Insight Focus

The Brazilian real (BRL) is projected to weaken against the US dollar, potentially reaching 6 BRL per USD. While the sugarcane crushing season has commenced at a rapid pace, sugar output has been somewhat disappointing thus far.

Click here to watch the full webinar!

Hi everyone, it’s Stephen from CZ with another update on the sugar market.

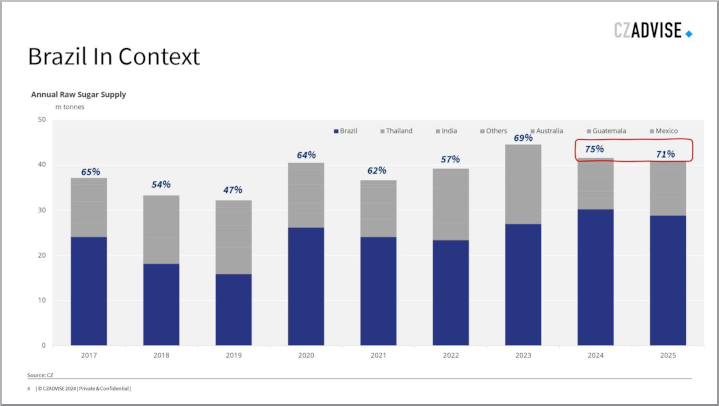

I thought it would be a good time to focus on Brazil. After all, it’s the world’s dominant sugar supplier this year so what happens in Centre-South Brazil is important for the market.

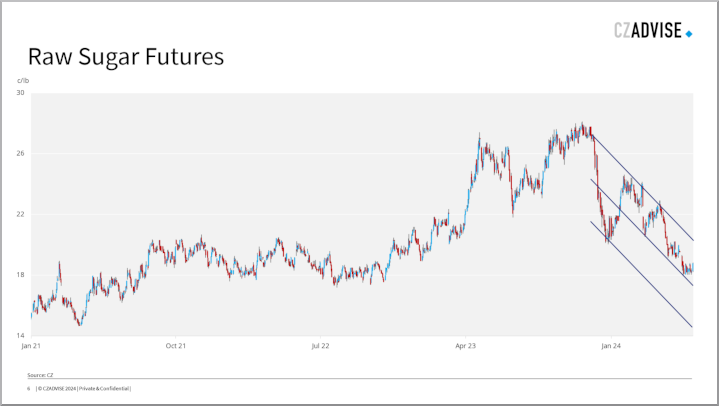

The current sugar bear market assumes that everything is going fine in Brazil. So let’s take a look. We’ll start with the currency and then zoom in on sugar and ethanol.

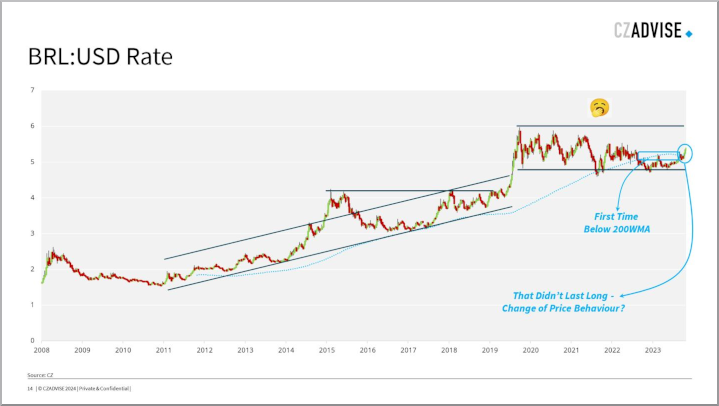

You can see from the chart that the 2020s have been rather dull for the Real. It’s traded between 4.80 and 6, which means it’s been stable after a decade of weakness in the 2010s.

However, for most of the past 15 years the BRL has been weaker than its 200WMA, that is to say it’s been weakening against the USD. In recent weeks it had strengthened below the 200WMA, which hinted that maybe we were going to get some form of major change in price behaviour. But we’re back above the 200 WMA and so it’s business as usual.

We’ve also had 5 consecutive months of BRL weakness for the first time since 2018. If June is another weak month that’ll be the first 6 in a row since 2014. It looks like it’ll stay between 5 and 6 for a while yet but I wouldn’t be at all surprised if it’s at 6 against the Dollar at some point in 2024.

This is important for Brazilian agri exports – a weaker BRL makes them more competitive on the world market and so all else being equal is negative for futures markets, including sugar.

So that’s the boring macro part over, let’s zoom in on the Brazilian cane harvest and check out what’s going on.

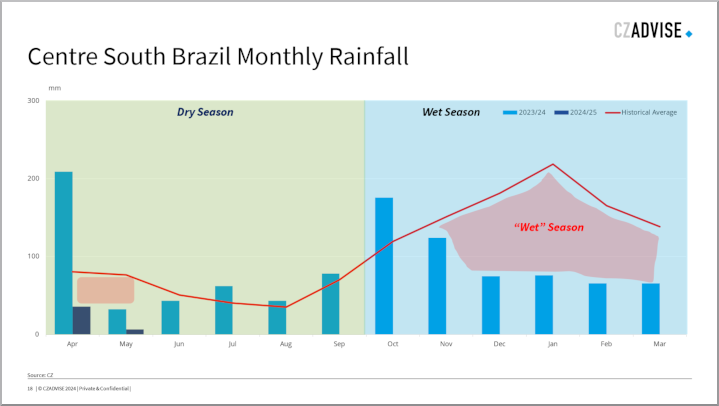

Here’s a chart of rainfall in centre south Brazilian cane regions in the past 15 months or so. You can see from the chart that CS Brazil has a dry and a wet season. However, the wet season that finished in March wasn’t very wet. Since November, rainfall has been much lower than the historical average. This has been great for shipping sugar out of Brazil, but less good for cane health.

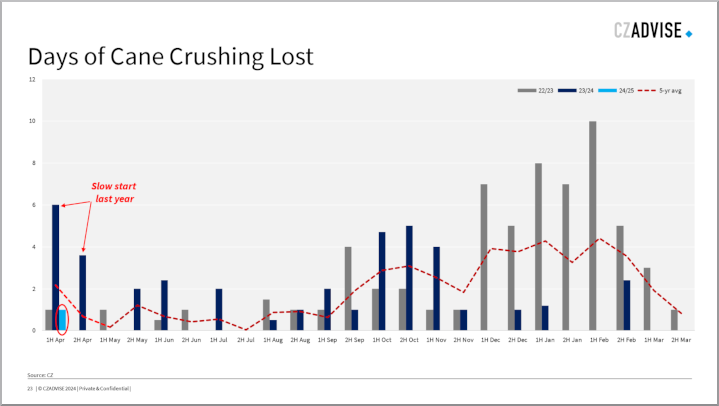

The dry weather has continued into April and May. As we will see, this has been good for cane harvesting, but it’s raising questions about the health of the cane in the fields. You can see that in the amount of harvest time the mills have lost due to rainfall.

This chart shows lost days by fortnight – you can clearly see the difference in wet and dry seasons here. We’ve had data to the middle of May and you can see mills have lost around 1 day of crushing operations so far this season. This is versus a 5-year average of 3 days lost by this time. Last season the industry lost nearly 10 days crush time in April and the first half of May. This makes year on year comparisons between last season and this tricky at this point.

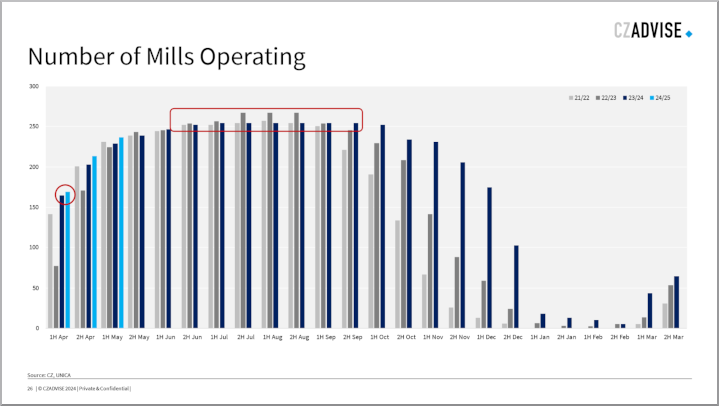

The number of mills operating is high too. 169 mills were crushing in the first fortnight of April, the most since the 2020 crush. This year we expect 260 mills to operate, up 6 on last year. So…already the weather has been dry and the mills are operating well.

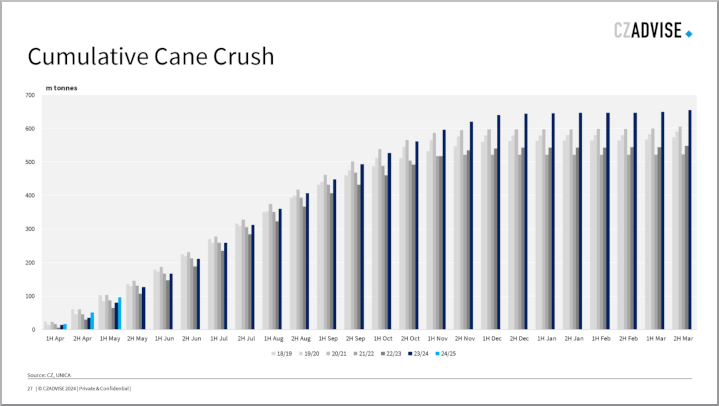

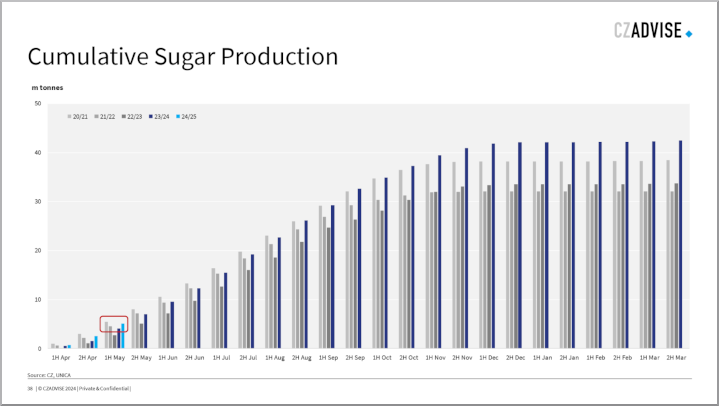

Put this together and the cane crush by mid-May was 95m tonnes, the best since 2020 and 10% above the 5-year average.

We’re already 15% of the way through the cane crush if our 610m tonnes cane forecast is right. Big if. You can also see that early crush data doesn’t really show you how much cane will ultimately be harvested – just look at last year’s slow start and final outturn. But getting ahead can’t hurt.

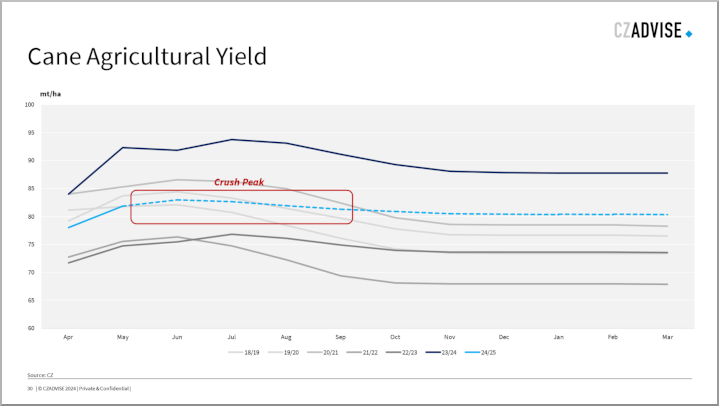

You might be wondering why we don’t think this year’s total cane will reach last year’s level. Firstly, as I mentioned before, it’s been dry and this may hinder cane development. Last year’s weather was amazing for cane development and so far hasn’t been repeated. This means we think ag yields won’t match last year’s stellar results, but will still be decent for Brazil.

Let’s see how they sustain through the peak of the cane crush.

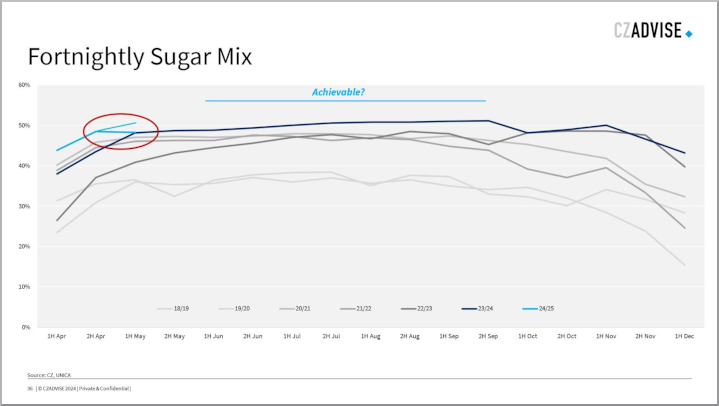

I was talking earlier about how quickly the mills had started crushing cane, and this is important because the sugar mix isn’t ramping up as quickly as most people had hoped.

As a reminder, many mills in the region can make sugar or ethanol from the cane and the relative amounts they make depend on the set-up of the mill and the prices of sugar and ethanol. The signal to the mills for months has been to maximise sugar output and they’ve been investing heavily in crystallization capacity.

We expect a record allocation of cane to sugar this year, at 52.5% of output. But we’re not seeing this come through in the stats yet. In 1H May the proportion of cane used to make sugar dropped on the fortnight, when it should be climbing. This was disappointing. We need to hope this was a one-off and that the next few weeks will continue the sugar ramp-up. Otherwise, the way the cane crush is going too much will have been harvested to reach the mix we’re expecting.

This requires a mix of 55% to sugar during the peak of the crush, so the pressure is on. And this year of all years, the sugar market is still highly dependent on Brazil for supply, at least until new European and Thai physical supply becomes available towards the end of the year.

This all means that sugar output to date is close to the highest we’ve ever seen to the first half of May, but this is largely due to the fast start in April and not because output is ramping up well today. This does need to change. 12% of the sugar we expect to be made has been made so far, but in several other seasons we’ve already been at 14 or 15% of the total sugar output by this stage. It sounds marginal, but when you’ve got stretch targets to hit and low global stocks these margins might matter.

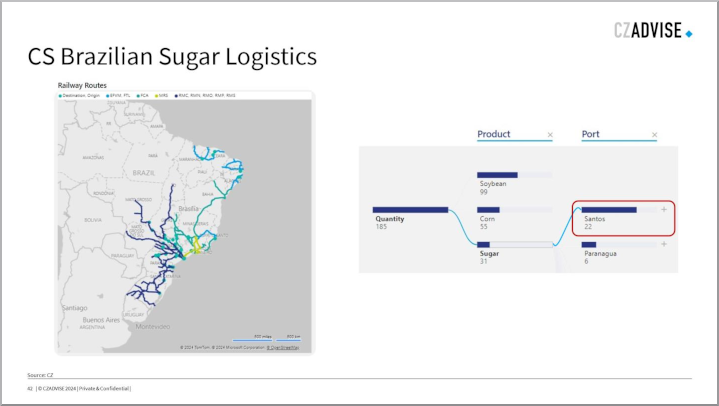

Now, it’s one thing to make this sugar, but it’s no use if it’s all up-country. What counts is getting it to the port and out onto the world market where it’s needed.

This is going to require a rapid flow of sugar to the ports and then onto vessels. For sugar, that port is predominantly Santos.

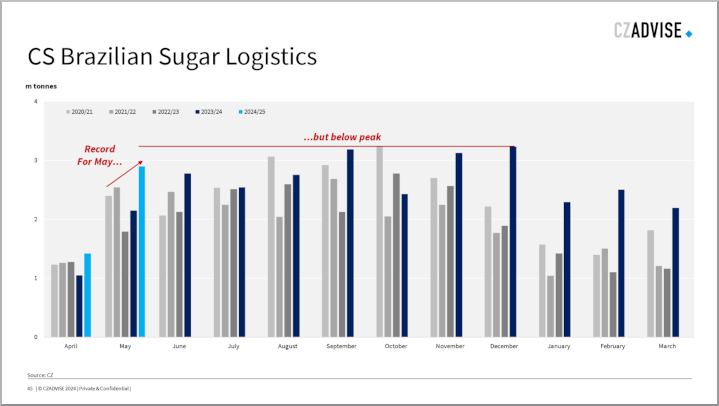

In May, 2.9m tonnes of raw sugar were exported from CS Brazil, a record for the month of May. This was an excellent performance and highlights strong global demand for sugar as well as Brazil’s good logistics performance too. But strangely enough, some of the commodity trade were a little disappointed by this figure.

The peak flow from CS Brazil in 2023 was around 3.2m tonnes a month, so you could argue that this year’s performance was 2 or 3 vessels below what’s possible.

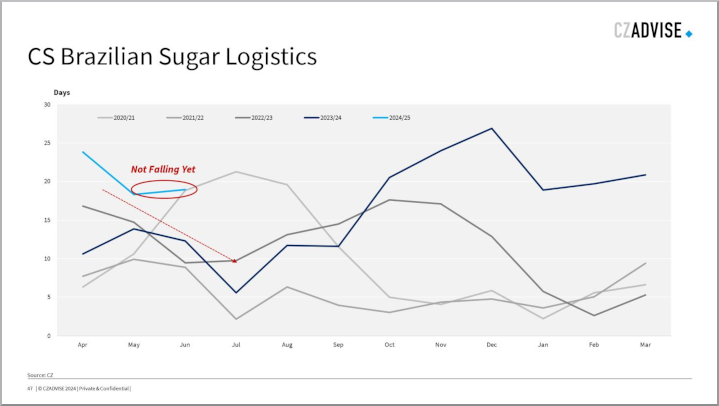

Certainly the demand for the sugar is still there. Vessels are waiting around 20 days to berth; it’s been this way since October and unlike previous years where the queue has dropped at the start of the crush, it remains. June and July Santos VHP is offered at a 30 point premium to the futures, with the July/October spread at flat.

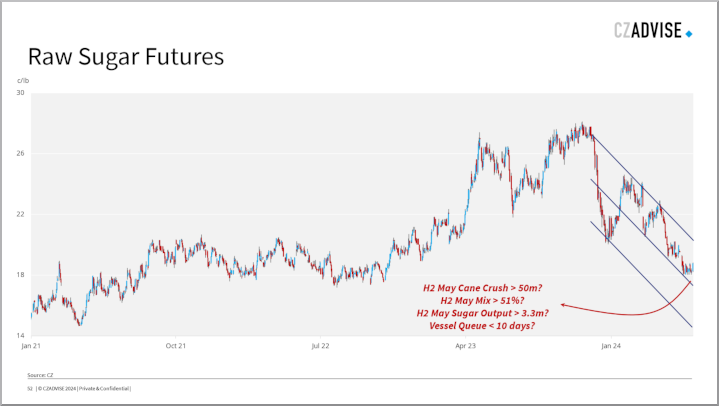

So if the current downtrend in sugar prices is to persist, what do we need to see? We need good weather for continued rapid cane crushing. We need mills to rapidly ramp up the sugar mix they are achieving.

I’d hope that cane crushing figures for the second half of May exceed 50m tonnes, with a mix of more than 51% and sugar output more than 3.3m tonnes on the fortnight. We also need local logistics to perform as well as possible, and for the vessel wait time to drop towards 10 days.

If this all happens, then the flow of sugar to the world market and the potential weakness of the BRL should push sugar prices lower.

That’s what you need to watch for in Brazil. Thanks for watching, and I’ll see you next time.