Insight Focus

- Expiration date labels have become more and more complex over the years.

- As the cost of food rises, consumers are paying more attention to what they eat.

- Simpler labels could help reduce waste and tame price inflation.

How Much Food Do We Waste?

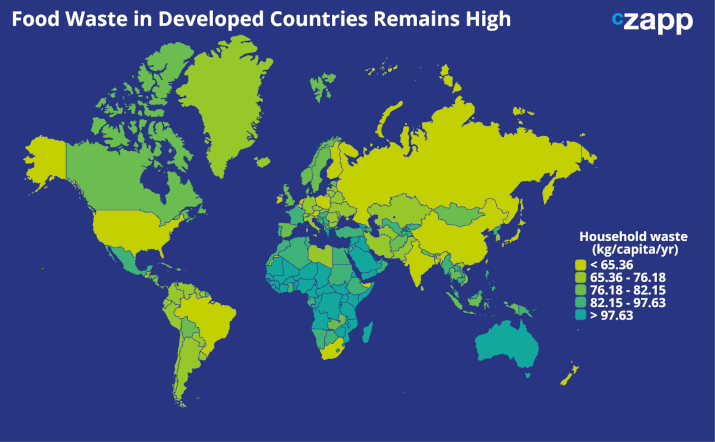

Globally, 569 million tonnes of food are wasted at the household level annually. Food wasted or lost across the supply chain accounts for about 6% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

In developing countries, food waste mainly caused by lack of proper storage and infrastructure. But in developed world, something else is causing waste.

The UK is currently struggling with a cost-of-living crisis. The food inflation rate remains high at 15.4% as of May 2023, which has an impact on buying behaviours.

Source: OECD

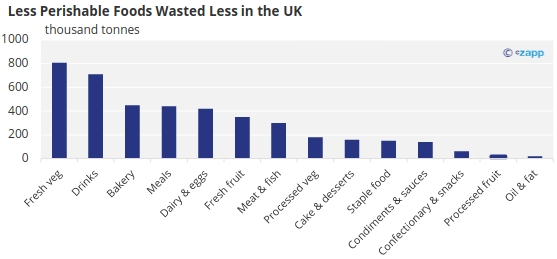

In the UK, more waste is seen across perishable items such as vegetables baked goods, meat and dairy products. There is less waste across longer life items such as oils, confectionary and condiments. In the US, most waste is across dairy products and fresh vegetables.

Source: OECD

This could suggest that there may be some room for improvement when it comes to food education and product labelling.

Labelling Discrepancies Abound

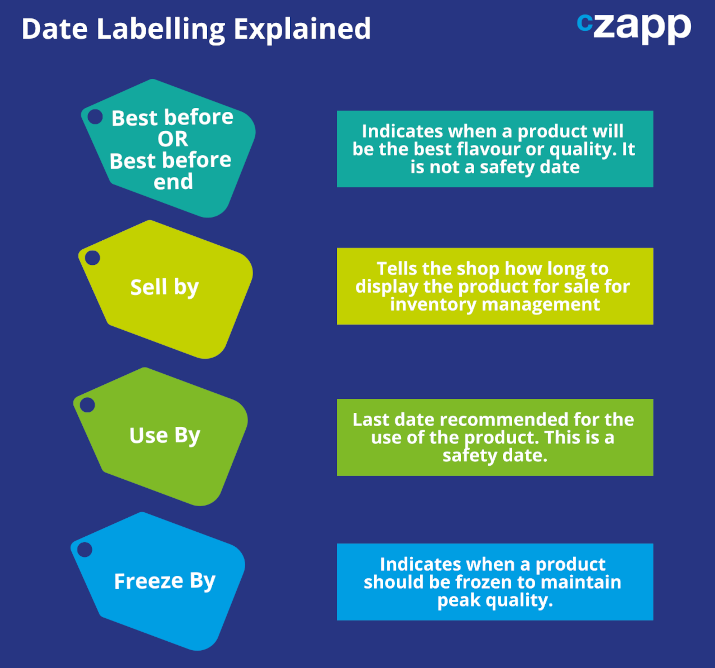

There is undoubtedly confusion over food expiration labels. “Confusion mainly arises over the difference between ‘use by’ dates (which are a food safety measure) and ‘best before’ labels (which are about food quality),” says Peter Jackson, Co-Director of the University of Sheffield’s Institute for Sustainable Food. “The danger of letting supermarkets decide which labels to use is that consumers will face a plethora of labels in different retail spaces which may create further confusion.”

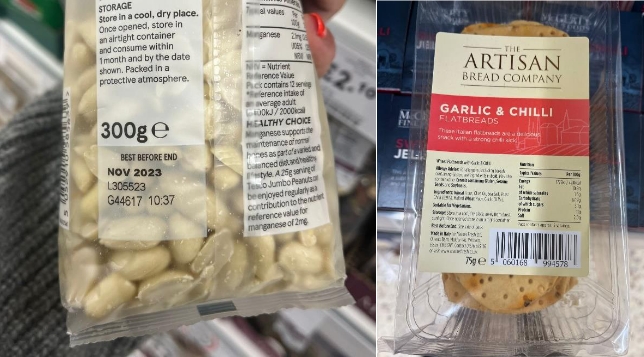

To illustrate this point, I took a trip to the local supermarket and found a number of hugely different labels. Some, including peanuts and flatbreads, included ‘best before’ or ‘best before end’ dates.

These pre-packaged sweet potato fries contained a ‘use by’ date.

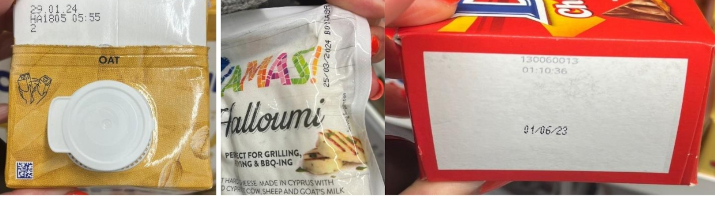

Other food products (oat milk, halloumi cheese, confectionary) simply printed dates without any guidance.

While a ‘best before’ date was surprisingly included on a bag of ice…

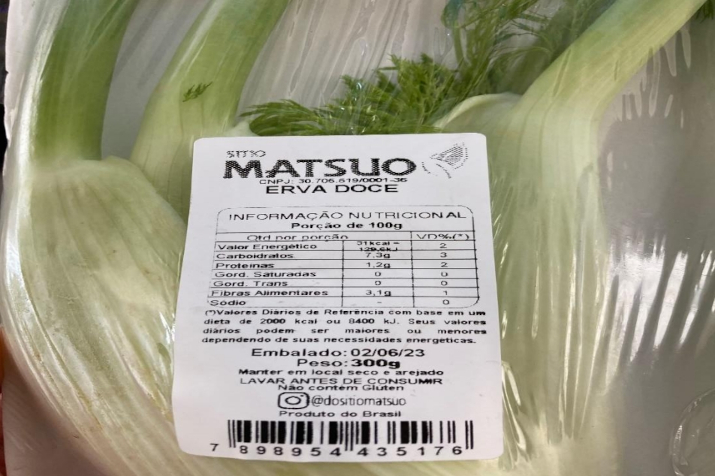

… there was a notable absence of guidance on several fresh vegetables.

So, what does it all mean? Well, it can be confusing.

Lessons to be Learned

While food labelling in Brazil is not uniform, it does follow a certain pattern. There is no distinction made between ‘best before’, ‘use by’ or ‘sell by’ dates.

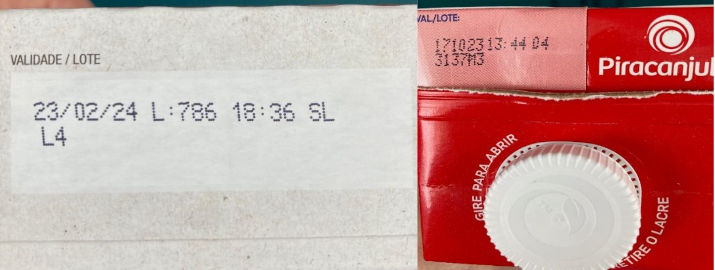

These jasmine rice, chickpeas and vegetable stock packages all contain lot numbers, alongside manufacturing and expiry dates.

On these oatmeal and milk cartons, there is simply a lot number and expiry date.

And fresh fruit and vegetables like this fennel only contain the packaging date.

In Brazil, according to Embrapa, only 10% of food loss and waste occurs at the household level. This could suggest that a more simplified food labelling system could help reduce food waste in countries such as the UK and US.

Addressing Consumer Confusion

‘Use by’ dates are designed to prevent illness from consumption of bad or rotten foods. Generally, the foods containing ‘use by’ dates are perishable and at a higher risk of containing listeria, which is why ‘use by’ dates should be seen as a final deadline for eating products.

‘Best before’ or ‘sell by’ dates tend to be found on more shelf stable products, meaning that they can still be eaten after the advised date, but the quality may not be as good. But in our modern, busy society, most of us simply don’t pay attention to this subtle difference, meaning a lot of food is thrown away on or before its ‘best before’ date.

And more confusion is added with preservation techniques. Remember those sweet potato fries?

They contain a ‘use by’ date, meaning they MUST be consumed before the mandated date. But if you look closely, you’ll also see they’re suitable for freezing, meaning they can actually last beyond this strict deadline if stored correctly.

“It’s not just about people’s attitudes towards expiration date labels but how those labels are configured,” Jackson notes. “It’s about the institutions and infrastructure that supports the current system which the public, understandably, find confusing.”

In response to confusion, some supermarkets are phasing out ‘best before’ labels, which should help reduce some avoidable food waste. Sainsburys announced last August that it would remove dates from over 230 fresh produce lines including pears, onions, tomatoes and citrus fruits.

The supermarket chain will also switch from ‘use by’ to ‘best before’ labels on its own-brand yoghurts after testing showed the ‘use by’ dates were leading to customers throwing these products out prematurely. Date labeling is not arbitrary but understandably, food manufacturers and retailers tend to err on the side of caution. This can result in overly conservative labels, generating more food waste.

Although it is against the law to sell an item past its ‘use by’ date in the UK, certain products do not actually require these, as long as they have a lot number. The list of eligible products is set out by the Food Standards Agency and DEFRA and can be found on the government website.

Another solution to the issue of food waste caused by date labelling is by educating consumers on preservation techniques. Some products, such as bread, can be frozen, while some vegetables can be pickled. Eggs can also be tested using water to tell if it has gone bad, and often the results do not correspond with the ‘use by’ date.

Retailers and manufacturers can help with education about leftover food. In its 2021/22 Retail Survey, WRAP noted that more retailers are including motivational messages, leftover recipes and behavioral tips on their packaging.

Lowering Demand Can Lower Inflation

Inflation is caused by higher demand than supply. When there is a fundamental supply shortage or an increase in input prices, as long as people are still willing to buy, the price will rise. This has been a huge factor in food inflation.

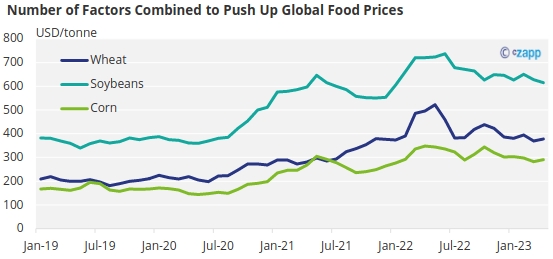

Several issues have created a shortage of agricultural supply in recent years, including Covid-19, weather events, energy costs and the war in Ukraine.

Source: World Bank

But if less food were wasted, there would be less demand, which would temper food inflation. So how do we do this?

The rising food prices have already generated some behavioural changes that could tackle waste, including buying less food, storing more in the freezer and paying more attention to dates. ‘Wonky’ veg is also becoming more popular as consumers pay more attention to price and less to how the products look.

But in some cases, the pendulum could be swinging too far in the other direction as some report eating food past its ‘use by’ date. “In the current cost-of-living crisis, there is evidence that consumers are using food that is beyond its ‘use by’ date,” says Jackson. “This isn’t because they are wantonly ignoring government advice but because they are faced with price rises that they can’t afford.”

And according to Jackson, it’s not just the consumer’s responsibility. “The onus should be on the government to regulate food manufacturers and retailers – and on them to adhere to the regulations,” he says. “Recent ‘food scares’ have shown that manufacturers and retailers don’t always have full control over their supply chains.”

Concluding Thoughts

- In the UK, 41% of household food waste is a result of products not used in time – this could either mean it has gone bad or is past the date indicated on the packaging.

- WRAP estimates that helping people understand labels better could reduce household food waste by over 350,000 tonnes per year.

- Changes can reduce food waste, reduce greenhouse gases and potentially bring down food inflation.

- But the responsibility for food safety is shared between the food industry, regulators and consumers.

- Some progress has been made by supermarkets’ willingness to remove ‘best before’ dates from products, but more needs to be done to simplify date labelling.

- The FSA, WRAP and DEFRA have compiled a guide for retailers on appropriate food labelling.