Opinion Focus

- Ukraine’s national seed bank, where seed samples are contained, has reportedly been damaged during the Russian invasion.

- Given the critical nature of seed banks to global food supply, this could have disastrous consequences.

- But there is a failsafe located 800 miles north of the Arctic Circle.

One of the consequences of the Russian invasion of Ukraine is the threat to seed banks. But what are seed banks, and why are they so critical for global biodiversity – and potentially the future of our species?

Why Do We Need Seed Banks?

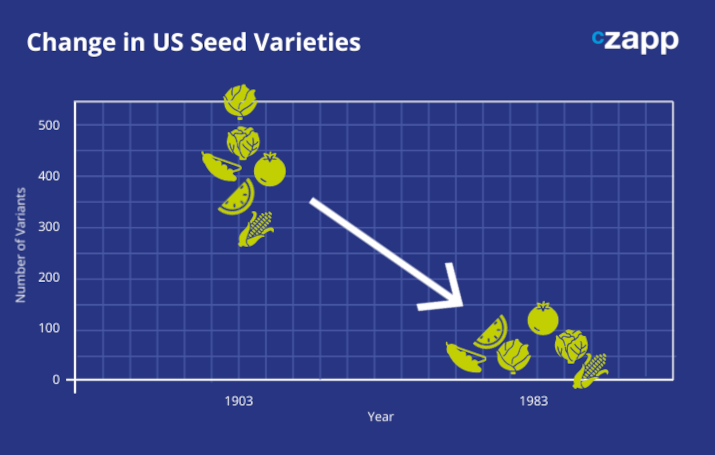

Once upon a time, there were thousands of varieties of each seed. Much like humans and other animals, plant species grow and evolve to adapt to changes in their environments.

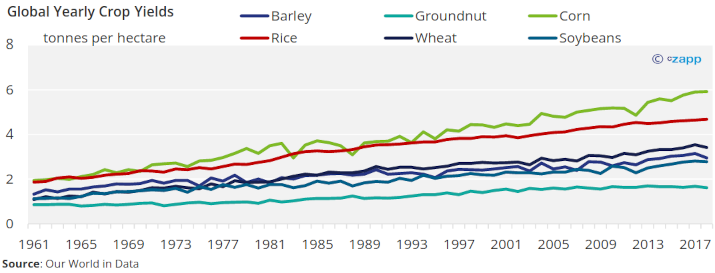

Often helped by human intervention, plant species over the years have been able to preserve some of the traits that protect them, such as resistance to drought or disease. As a result of plant breeding, farmers have been able to increase wheat yields by 15% in the past 15 years, which not only helps feed a growing population but also keeps costs lower.

As the world population grows, more importance is being placed on crops that can yield more, resist pests and survive weather abnormalities. But some valuable traits have been lost.

What Are Seed Banks?

Just because one characteristic is stronger than another at one point in time, that will not necessarily always be the case. For example, global temperatures are changing each year due to climate change. Crops growing in a normally temperate climate may need to become hardier to resist increased prevalence of drought, hot weather or pest.

But if we have lost these traits, how can we get them back? The short answer is that we can’t, but seed banks mean we shouldn’t lose too many more.

Scientists can find various crop breeds within these seed banks to crossbreed species and constantly improve yields or enhance resistance, protecting global food supply against changes in weather, rainfall or disease.

This is especially vital today. Around 60% of all calories consumed worldwide come from just four crops: rice, wheat, corn and soy. That means our ability to keep yields high is critical to our ability to survive.

Where Are the Seed Banks?

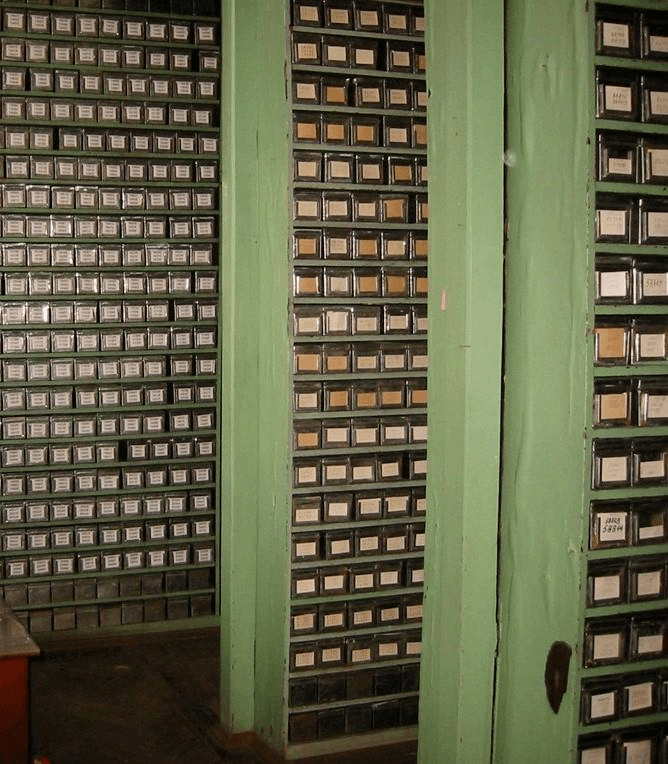

The first seed bank was established in St. Petersburg, Russia, named after Russian plant breeder Nikolai Vavilov.

Photo credit: Dag Terje Filip Endresen/Flickr

Today, it contains hundreds of thousands of seed specimens across different plant breeds – a vital effort that is crucial to continued plant diversity and yield.

Photo credit: Dag Terje Filip Endresen/Flickr

Different seed banks can specialise in different crops. The International Center for Tropical Agriculture in Cali, Colombia houses cassava, forages and beans, while the International Potato Center in Lima, Peru preserves potatoes.

Nigeria’s International Institute for Tropical Agriculture protects varieties of groundnut, cowpea, soybean and yam and the International Rice Research Institute in the Philippines is home to around 5,000 rice varieties.

The largest seed bank in the world is the Millennium Seed Bank Project, which obtained the Guinness World Record in March 2021. It is managed by the Kew Royal Botanic Gardens in the UK and holds more than 2.4 billion seeds.

How Are Seed Banks Protected?

There are now more than 1,500 seed banks globally but as we have seen recently, global conflicts can jeopardise the integrity of the facilities.

The National Centre for Plant Genetic Resources of Ukraine located in Kharkiv has collected over 150,000 specimens, but some have been reportedly destroyed as a result of the Russian invasion. This is one reason why a global safeguard has been developed.

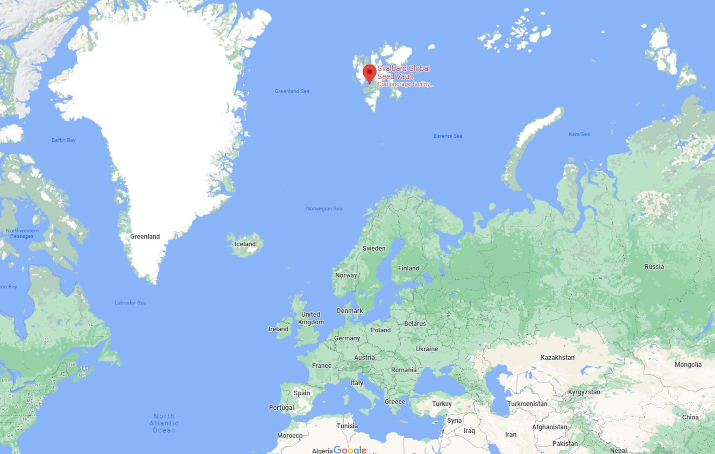

The safeguard comes in the form of the Svalbard International Seed Vault, located on the Norwegian island of Spitsbergen about 800 miles north of the Arctic Circle. It is also known as the Doomsday Vault.

This seed bank is not an ordinary seed bank. It operates under a “black box” arrangement, which means its stewards should never open or test any of the samples. It serves as a back up vault holding samples from countries all around the world. No single entity possesses all the codes for access.

The building is designed to last forever, built 130 metres into the rock at 130 metres above sea level. It measures 1,000 square metres and has the capacity for 4.5 million seed types.

Photo Credit: Einar Jørgen Haraldseid/Flickr

The vault has come in useful during previous conflicts. During the Syrian Civil War, the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas was unable to access its vault located within the country. It was able to withdraw some of its samples from Svalbard to regenerate seeds in Lebanon and Morocco.

The National Centre for Plant Genetic Resources of Ukraine joined the agreement and shipped seeds to Svalbard in 2009. In the seed vault’s 2021 progress report, it notes that Ukraine currently has 2,782 samples stored in the vault.

This means that, even if the seed bank in Kharkiv is compromised, some of its contents can be preserved. However, it is worth noting that Svalbard holds just a small proportion of the seeds in the national bank.

Concluding Thoughts

- Plant breeding bears great responsibility for our ability to feed our growing population.

- Yields have increased significantly since breeding began.

- The ability to breed crops is dependent on availability of a large variety of species.

- Seed banks allow crop diversity to continue and play a vital role in feeding the planet.

- While the invasion of Ukraine and potential destruction of the seed bank would be disastrous, all is not lost.

- A global safeguard exists in the form of the Doomsday Vault, which contains a huge catalogue of seeds from around the world.