry to produce liquid hydrocarbons.

Other processing routes utilise feedstocks in between these two, with energy input decreasing on a sliding scale. Other factors, such as process robustness and reliability, linked to risks of contamination and catalyst poisoning, add further uncertainty, which may partly explain the slow uptake.

Co Processing

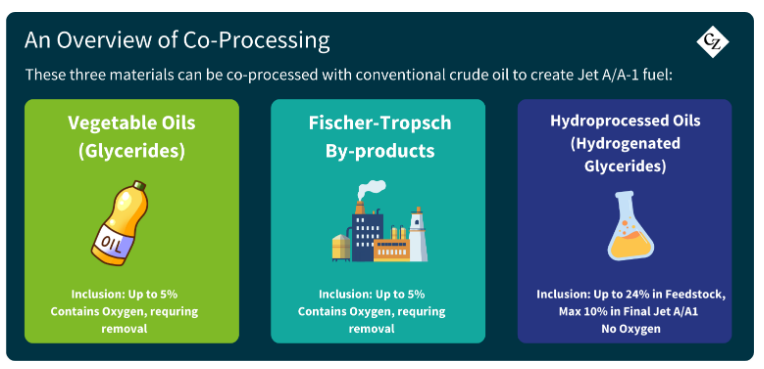

For co-processing, what materials may be co-processed with conventional crude oil? Currently, there are three:

-

Vegetable oils, also called glycerides (which can also be feedstock for Annex A2 HEFA SBC), may be included up to 5%.

-

Fischer-Tropsch by-products (from, e.g., Annex A1 SBC) may be included up to 5%.

-

Hydroprocessed oils (hydrogenated glycerides) may be included up to 24% in the feedstock, although the maximum in the final Jet A/A-1 is 10%.

Feedstocks 1 and 2 above contain oxygen, which must be chemically removed (since oxygen is not allowed in jet fuel) and thus can only be present at a lower concentration of 5%, ensuring that refining hydrogenation capacity isn’t overwhelmed.

Feedstock 3 is a hydrocarbon, most like crude oil components, and is therefore permitted at a higher level, currently 24%.

Through mass balance— i.e. apportioning the non-conventional starting percentage across the suite of products—the amount included in jet fuel is strictly controlled. It is also important to note that any jet fuel co-processed component does not count toward any blending limits with SBC later in the distribution system.

Overall…

Both routes to SAF offer their own advantages. The SBC route offers certainty in terms of processing separation, while the co-processing route offers a simpler, quicker and lower-investment technology.

Together, both routes provide the maximum opportunity to reduce the carbon intensity of flying and are complementary. In the short term, co-processing is an excellent option until SBC production ramps up.

We’ve discussed the manufacture, composition and blending of SAF—next, we will explore the availability of SBCs.