Insight Focus

- Brazilian soybean production might have been systematically underestimated in recent years.

- This has been caused by poor physical stock surveys.

- Conflicting estimates make price formation harder.

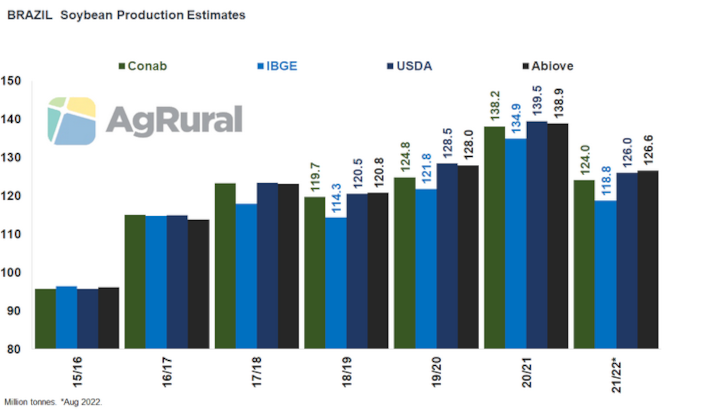

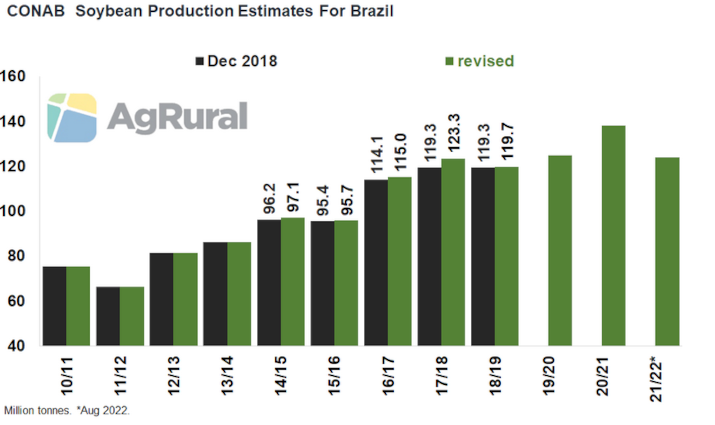

Brazil is already preparing to start planting its 2022-23 soybean crop, but some disparities in production estimates for the 2021-22 crop, harvested earlier this year, still exist. While official Brazilian sources put production at 124m tonnes (Conab) and 118.8m (IBGE), the USDA and Abiove (Brazilian Association of Vegetable Oil Industries) work with 126m and 126.6m, respectively. Private consultancies, for their turn, sees last crop’s production between 123m and 127m tonnes.

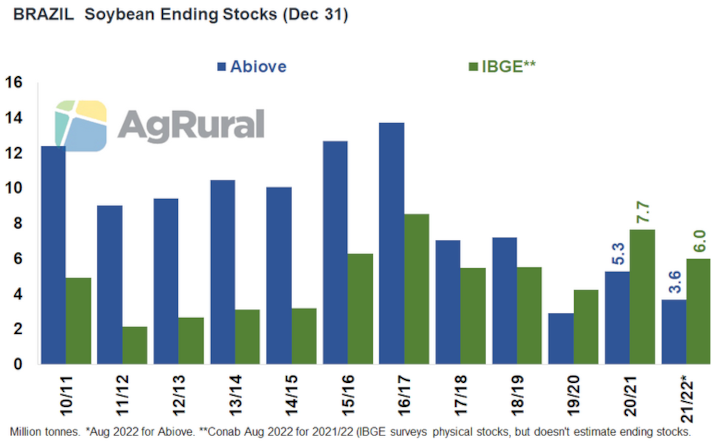

Exploring the difference between those numbers may seem preciosity, but the fact is that, in a year of crop failure, as is the case now in 2022, a few million tonnes make a difference when it comes to put together a supply and demand table and to calculate ending stocks for Dec 31 – an important input for price formation in the last months of the year and also for domestic consumption and exports in early January, when the new crop harvest is just starting.

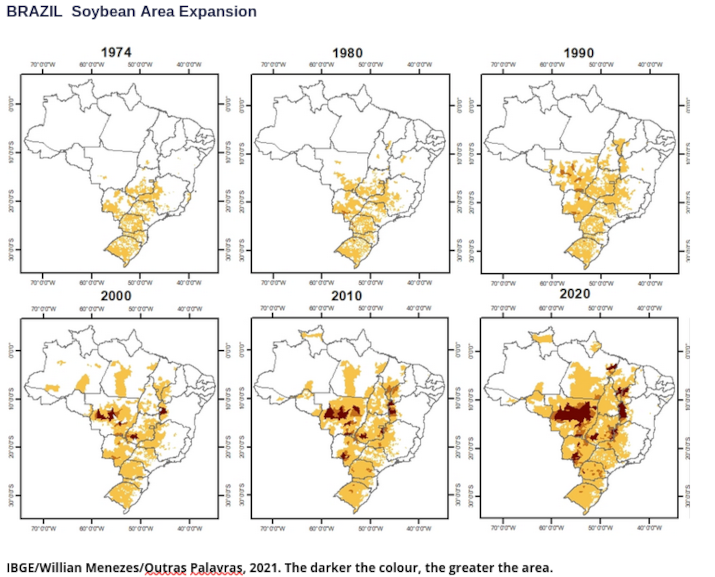

The differences between production estimates and upward revisions seen in recent years make some analysts speculate that Brazil’s soybean planted area would be, in fact, even larger than official sources say. This would happen, according to them, because part of Brazilian farmers would be planting in illegally deforested areas, which would not be mapped by official surveys. I personally don’t believe this to be the case. But, before explaining the reasons that lead me to think this way, I need to tell the story of how the size of Brazilian soy production became the subject of doubts and even conspiracy theories.

Record Exports

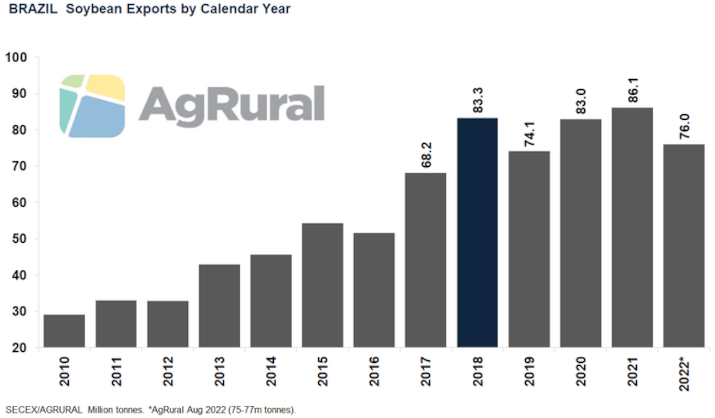

November 2018. About 70% of the estimated area for the 2018-19 soybean crop was already planted in Brazil. Normally, everyone in the market would already be focused on the new season. That year, however, the previous crop was still raising doubts. Brazil’s 2017-18 production, harvested in the first half of 2018, was estimated by Conab at 119.3m tonnes, a new record for the country. Exports, in turn, were projected by the agency at 76m tonnes, also a new record that, combined with strong domestic consumption, left ending stocks at less than 700k tonnes, one of the lowest ever.

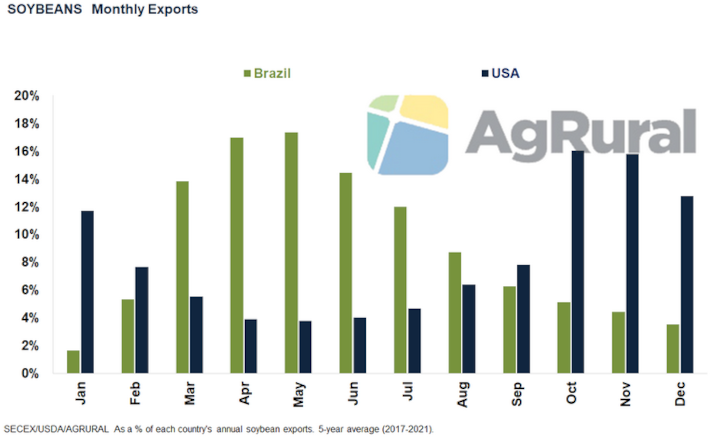

According to Brazilian customs data, accumulated exports from January to October 2018 were at 74.4m tonnes. As Brazil normally exports little soy in the last months of the year, when the US is the most competitive origin, the 76m tonnes estimated for 2018 seemed to be something perfectly doable. Despite all the tightness, the supply and demand table would make sense.

Trade War

The problem is that trades for shipment in November and December 2018 were happening all the time and involved too large volumes for exports to end the year at just 76m tonnes. China and the US were in a trade war and the Chinese, ready to show their strength, drastically reduced their purchases of US soybeans, turning to any and every alternative origin to meet their huge demand. Brazil, of course, was the obvious option. But there was a serious supply limitation. Even with record production, it didn’t seem possible to export more than 76m tonnes.

Nevertheless, the Chinese offered higher premiums to source the remaining soybeans that still existed in Brazil, raising offers at Brazilian ports to as much as USD 2.60 per bushel over Chicago – a new record-high at that time. In the end, the Brazilian “leftover” was not that small. In November and December 2018, Brazil exported 4.8m and 4.1m tonnes, far above normal for those months. As a result, the year ended with 83.3m tonnes exported.

Playing With Numbers

In early December 2018, Conab had raised its export estimate from 74m to 82m tonnes. Production, however, had been kept unchanged, at 119.3m tonnes. Even the USDA, at that time, was still working with 120.3m tonnes, a way too small production to support such a large export number.

In order not to implode the supply and demand table, Conab also used its December monthly report to reduce domestic consumption numbers since the 2012-13 crop, inflating the ending stocks of all the following seasons. That resulted in beginning stocks for the 2017-18 crop large enough to make possible the 82m tonnes estimate for exports and ending stocks of 1.6m tonnes.

But in January 2019, when Brazilian customs confirmed that exports had totalled 83.3m tonnes, Conab’s recently changed supply and demand table was useless again, and the agency stopped publishing that kind of estimate for soybeans. Conab only resumed its supply and demand projections in late 2021, but without historical data, and things remain like that since then.

More Production

During that period in which Conab didn’t release supply and demand numbers for soybeans, the agency made deeper adjustments to its numbers, including a review of the production size in five past crops. Even so, doubts remain and there are questions about Conab’s estimates for soybean crush, for example. After its monthly report was released in early August, the agency was criticized because, by assuming IBGE figures for the 2021-22 season beginning stocks, it reduced the 2020-21 crush – a number that, in theory, is informed by the industry and was already consolidated, with no possibility of revision at this point.

This is not about criticizing Conab’s methods, because I don’t know them in depth and because I recognize that the agency plays more roles and performs more tasks than would be expected with the resources at its disposal. And it was not just Conab that made mistakes in 2018. Other public agencies and private consultancies were also wrong, as everyone used to leave the past crops behind as soon as the new crop was planted. It took a very strong consumption season for the problem of underestimated production to surface.

Quarterly Stocks

It’s totally fine to revise production estimates. The USDA does that with the US crop when the Sep 30 quarterly stocks report suggests that production was larger or smaller than estimated. And that happens almost every year. With consolidated figures for domestic consumption, exports and stocks, it is easy to find the error: it is in the production estimate, which is then adjusted. And these USDA adjustments are made right at the end of each crop, not months or years later, when the size of a particular crop no longer influences the soybean market.

In Brazil, the IBGE makes semi-annual surveys of physical stocks. Although helpful, they are published several months after the reference date and often don’t match the production figures estimated by IBGE itself and the consumption data from Abiove or Conab, for example. The USDA also estimates ending stocks for Brazil, but they refer to Sep 30, the end of the world trading year used by the department, and are of little use because Brazil’s marketing year ends on Dec 31.

Satellite

Brazil’s soybean production and its supply and demand table will probably continue to cause surprises for a long time to come. And not because the planted area is underestimated, as some believe. It is very difficult to distort the size of the area at a time when surveys are carried out by satellite and there is relentless surveillance by environmentalists and importers. Surprises will continue to happen simply because it is necessary to carry out more frequent and efficient stock surveys, in order to fine-tune, in a timely-manner, the production size estimate via consumption and stocks, as happens in the USA.

Dashboards that may be of interest…