Insight Focus

- Russian sugar production will be the largest in 3 years.

- This is despite partial mobilization of the workforce.

- Russia remains dependent on foreign beet seeds.

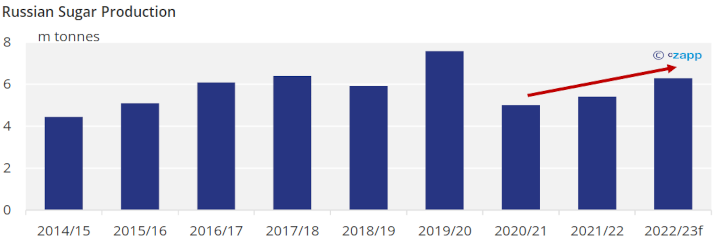

The 2022/23 Russian sugar crop is shaping up to be the largest in the last 3 years, returning to 6m+ tonnes production for the first time since the record 2019/20 season.

This is despite the ongoing invasion of Ukraine. Partial mobilization of the workforce and sanctions don’t seem to have had a major impact on sugar production yet, with more than 90% of the beet harvest complete.

Poorer Regions Harder Hit by Mobilisation, Sugar Too?

Forbes estimated in October that around 0.7m people (mostly men of fighting age) fled Russia to avoid being called up in September’s ‘partial mobilisation’ of 300k troops.

Around 500k citizens and residents had already left Russia since the start of invasion.

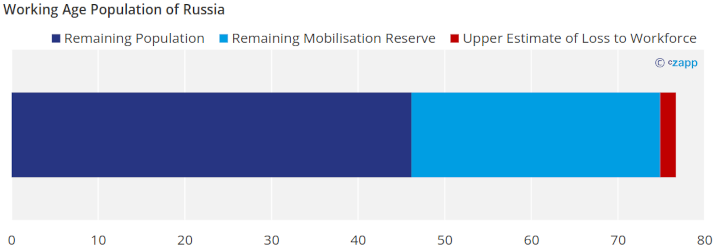

Adding in an upper estimate of those wounded or killed in combat of around 300k men means there could be as many as an additional 1.8m working aged people removed from Russia’s workforce since March.

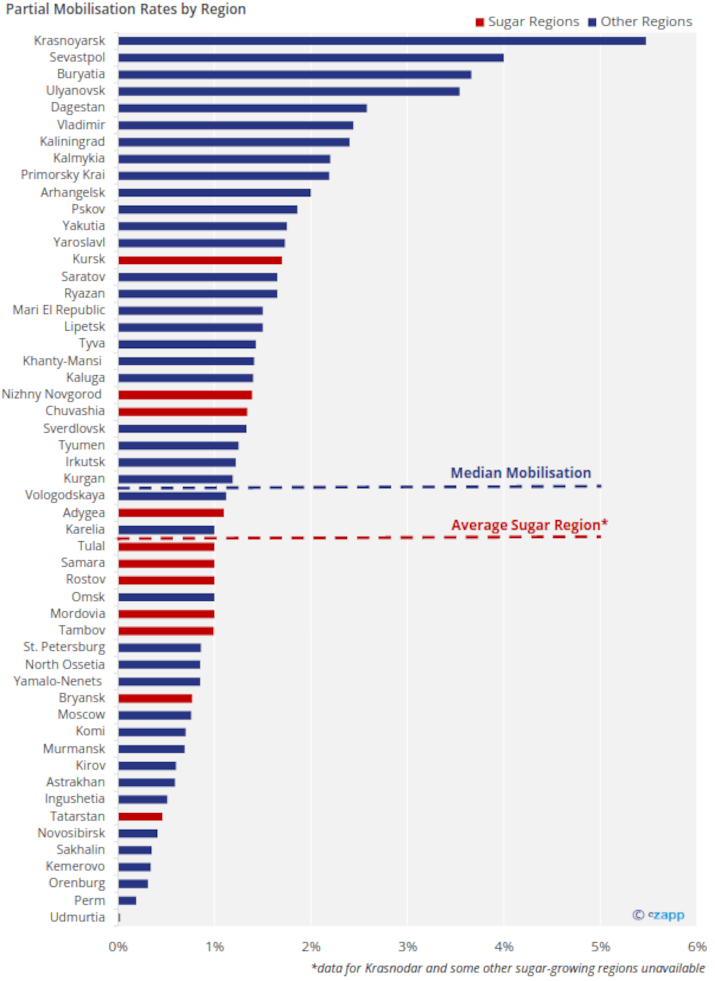

We had wondered if the agricultural sector would be more badly affected since mobilisation was coordinated at the regional government level.

Authorities in richer, urban regions would not want to risk protests and so tended to be lighter on recruitment than in poorer, rural regions where risk of dissent is lower.

According to mobilization data captured by Independent Russian news outlet Important Stories, we think regions where sugar beet is grown faced slightly lower rates of mobilisation than the overall median rate, 1.1% vs 1.2% nationally (though data is unavailable in some sugar-growing regions, namely Krasnodar).

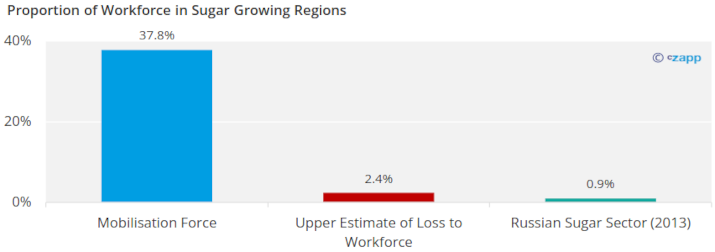

This would amount to 70-90k men mobilised from these regions, and assuming the same rate as nationally, up to a further 350k emigrated or involved in combat. Combined this could be as high as 2.4% of the workforce in these regions.

For reference, in 2013 the FAO estimated the entire sugar sector at around 200k people, just under 1%.

This could suggest that the sugar beet industry may not have been disproportionately affected by mobilisation.

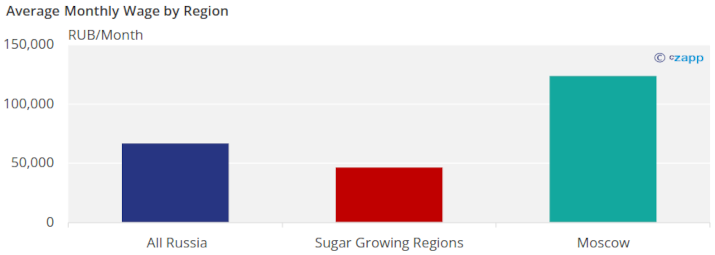

This is despite the national average wage in these regions being 70% of the national average 66,500RUB per month.

Source: Rosstat

A secondary problem caused by large-scale emigration and mobilisation is a drain on industry-critical personnel.

Unlike other countries like Finland and Sweden, Russia has no formal plan to ensure that in the case of war, key sectors like food production are protected from mobilization.

Reports from grains farmers have indicated the mobilisation of combine harvester operators delaying harvests. More troubling are reports of empty farms after farmers were mobilized, leaving crops unmanaged.

However, with limited reports of disruption to the 2022/23 sugar crop perhaps this industry avoided the worst of the effects.

Longer Term Reliance on Foreign Beet Seeds?

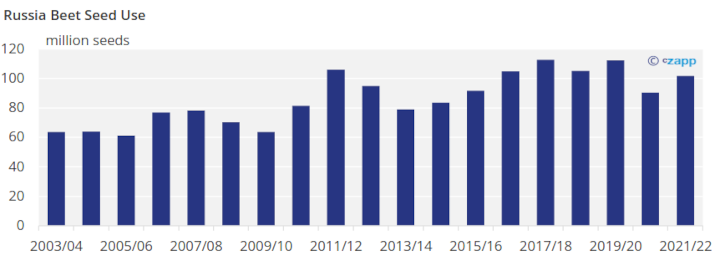

Aside from labour shortages, whilst Russia is generally self-sufficient in sugar now, we think at least 95% of Russia’s sugar beet seeds comes from Europe and the United States.

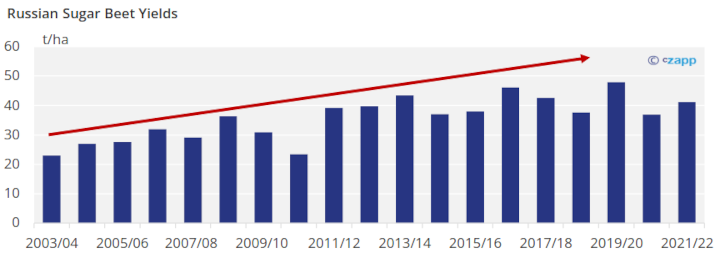

These modern sugar beet seed varieties will have helped Russia’s sugar beet yields to double in the 21st century, alongside investments to farm equipment and technology.

Since seeds are used for food production, they are not covered under current sanctions. Russia can continue to import the sugar beet seeds provided suppliers are still willing to sell and Russia can continue to pay.

Corteva, a major global seed and crop protection supplier announced in May that it was withdrawing from Russia and Belarus, other voluntary withdrawals by western companies will likely hurt food security without need for sanctions.

Russia’s agriculture ministry proposed earlier in the year the introduction of import quotas, forcing the domestic industry to ramp up development and production of home-grown seeds.

It is unclear whether this proposal will gain traction, however it would initially leave Russia heavily dependent on soviet-era seed varieties which will be far less productive and resilient than modern alternatives.

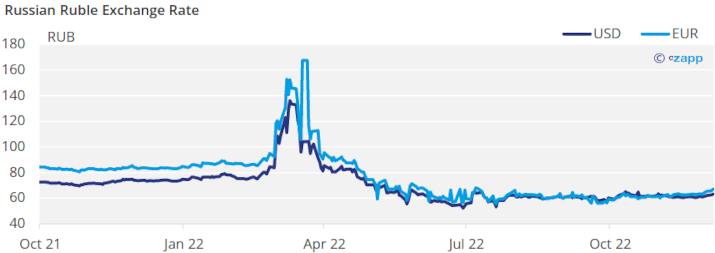

One plus for Russian growers in the short term at least is the cost of foreign currency. Falling imports and good capital control by the Russian central bank has meant that the Ruble has since been one of the better performing currencies this year, appreciating to around 60RUB/USD after starting the year closer to 80RUB/USD.

Massively scaling up their domestic industry will likely be an enormous challenge, from both development of modern seed varieties to ramping up production to meet domestic demand.

Thus, we think Russia will likely be heavily dependent on foreign imports for at least the next few seasons, at least if we do not see a severe escalation of the war in Ukraine.