Insight Focus

- The shipping industry currently uses about 300 million tonnes of fossil fuels.

- Something must change if the industry is to meet its strict environmental targets.

- Could biofuels be the marine fuel of the future?

The Food vs Fuel Question

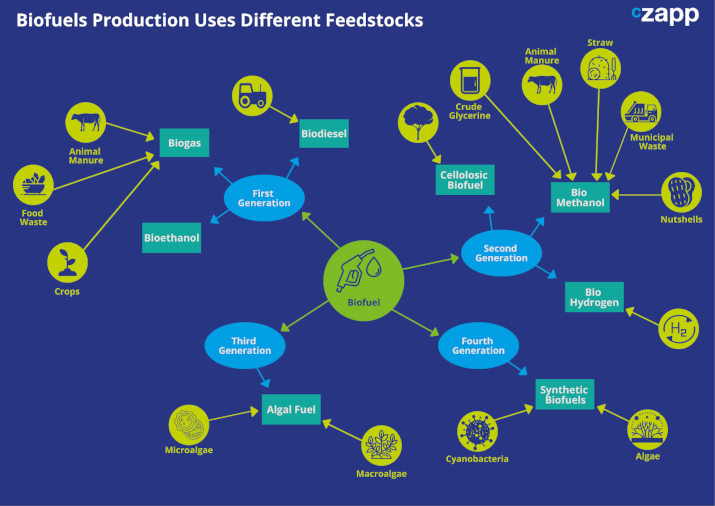

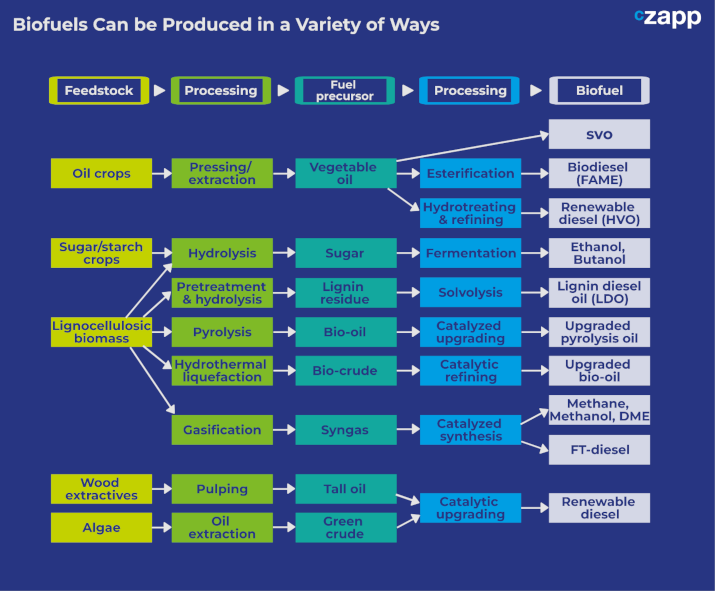

Biofuels are often seen as an extremely green and versatile fuel. They can be produced by a variety of different methods but the most established process derives biofuels from crops – namely corn, sugarcane and sugar beet.

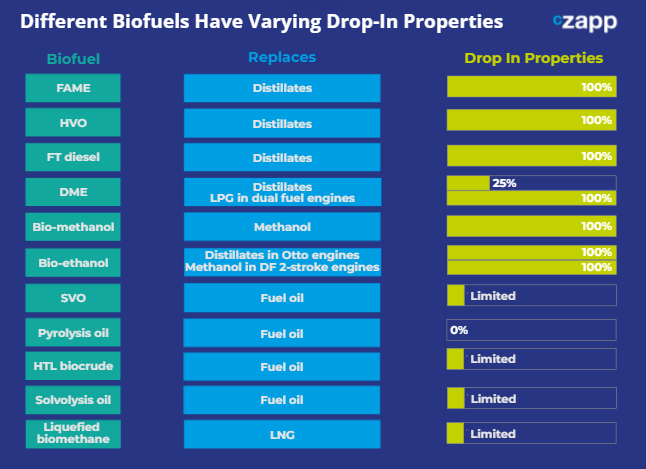

Depending on the type of biofuel and its production process, it can be used as a drop-in fuel, which means no modifications are required to engines. It can be used in all ship types and sizes.

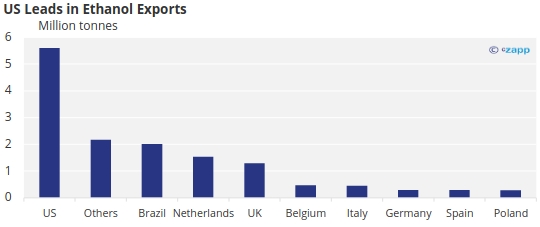

It can contribute to a circular economy since it can be produced using food and animal waste. This also means that it is the countries with the most established agricultural sectors that are the biggest biofuels exporters.

Source: UN Comtrade

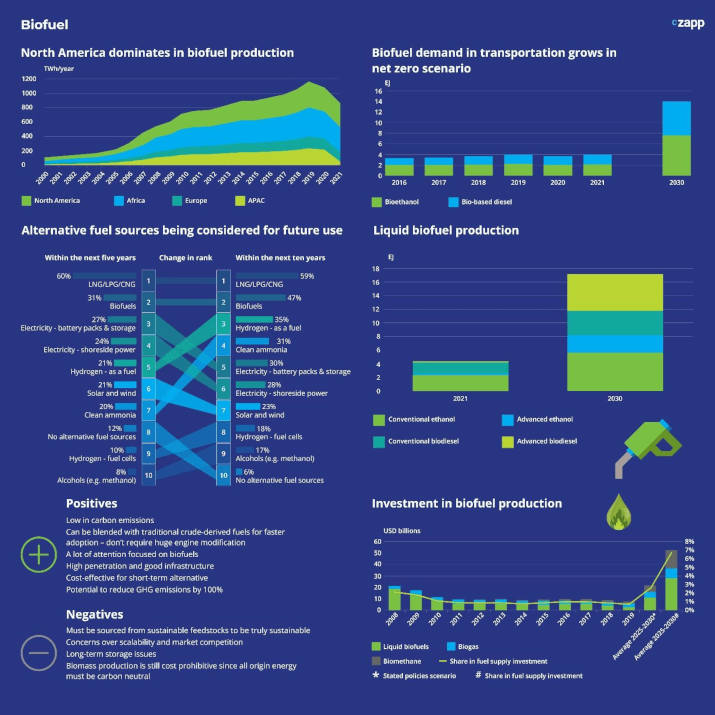

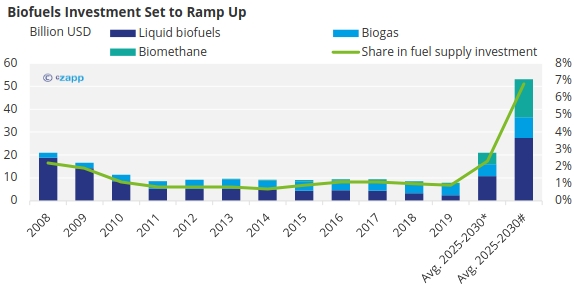

There is already substantial investment in biofuels. Large sugar producing countries Brazil and India have created policies that promote biofuel production, which will remove a certain quantity of sugarcane from the food supply chain.

*Stated Policies Scenario

#Sustainable Development Scenario

Source: IEA

But this is one of the biggest issues faced by biofuels. The fact that biofuels come from consumable crops presents some sustainability concerns. (food security – rising food prices)

Many argue that priority should be given to biofuels produced from forestry residues, lignocellulosic crops, agricultural residues and manure rather than food-based crops.

Source: IEA

Technology, Pricing at Different Stages

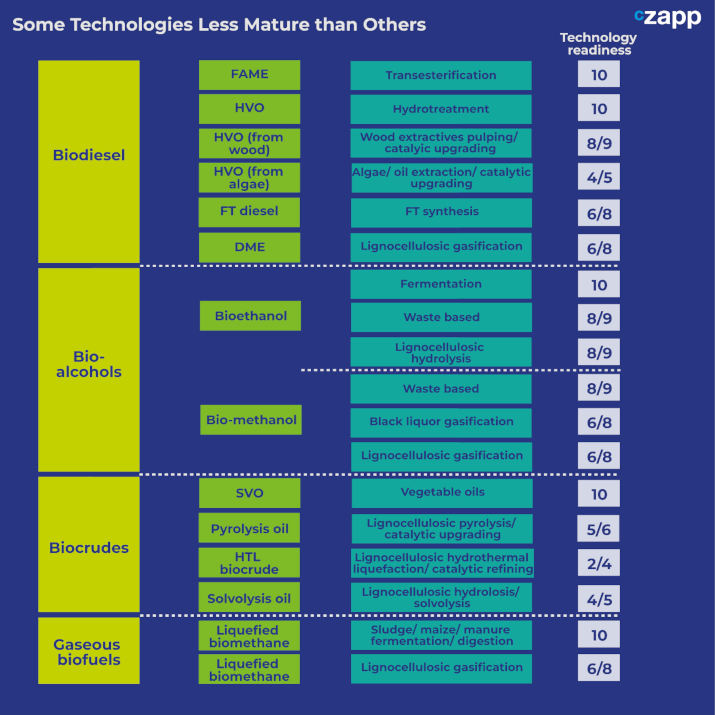

Biofuels produced from crops are known as conventional biofuels – or first generation. Those produced from other materials are known as second generation or advanced biofuels. Predictably, the first-generation fuels are more mature.

Source: EMSA

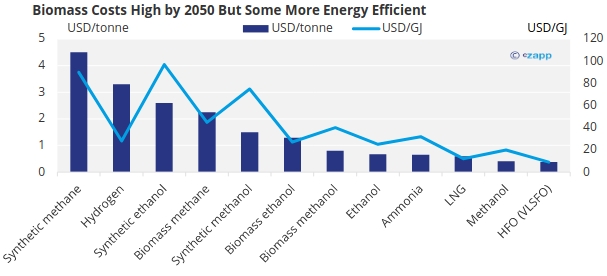

Despite this, there is a transition in production pathways toward more advanced feedstocks that do not involve removing capacity from food production systems. But higher cost is an obstacle. The costs of some biofuels is higher than other fuels on a USD per tonne basis, although some can be more efficient on a USD per Gigajoule basis.

Source: IMO

In terms of pricing to 2050, the European Maritime Safety Agency says the total cost of ownership for HVO and FT diesel ships is comparable to or lower than VLSFO vessels. Costs of bio-methanol vessels are likely to be level with VLSFO by 2050 while FAME lies a little higher on the cost curve but may be priced comparably to VLSFO.

The agency added that price fluctuation of fossil fuels or other market measures could close these pricing gaps further.

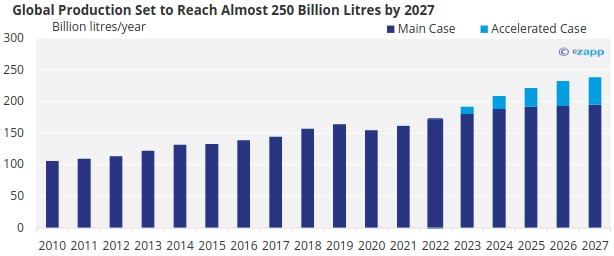

Production Grows… But So Does Consumption

Biofuels production is already relatively developed. The speed of scale up means there is opportunity to replace a great deal of fuel oil, although the volumes produced commercially at the moment would not be sufficient to replace conventional fuels in shipping vessels.

Note: Biodiesel, ethanol & renewable diesel only

Source: IEA

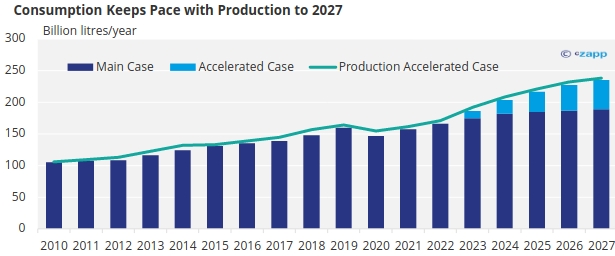

But consumption is also growing in line with production and a sudden surge in demand from the marine industry may knock out the balance, which would inevitably push up biofuel prices.

Note: Biodiesel, ethanol & renewable diesel only

Source: IEA

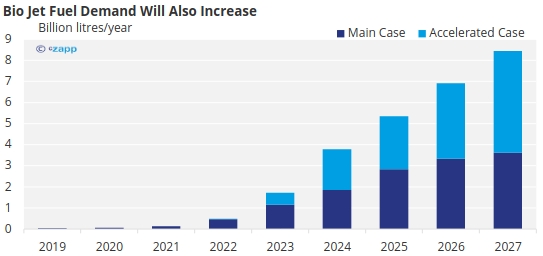

And this does not account for increased demand from other sectors. Demand for bio jet fuel is also set to increase to 2027 and, as the drive to reduce emission continues, this demand will increase exponentially.

Source: IEA

Bio jet fuels are currently made from vegetable oils. However, as EVs become gain more of a foothold in the road transport sector, some of the oleochemical biofuels currently used in the sector could be diverted to the marine and aviation sectors.

In other sectors, woody biomass is mainly used for heat and power production. However, the IEA says the use of biomass for heat power is expected to drop in the medium to long term in favour of more renewable energy sources. This could then create more capacity for marine fuel.

Another consideration is that biodiesel is also about 8-10% less energy dense than low sulfur diesel. This means that slightly more than 300 million tonnes of biodiesel would be needed to fully replace fuel oil, increasing the need for bunkering and increasing voyage times as a result.

Emissions Depend on Feedstock

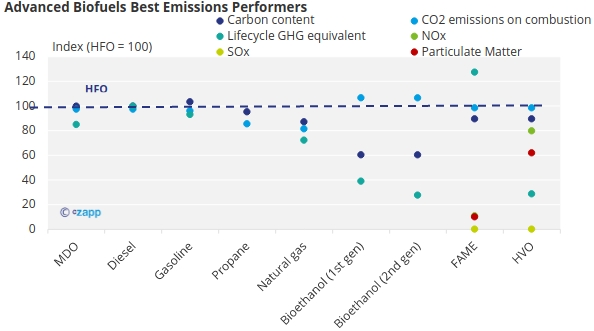

Biofuels have the potential to reduce well-to-wake greenhouse gas emissions. In fact, advanced biofuels can even reduce these emissions by up to 100% if combined with carbon capture technologies.

Most biofuels are free of sulphur, and NOx emissions and particulate matter is greatly reduced compared with HFO.

Source: EMSA

But while biofuels are generally considered a cleaner substitute for fossil fuels, there are some considerations to take into account. Firstly, biofuels production can sometimes have a negative environmental impact when it comes to biodiversity loss and carbon stocks.

Secondly, lifecycle emissions can vary greatly depending on the feedstock used to produce the biofuels. For example, the impacts of land use change can cancel out the positive effects of biofuels produced using food and crops. And while there are moves to shift from crops to waste and residues, we cannot automatically assume that these are automatically sustainable.

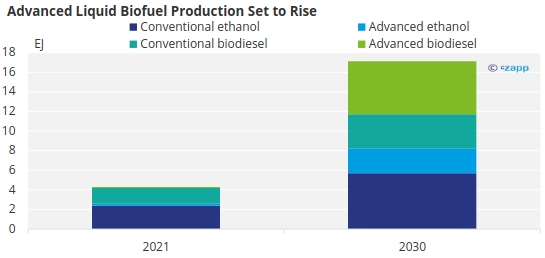

Advanced biofuels have more emissions reduction potential but are obviously less developed. Their development still requires substantial investment. Advanced biofuel production is set to rise.

Source: IEA

Another characteristic that should be considered is the lubricity of the fuel, which is a measure of its ability to reduce friction. While FAME lubricity is good, that of HVO is relatively poor, meaning additives may be required. This implies additional costs and potentially less emissions savings.

But storage stability of FAME is poor, meaning antioxidants may be needed or more frequent bunkering may be required. In contrast, the storage stability of HVO is good. This stems from a lack of long-term fuel testing data for marine biofuels.

While there is a lack of clear regulations for biofuels in the marine industry, the drop-in nature of many of the fuels implies transferable regulations from fossil fuels to their biofuel alternatives. This however requires more clarity.

But more shipping companies are dipping their toes into biofuels. Biofuels provider GoodFuels recently helped Spar Shipping and Norden bunker 1,100 tonnes of biofuel in Rotterdam for voyages to Africa and Asia. Hyundai GLOVIS also refuelled its Glovis Sunrise vehicle carrier with 500 million tonnes of a biofuels blend.

Concluding Thoughts

- Biofuels are a strong contender for the marine fuel of the future.

- They produce low levels of well to wake emissions and particulate and have favourable drop-in qualities.

- The provide a good solution to lower emissions without requiring major infrastructure investment.

- However, some issues still need to be addressed, such as lifecycle sustainability.

- As global food prices continue to rise, governments could shy away from using crops for biofuel feedstocks.

- While reliance on the currently available biofuels is a good short-term solution, the focus needs to be on reducing barriers for advanced biofuels in the medium to long term.