Insight Focus

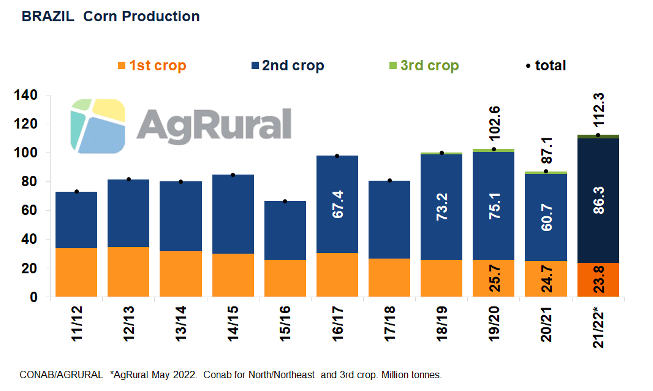

- The higher 2nd (safrinha) crop has contributed to Brazil being a major corn exporter.

- Chinese imports buoying prices could help unlock sluggish 2nd crop farmer selling.

- Brazil will have enough corn for substantial exports despite the lack of rain since April.

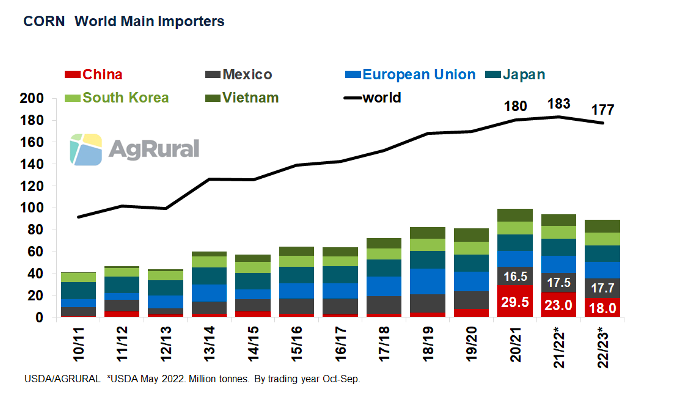

Apart from the Russian invasion making Ukrainian corn exports virtually impossible since late February, the biggest news on the international corn market since China became the world’s largest importer in 2020, was last week’s announcement that it has approved a phytosanitary protocol to allow corn imports from Brazil.

The move, certainly the most significant in years of negotiations, seems to have been speeded up by China’s need for more alternative origins for corn. After all, with Ukraine temporarily out of the game and restrictions still in place on imports from Argentina, the only major origin left for China was the US – a risky option at a time of very high prices and planting delays in the US, where the estimated corn acreage is 1.6m hectares less than last year, according to the USDA.

Throughout the last few years of negotiations, both the Chinese and Brazilian governments have been reluctant to disclose the details of the phytosanitary protocol. According to the Brazilian Association of Corn Producers (Abramilho), Brazil’s corn shipments to China, even after the protocol, still depend on a transgenic equivalence agreement. But the expectation is that both sides will want to speed up an agreement on this, and there are reports that trades for shipment in September have already been signed.

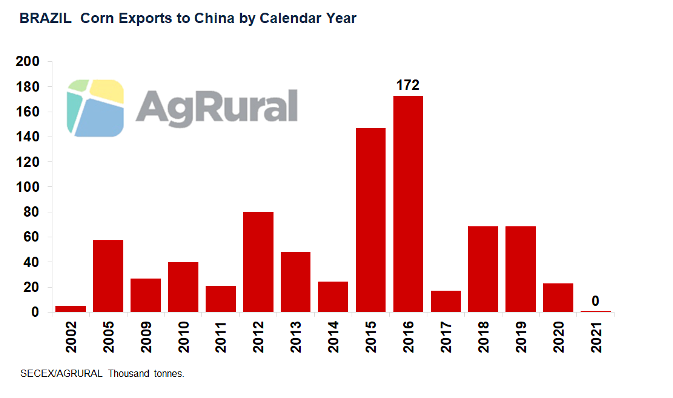

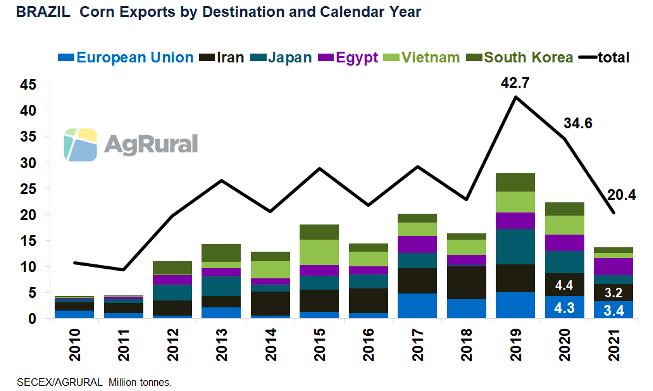

Chinese imports of Brazilian corn were not exactly banned, but they have been extremely small in recent years due to phytosanitary issues. According to Brazilian customs, the largest volume ever exported to China was 173k tonnes, in 2016 – less than 0.8% of the total corn volume shipped that year from Brazilian ports. If the phytosanitary and transgenic issues were to be completely surmounted, Brazil could export about 10m tonnes of corn a year to China — perhaps not in 2022, but probably by 2023.

Strong Domestic Market

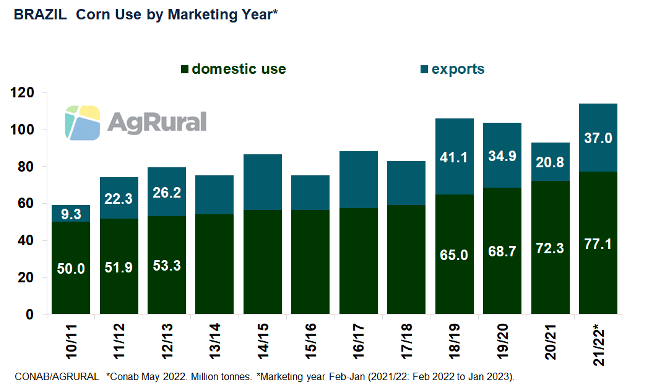

In contrast to soybeans, where exports are the main driver of the Brazilian market (in 2021, the country exported 86.1m tonnes, or 62% of its production), on corn the domestic market calls the shots. In the 2019/20 crop, when Brazil produced 102.6m tonnes of corn (a record-high that is being challenged in 2021/22), exports totalled 34.9m tonnes in the corresponding marketing year (shipments from February 2020 to January 2021). The domestic market, favoured by a thriving meat sector and an increase in corn-based ethanol production, consumed 68.7m tonnes. In the 2020/21 season, when the second crop (also known as “safrinha”) was hit by a severe drought, exports dropped to 20.8m tonnes, but domestic consumption rose to 72.3 million.

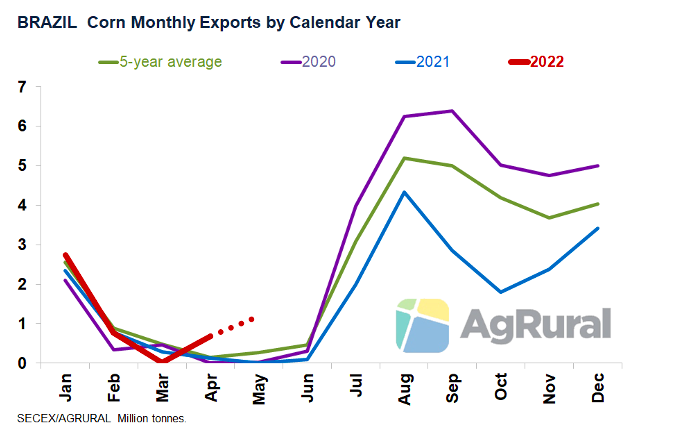

In 2021/22, total corn production is estimated by Conab (Brazil’s federal crop agency) at 114.6m tonnes, while exports and domestic use are forecast at 37m and 77.1m tonnes, respectively. AgRural forecast production at 112.3m tonnes, after a 5m tonne cut in early May due to dry conditions in central producing areas. Even so, the export potential was kept at 38m tonnes because international demand has been strong. In April, Brazilian exports set a record high for the month, with 690k tonnes shipped. In May, this feat is likely to be repeated, with more than 1m tonnes. In normal years, those two months are the slowest in Brazil’s corn export programme, which doesn’t pick up until July when the second crop comes onto the market.

No Frost Damage for Now

It is quite likely that there will be further cuts to the monthly production forecasts for the 2022 “safrinha” consultancies and official sources such as Conab will release in early June as the lack of rain continues to weigh on yield prospects in several states. On the other hand, and despite some scares in mid-May, frosts have so far been too mild to cause significant damage, keeping the corn fields of Paraná and southern Mato Grosso do Sul, where rainfall has been very decent, nearly free of weather stress. However, if losses are to be avoided it’s important that conditions remain favourable until the end of June.

Even if total 2021/22 production drops to somewhere between 105m and 110m tonnes due to dryness and/or low temperatures, Brazil will still have room to export up to 35m tonnes in the, 2022/23 marketing year. It’s not the record 41.1m tonnes shipped in 2018/19, but the volume would be similar to that shipped in 2019/20 and well above the 20.8m tonnes exported in 2020/21. Just as Ukraine, Argentina and the US. filled the gap left by Brazil’s crop failure last season, Brazil now seems to be able to cover part of the drop in Ukrainian exports – including those that would have been shipped to China.

Brazil Was Ready in 2012/13

Although domestic consumption dominates the dynamics of its corn market, Brazil has established itself as a major exporter in recent years due to increased production, improved logistics and the readiness with which Brazilian corn met world demand in 2012 and 2013, covering part of the massive crop failure in the US due to drought. From then on, Brazilian corn exports jumped to an entirely new level and attracted importers who were not exactly regular customers, such as Japan, Vietnam, South Korea and Egypt.

If China really enters the Brazilian market in the coming months, the most likely outcome will be fiercer competition for Brazilian corn, with a subsequent increase in export premiums at ports and in prices received by farmers – something more than welcome to help unlock the farmer selling which has been way slower than normal. Whoever is willing to bid higher will take the corn. If China prevails, other importers are likely to go in search of cheaper corn from Argentina and the US.

Brazilian corn could lose market share at home as the domestic market looks to cheaper imports from Argentina and Paraguay to deal with the toxic cocktail of rising production costs and lower meat prices, especially pork. But, in short, the answer to the initial question is: yes, Brazil is ready to export corn to China, and it is ready now.