- Last week, we covered the basic principles of Testing, Inspection and Certification.

- Here, we consider a key part of the testing process, namely sampling.

- Sampling is important as, if it’s carried out incorrectly, crops can become worthless.

Get Your Sample Size Right

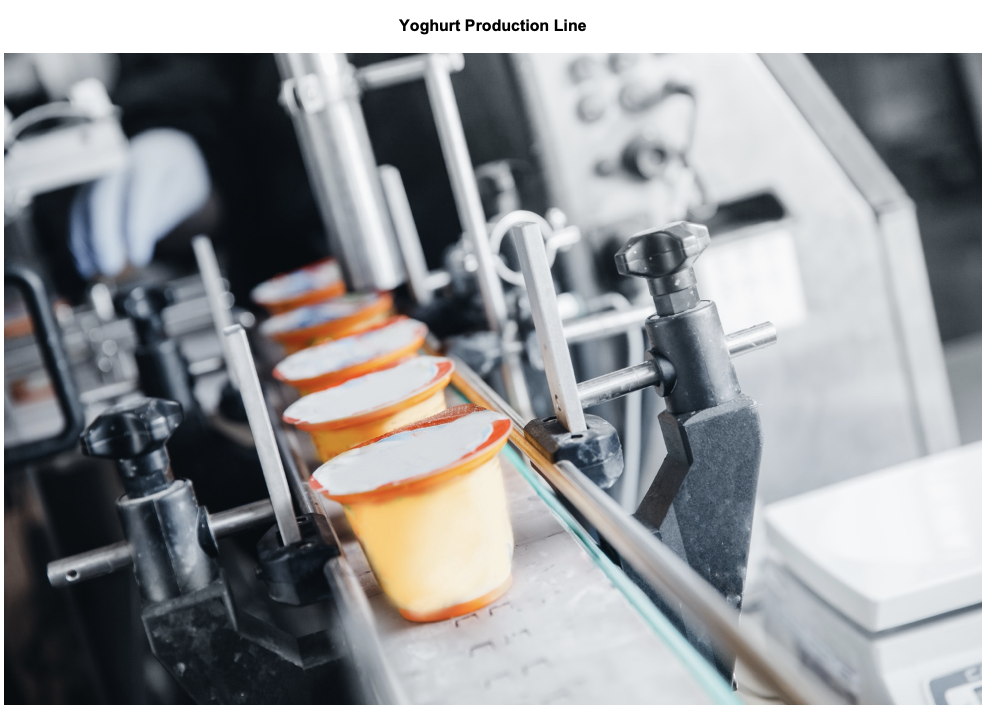

Let’s suppose we’re managing a yoghurt factory t and we want to test the lids on the pots to ensure they’re sealed and not damaged.

On one line, production is 20,000 pots per day, and we want to be 95% sure (confident) our result is within a range of plus or minus 5% MOE (margin of error).

MOE in the agricultural world is sometimes called the ‘tolerance’. I won’t bore you with the mathematical formulae as there are plenty of online calculators, but we need to sample 383 pots.

Now, let’s assume we double production to 40,000 pots. Amazingly, we only need to sample one more pot (384). The logic is the same as the numbers given in political polls and why people are sometimes baffled at the small number of interviews, but in truth, adding extra interviews in many cases would be an expensive waste of time.

Let’s take a different scenario.

We want to inspect the actual yoghurt in the 20,000 pots for any type of food contamination. That’s potentially a much more serious problem, so we increase the ‘sure’ (confidence) level to 99% and keep the margin of error the same at +/- 5%. Now we need to test 663 pots.

Finally, we want to be 99% sure our answer is now also within a range of +/- 2%. That’s pretty strict, so we must test 4,075 pots.

Random Sampling

The mathematics we’ve discussed won’t work if we don’t take random samples.

In the political poll example, if we only use a phone interview at night, we’ve meddled with the result. Similarly, if we test the yoghurt pots less when on a shift change, that would be the same. This is called ‘bias’ and it’s a lot more common than you might imagine.

True random sampling requires a great deal of thought.

What Else Could Possibly Go Wrong?

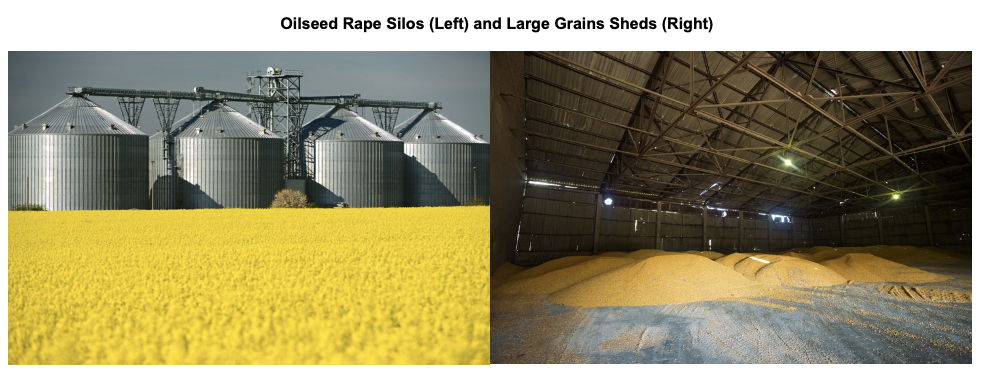

A lot. Let’s take a common example of an arable farm growing wheat (milling and feed), malting barley, and oilseed rape (OSR). The storage is a mixture of 50 tonne silos for the oilseed rape, and a large shed with under floor drying system and separate bays for different quality of grains.

The most likely problems are incorrect sampling and a lag between sampling and delivery, the latter of which we’ll discuss in the next Opinion.

Although this week’s examples are from an arable farm, many of the ideas and experiences can be applied in other areas, such as food and beverage production, on livestock farms, on the inspection of grain vessels, or in commercial silos.

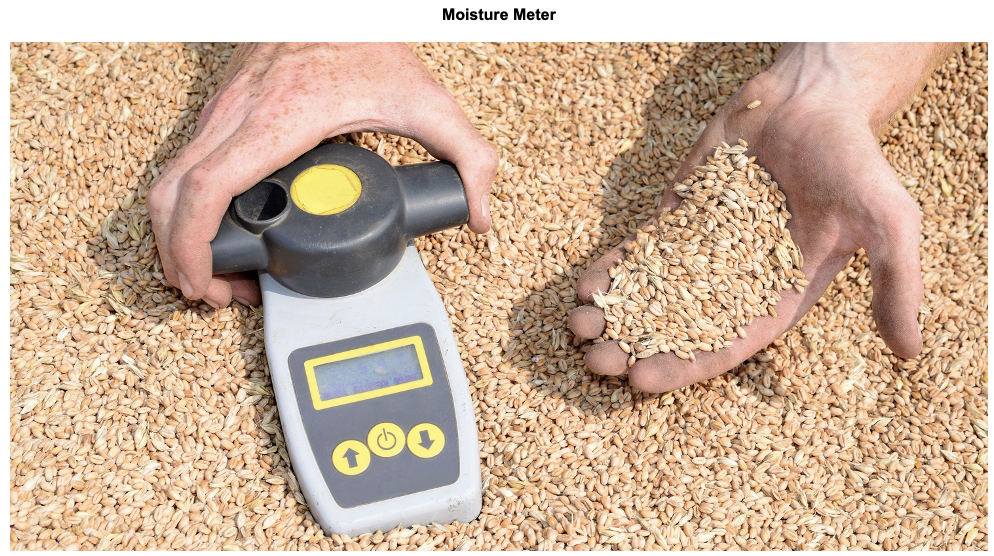

The grain sampling is usually carried out by the farmer first at harvest and then later by merchant’s representatives.

I’ve encountered the following errors in my career:

1. The farmer not understanding that the farmer’s sample that is not a final sample. Instead, it’s designed to assist the farmer’s decision making. The farmer will normally have basic equipment to carry out tests, but more sophisticated tests, such as those for protein, will need to be done at the merchant’s lab.

2. Incorrect sampling by the farmer at intake.

3. Insufficient sampling once the grain’s been cleaned and dried (if necessary). 250g samples are recommended for every 10 tonnes of grain.

4. Not having the moisture meter in clean and working order with new batteries.

5. Asking the merchant to sample the grain, rather than providing correct samples for their representative. Personally, I prefer a farmer’s sample if the grain’s going into a bin as at lot of the grain can’t be reached for sampling purposes in a bin. Similarly, it’s hard to get an accurate sample of grain if it is piled 5-6 metres high in a flat store (the spear’s normally only 1.5 metres long).

6. Incorrect labelling of the sample bags or using marker pens that are not permanent.

7. Over-drying or under-drying the grain/OSR. There are optimum moisture rates, such as below 14.5% for most grains and below 8% for OSR. Above these, there are opportunities for harmful fungi to proliferate, which can quickly turn valuable human consumption grades into cheaper animal feed grades. One of the worse cases I ever had was over-dried and over-heated OSR, where the heat had literally started to cook out the oil, rendering the crop virtually unsalable.

8. Insufficient cleaning or damage in cleaning, leading to rejections for ‘admixture’. For example, in OSR, rancidity and insect infestation rapidly increase if seeds are broken.

Conclusion

Harvest is the busiest time of the year and, in the heat of the moment, it’s easy to make mistakes in sampling. It’s also a time when temporary labour is frequently used, meaning some may have limited experience or training. Next time, we’ll look at the merchants and end-users because, yes, they sometimes make mistakes as well.

Other Opinions You Might Be Interested In…

Explainers You Might Be Interested In…