- So far in this series, we’ve considered the grains and oilseeds supply chains.

- We’ve discussed the role of the farmer and the end-user.

- Today, we talk about how the international shipper fits into the story of inspection and certification.

Rules and Procedures

As you might imagine, international shipments are several times more complicated than domestic trades, and the value is similarly increased. A ‘Cape Class’ vessel of wheat, too big to go through the Panama or the Suez Canal, could easily be 150k tonnes and worth £30 million. Further complications occur because vessels can have split holds with more than one destination, or the contents can be traded to another buyer and/or destination whilst on the high seas.

Fortunately, a workable international system has evolved. In theory, the rules are simple enough, and are useful for most grains/oilseeds transported in bulk and container freight. Buyers/importers and (sometimes) banks issuing letters of credit are dependent on official certificates as a guarantee of the quantity and quality they’re purchasing. The trigger is an import document or license from the importer (government, representative, or private corporation). Critically, the exporter should make the goods available for inspection in the country of origin (in this case the US) and the import document is sent to the nominated inspection company/agency, which could be commercial, government, or both as an inspection order.

Normally, inspection costs are paid for by the importer or government of the importer. If further inspections are required, these are charged to the seller. Any costs of presenting the goods for inspection, such as packing/repackaging and handling, are the responsibility of the seller.

The inspection should produce a ‘Clean Report of Findings’ and then a certificate to this effect can be issued. Once all required certificates of inspection are complete, they go to the exporter’s shipping forwarder stating the value of the shipment, names and addresses of exporter and importer, country of origin and importer’s customs code. Financial settlements, if not already complete, are made to the inspector. The goods are shipped, and once custom cleared at the importers’ destination, are available for further inspection locally, if needed. Many of the tests are similar to those described in the previous article, but one important additional consideration is a phytosanitary inspection and certification.

This serves two purposes:

1. It preserves the grain from infestation in transit.

2. It avoids introducing a new species to a country.

Fortunately, there are templates for contracts and none better than the UK Based GAFTA (Grain and Feed Trade Association) and FOSFA (The Federation of Oils, Seeds and Fats Associations Ltd). In the case of the GAFTA, they claim 80% of the world’s grains and animal feedstuffs are traded on their contracts. The contracts are important because trading under these terms provides legally binding arbitration in the case of any disagreement and avoids costly court time. For the inspectorate, GAFTA has clear methods and descriptions of analysis. They also exclude other conventions, such as the International Sales Act (1967), or the UN Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods (1980). Many commodities are sold on known specifications, such as US Winter Wheat (Grades 1-5) or Ukrainian Wheat (Grades A-E).

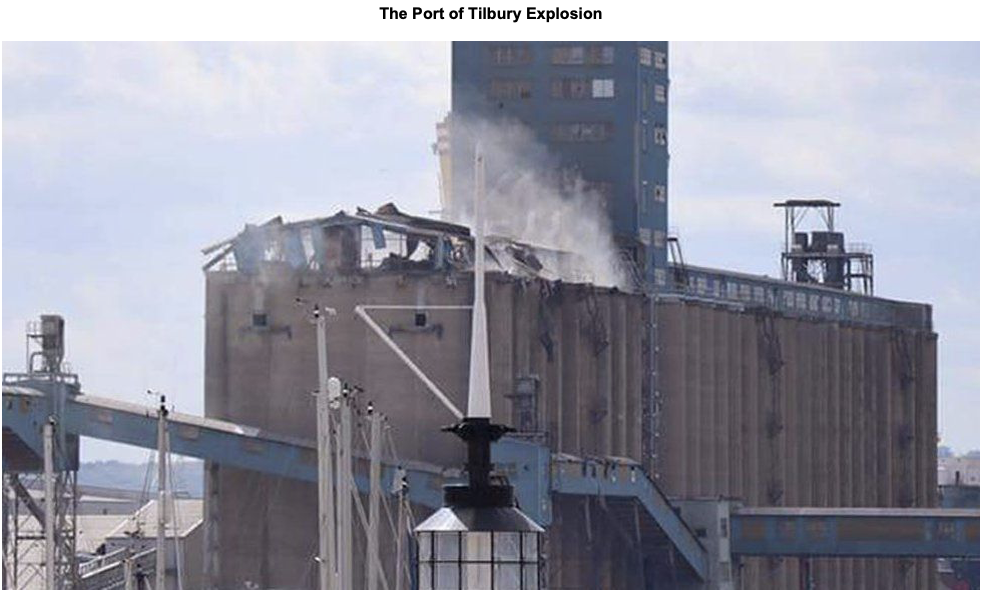

Vessels are also inspected under the auspices of the International Maritime Organization (IMO) International Grain Code 1991 as well as other requirements for the ship’s safety. Another key area of inspection is large port grain silos, which through dust accumulation can become explosive (or through electrical faults). This is what happened at the Port of Tilbury (UK) in July 2020, which literally blew the lid off the silo. Fortunately, there were no fatalities.

Source: BBC News

What Could Possibly Go Wrong?

As usual: a lot, but some of these things don’t directly relate to inspection and certification.

All the following are possible:

1. If goods arrive at the border of an importing country, they usually have to be re-exported to a nearby country for inspection.

2. Grains can heat up when bacteria that feed on carbon dioxide and water vapour are emitted into the air. High ambient temperatures accelerate the process until the temperature gets so high that it impairs the bacteria. This is called a ‘hot spot’ and, at this point, the heat moves outwards to damage the contents in the hold. The most common reason for this is when a poorly ventilated cargo in high ambient temperatures is delayed.

3. Seawater can enter into the ship’s holds, which would make that cargo (or part) unsalvageable.

4. Incorrect insecticide application rates can lead to infestation or heat-damaged grains near the engine room bulkheads.

5. Customs clearance is usually nationally controlled and go-slows or ‘heavy’ inspection are not unheard of.

6. There can be insufficient contractual detail on split loads of different grades, relating to costs and responsibilities of the parties.

A Case Study in Rule Mismanagement

Countries have rule books as to what’s acceptable for import, but not every facet is inspected.

Consider the case where American maize (corn) was shipped to China in November 2013 and Chinese inspectors detected an unapproved GMO (gene MIR 162) called Viptera from Syngenta AG.

Source: BBC News

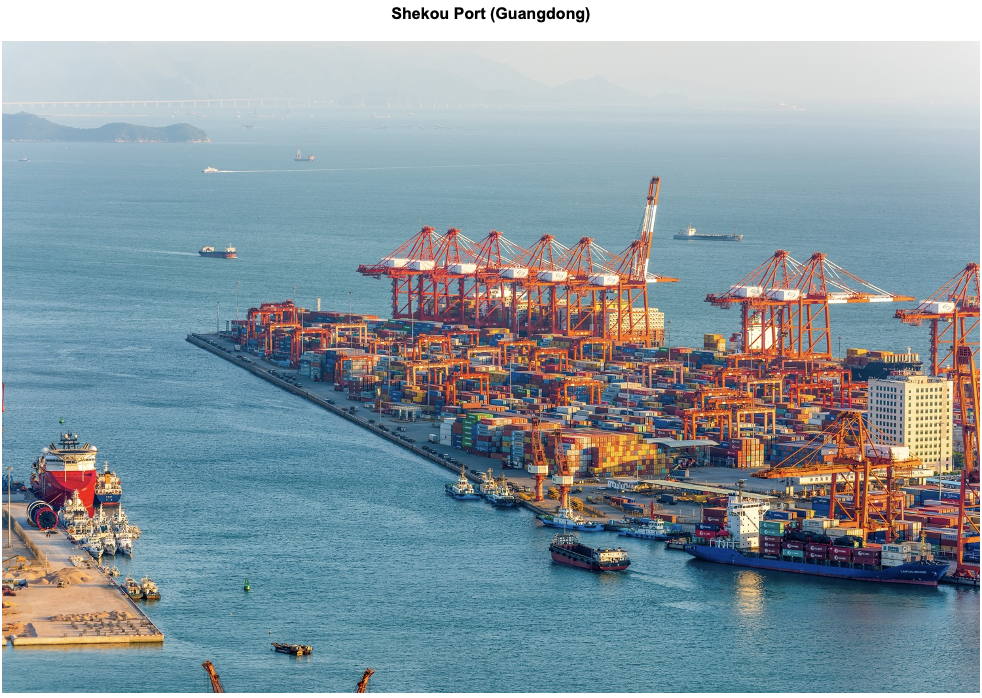

Allegedly, Syngenta had been telling farmers prior to planting that approval in China had been granted, or perhaps it was imminent. This is not something that would have been tested for. The 60,000 vessel had already been unloaded into port silos at Shekou (Guangdong) and had to be reloaded and shipped to a third country.

The result was a ban for part of a season on both corn and dried distillers’ grains with solubles (DDGS), a by-product of the corn-based ethanol industry. The cost to American corn farmers and ethanol distillers was estimated by US National Grain and Feed Association at $3 billion (US sorghum farmers benefited). The Chinese government also suffered as it had to buy substitute products including expensive Australian barley.

Other Opinions You Might Be Interested In…

- Inspection and Certification: The Basics

- Inspection and Certification: When Sampling Goes Wrong

- Inspection and Certification: Avoiding Trouble When Taking Samples

Explainers You Might Be Interested In…