Insight Focus

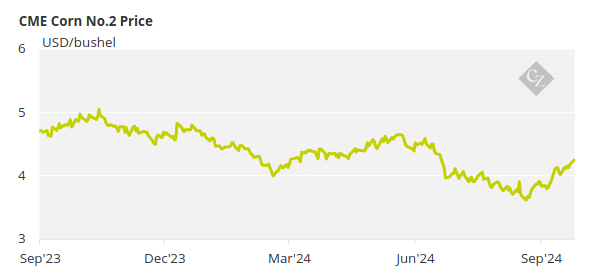

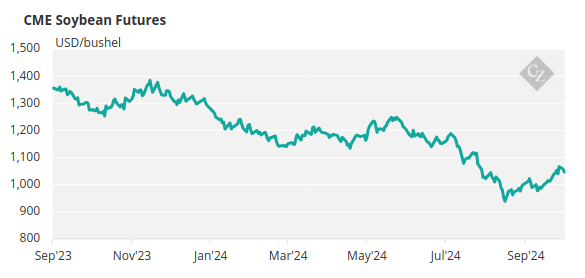

Global soybean and corn prices are finally beginning to rise. This is due to concerns about the climate in Brazil. However, pressure is still coming from the success of the 2024/2025 season in the US, which is already in the harvest stage, and by the good results of the 2023/2024 crop in South America.

An earlier dry season and high temperatures in Brazil is beginning to lead to concern over the country’s soybean and corn crops. After a succession of falls since the end of 2023, the Chicago corn and soybean futures prices have both now started to rise.

Climate Reminiscent of 2021

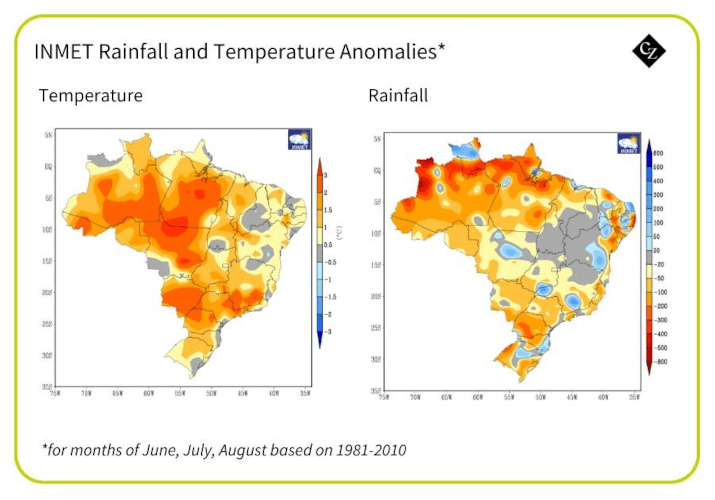

Since August, more than half of the country has experienced significantly higher temperatures than the historical average, with increases ranging from 3°C to 5°C. This, combined with a lack of rainfall, has left the soil in producing regions in need of even heavier rains for the proper development of the crops.

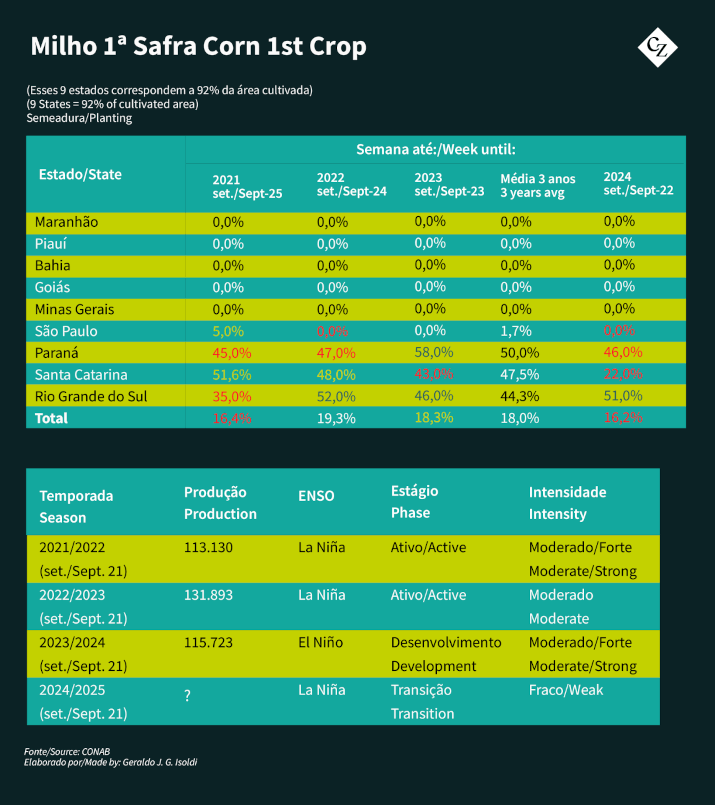

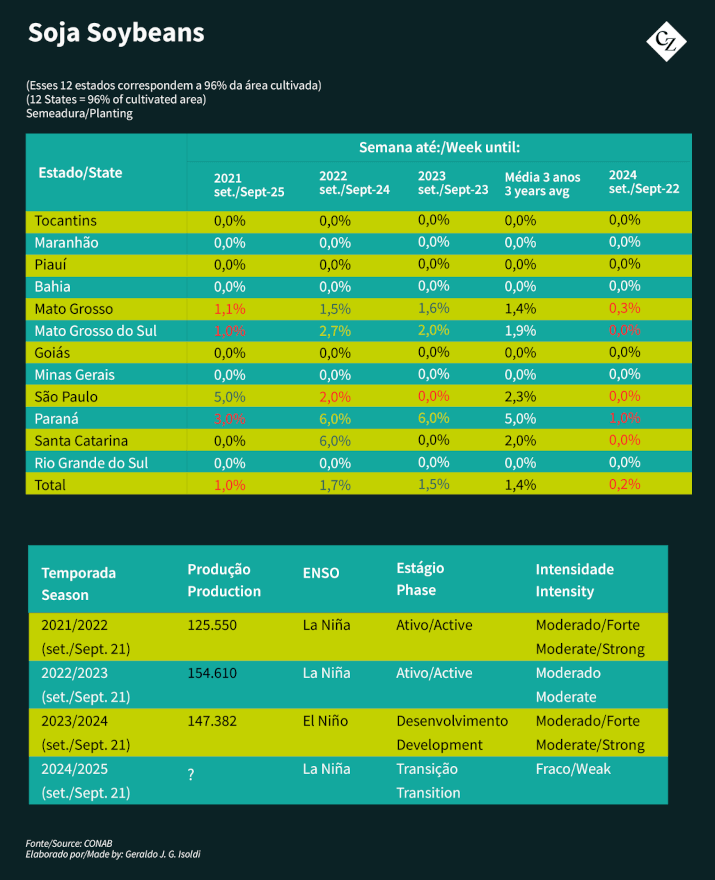

The climatic pattern in Brazil in September of this year is like that of September 2021, albeit with some nuances. In September 2021, Brazil began to feel the effects of a moderate La Niña, resulting in droughts in the south and above-average rainfall in the north and northeast.

Similarly, in September 2024, we are in a neutral phase, but with the expectation that a new La Niña will start to form between October and December. Therefore, the weather also exhibits transitional characteristics, with the possibility of droughts in the south and rainfall patterns in the north and northeast as soon as La Niña establishes itself.

Planting Pace a Cause for Concern

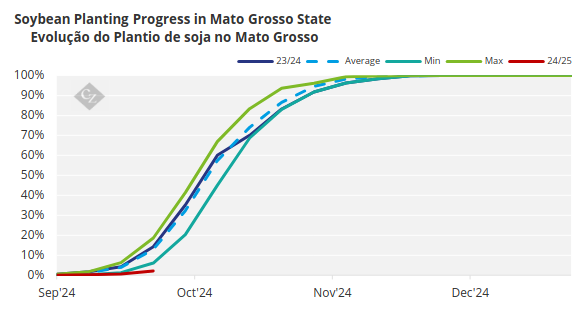

In both periods, the pace of corn planting is quite similar. However, for soybeans, which are traditionally still in an early stage, the 2024 planting is considerably delayed compared to 2021, although both are below the historical average.

For both crops, the result has been the worst harvest in the last three seasons. However, the corn crop cycle is longer than that of soybeans, as about 80% of total corn production comes from the second “safrinha” crop, which begins planting in January. The delay in soybeans, in turn, places the second corn crop at a greater risk of adverse weather conditions.

Another factor causing delays in planting is the reluctance of farmers to put their machines in the fields. According to the Planting Report from IMEA, as of September 13, only 0.27% of the planned area had been seeded, compared to 1.82% at the same time last year and a historical average of 0.84% for the period.

The Brazilian authorities each year determine the “sanitary fallow” season, which is the period when farmers should abstain from planting certain crops to interrupt potential cycles of pests and diseases that affect crops, such as Asian rust in soybeans. In Mato Grosso, soybean planting has been allowed since September 6, but producers remain hesitant.

So far, the productive potential of the crops has not been affected by the weather. However, corn and soybean prices are expected to remain supported by speculation surrounding Brazilian weather until rainfall normalizes—or does not—by mid-October.

The Dynamics of Rainfall in Brazil

The dry season in Brazil began a little earlier this year, but rainfall during the winter is rarely enough to offset the high rate of evaporation. It is common to start the new rainy season with concerns about drought and potential production problems for the upcoming crop.

Seasonal rains typically begin in Brazil’s Midwest at the end of September, expanding to other production areas in October. Rainfall at the end of September tends to be sporadic and light. Soy planting at the start of the season benefits more when the initial rains occur as expected or even earlier, although it is common to have to wait for significant rains until mid-October.

The earlier the pre-season rains and storms begin, the faster soybean planting can progress. The best years for corn and soybean production usually occur when these rains start early and are consistent, which is not happening in the current season.

The rainfall at the end of September will not be enough to correct the dryness in the topsoil layer, and producers will have to wait for a significant increase in precipitation for fieldwork to pick up pace. According to the meteorological consultancy World Weather, as of September 26, the northern part of the state of Mato Grosso and many of the cultivation zones in the South-Central region of Brazil may benefit from some rainfall in the first week of October.

However, this rain will still not be enough to reduce the water deficit in these areas. As a result, planting in Brazilian soils is expected to remain delayed, at least during the first half of October. This is the same period when, according to CONAB, 30% of the first corn crop and 19% of the soybean crop had already been sown last year.

Source: IMEA

According to World Weather, the La Niña phenomenon cannot yet be considered responsible for the delay in the rainy season in Brazil, but the comparison with the 2021/2022 season is unavoidable. Currently, we are in a transition state from ENSO-neutral conditions to the emergence of a new La Niña. At this moment, neutral conditions prevail, but there is a significant chance (71%) that La Niña will develop between October and December 2024 and persist until early 2025.

Wind and ocean temperature patterns indicate that this phenomenon may begin to strengthen, evidenced by the cooling of waters in the central and eastern Pacific, along with the strengthening of trade winds, typical of La Niña.