Insight Focus

Brazil should soon approve the Fuel of the Future bill. It was created to encourage the production and use of sustainable fuels. Among the proposals are goals for an increase in the mixture of ethanol in gasoline and targets for the use of biomethane and SAF.

Brazil has embraced decarbonization. In March, Congress approved a bill known as Fuel of the Future, which encourages the production of sustainable fuels, such as biodiesel, biomethane and sustainable aviation fuel (SAF). The new rule, which should be voted on in the Senate soon, also expands the blending of ethanol into gasoline.

Among other points, the law increases the blend content of biodiesel in diesel by 20% by 2030 and creates programs to decarbonize natural gas and for the production of sustainable aviation fuel. The market has already started to move, with prospects for new business.

We analysed the main aspects and challenges of the new legislation.

Biomethane

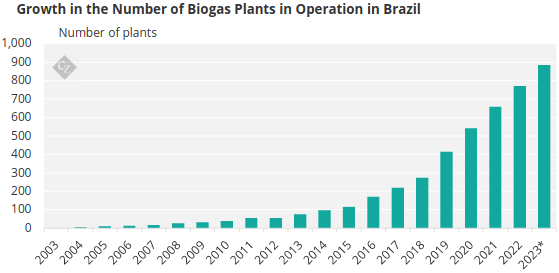

In recent years, biogas production has taken off in Brazil. More than 800 biogas producing units are in operation in the country, which corresponds to only 2% of Brazilian potential according to the Brazilian Biogas Association (Abiogás).

Source: CBiogás.

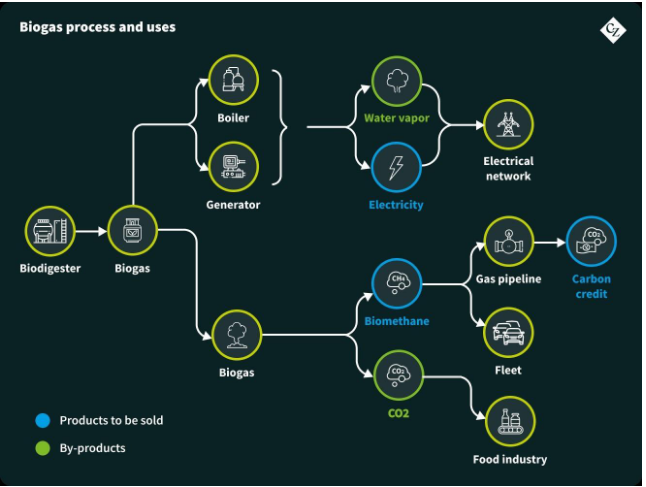

The production of biomethane, obtained from the purification of biogas (produced through the decomposition of organic raw material), is still incipient: there are only 20 plants in operation. The good news is that the new legislation should boost the sector’s growth prospects.

Considered a gas with high combustion power, biomethane can be used as a substitute for compressed natural gas to fuel vehicles. Biogas, in turn, is used to generate electricity and can also replace natural gas.

According to the new rules, 10% of the gas sold in Brazil must be composed of biomethane by 2034. There will be a gradual increase, with a mandatory percentage of 1% biomethane in natural gas from 2026.

To get there, the country will need to focus on producing sustainable gas. Atvos recently announced its intention to build its first biomethane plant in Nova Alvorada do Sul, in Mato Grosso do Sul, where it already produces ethanol. At the same time, the government of Mato Grosso do Sul made a commitment to reduce the ICMS (tax on circulation of goods and services) on biomethane from 17% to 1.8%.

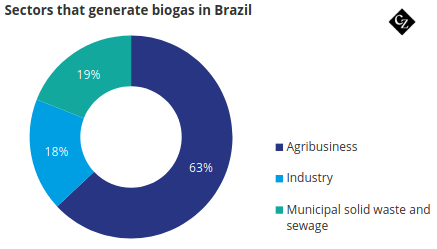

There are other projects underway. The Japanese Mitsui and the Brazilian Geo announced in April the creation of a joint venture to produce biogas and biomethane using sugar cane waste. Today, agribusiness is responsible for most of the biogas production in Brazil.

Source: Cbiogás

There are challenges that come with the sector and new legislation. One of the main points is the definition of an incentive policy for the production of biomethane, which should be discussed in the Senate.

Another important aspect is the development of new technologies and the scale necessary to reduce the cost of biomethane, which is higher than natural gas, and facilitate its insertion into the market.

SAF

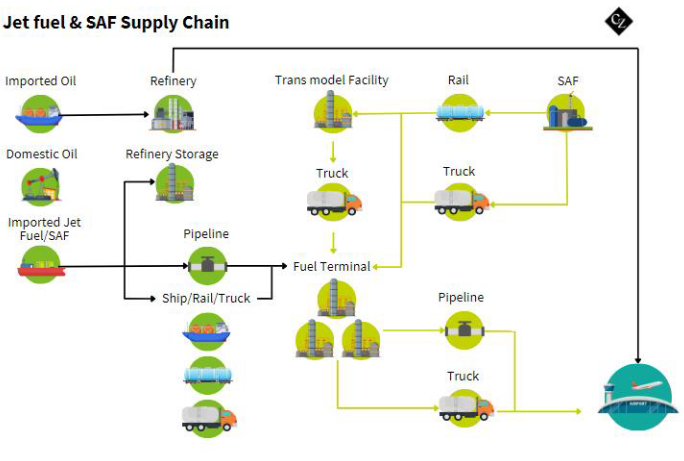

The bill also establishes the National Aviation Fuel Program. The objective is to encourage the production of SAF, mainly from ethanol.

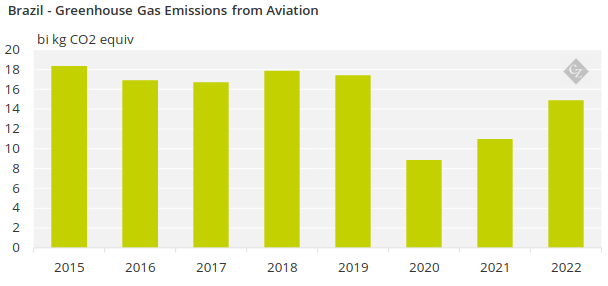

According to the new legislation, from 2027 onwards, airline operators will need to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions on domestic flights using SAF. Emissions reduction targets will gradually increase, starting at 1% in 2027. The idea is to reach up to 10% in 2037.

Source: Anac.

The law provides for some flexibility in meeting targets, under the supervision of the National Civil Aviation Agency (Anac). Airlines that do not have access to SAF at the airports where they operate, for example, may be exempt from meeting the emission reduction schedule.

Today, SAF represents less than 1% of the world’s aviation fuel, but its production is growing globally. In addition to sustainability issues, an aspect that benefits SAF production is the fact that its use does not require major modifications to aircraft engines and fueling infrastructure.

The ethanol industry is especially attentive to opportunities. Some plants, such as Raízen, Zilor, São Martinho and Ouroeste, have already obtained the ISCC Corsia Plus certification, which guarantees the international requirements necessary to produce SAF, and are preparing to enter this market.

Brasil BioFuels, in turn, must invest BRL 2 billion by 2026 to produce SAF in the Manaus Free Trade Zone. Petrobras announced investments of around BRL 600 million to produce SAF and biodiesel. Raízen, in turn, is already looking for a location to set up its SAF production unit.

A large part of the market, however, is awaiting definitions on possible incentives to produce SAF, considering the Future of the Fuel bill. It is also unclear how the methodology for calculating emission reductions will be carried out, which will be the responsibility of Anac.

Increased Ethanol Blending

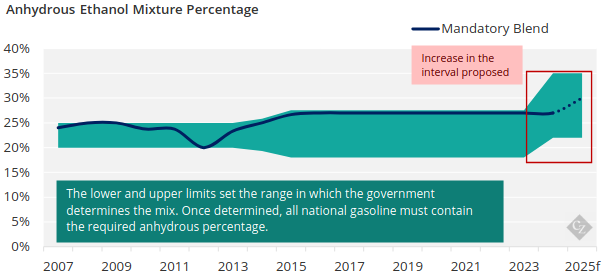

Another issue that the bill addresses is the increase in the blend of anhydrous ethanol with gasoline. Since March 2015, the anhydrous blend in gasoline is 27%. At the time, the law was changed to allow the blending range to be up to 27.5%. Today, the bill calls for the range to be revised to a minimum of 22% and maximum of 35%.

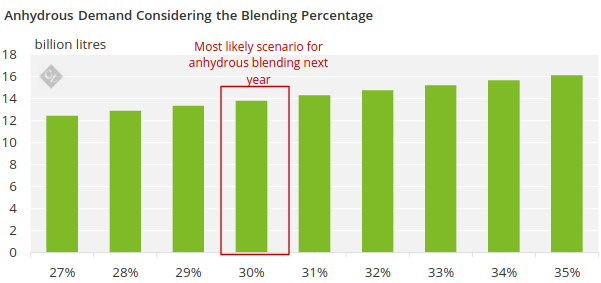

Once approved, many believe that by the next cane harvest (2025/26) the anhydrous blend should be determined at 30%. And in the future, if there is enough supply, it could go up to the 35% limit.

To give an idea of magnitude of this, today with a 27% blend, the national demand for anhydrous ethanol is 12.4 billion litres. Assuming the same demand for fuels and the same share of hydrous ethanol as in 2023, for every 1 percentage point increase in the mixture, the additional demand for anhydrous ethanol is almost half a billion litres.

In 2024/25, even with the increase in corn ethanol production, the total supply of anhydrous ethanol should remain at 12.2 billion litres.

Biodiesel

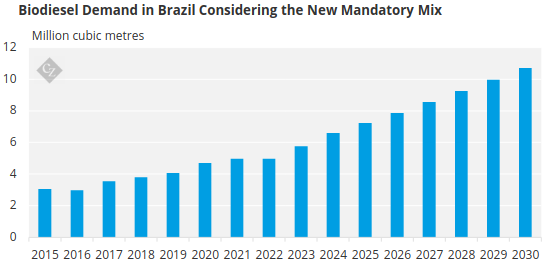

In 2024, the mandatory blending of biodiesel in diesel fuel increased from 12% (B12) to 14% (B14).

With the bill, the requirement will be 15% in 2025 (B15), a target that was previously only estimated for 2026. From then on, the objective will be to increase 1 percentage point each following year, reaching 20% in March 2030. But is this increase viable?

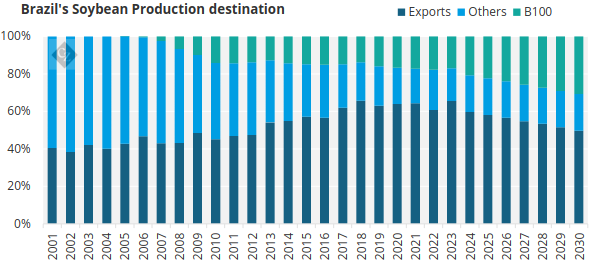

The main raw material for biodiesel production today is soybean oil. Currently, with the mandatory 14% biodiesel in diesel, Brazil demands more than 9.3 million cubic metres of B100 for the blending, a value that should reach 15 million cubic metres to reach 20% in 2030.

Source: Abiove

The big question revolves around soy. Today, 5.7 million cubic meters of soybean oil are produced to meet the demand for biodiesel, which, in the form of grains, represents 26.5 million tonnes. To achieve 20% blending, the soybean oil industry will need 49.2 million tonnes of soybeans — 22.8 million tonnes more than current demand.

In this way, the total share of soybean production that is destined to produce biodiesel (B100) would jump from 17% to 31%.

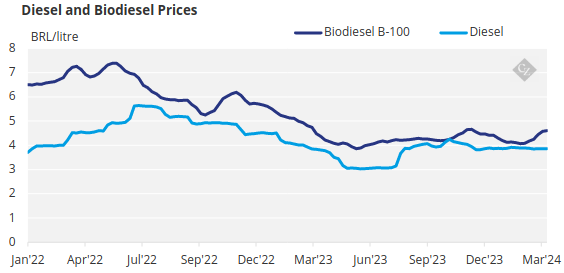

Regarding the impact on diesel prices at the pump, little change is expected by the market so far. The price of biodiesel has been falling since July 2022, operating at just a small premium to fossil diesel. The price has been pressured by the large global supply of soybeans and the low price of the grain (given that the price of biodiesel is linked to the price of soybean oil).

Therefore, even with the price of biodiesel being higher than that of diesel, experts estimate that the 2-percentage-point increase in the blending should not significantly impact the final price for the consumer. Unless the price goes up again…

Source: ANP

Furthermore, the bill will have a direct impact on Petrobras’ business, which has already expressed concern about the actions. The greater demand for biodiesel to meet the new blend will negatively affect the demand for diesel, harming the company’s investments, which controls 79.9% of the supply of diesel to distributors in the country.