1,536 words / 7.5 minute reading time

- This season marks the first time GM cane derived sugar will be produced for commercial sale.

- Global restrictions on GMOs mean there could be disruption in the sugar markets if countries reject its imports, causing a supply shortfall at a time when food security is a major global worry.

- However, as sugar is a processed product that contains no genetic material, Brazilian producers have classified it as non-GMO and are hopeful it will be accepted by their major raws buyers.

A Brief Introduction to GM Cane

GM cane is sugarcane that has had its genome altered by the introduction of genes from another organism. These modifications aim to give the cane advantageous traits, such as drought tolerance or pest resistance.

The development of GM cane began in 2013, when a variety designed to better handle drought was produced in Indonesia. And now, Brazil’s major sugarcane research centre, CTC (Centro de Tecnologia Canavieira SA), are producing two varieties that will be become the first commercially available products, as part of this year’s Brazilian crop. Both are designed to combat cane borer; an insect pest that costs Brazilian cane growers around $1.5bn a year.

The varieties are altered to contain genes from a soil bacterium called Bacillus thuringiensis (or Bt). This allows the plant to produce proteins that are toxic to cane borer and act as an insecticide. Unlike most animals, insect pests have alkaline stomachs, so once eaten, the Bt protein reacts and turns into a toxic compound that kills the pest.

These proteins are completely safe in our acidic stomach and break down quickly in soil, meaning they don’t negatively impact our health, nor the environment. The toxicity to insects is also low, so a large volume of the plant must be consumed to kill it, allowing farmers to actively target pest species and minimise any ecological collateral damage.

This method of genetic modification has been used for over 20 years in crops such as maize, potatoes and cotton. It has seen boosted yields and drastically reduced insecticide use, making producers more cost efficient, whilst lowering their environmental impact.

For the new Brazilian crop, around 30k ha of the two GM varieties have been planted (roughly 2.5m tonnes of cane). With the current crop forecasted at 600m tonnes, this represents less than 1% of the total volume. However, despite this small volume, some see it as the first step towards the Brazilian sugar industry embracing GM technology. If the varieties are a success, farmers will likely use them to renovate their fields, increasing the area of GM cane and the volume of sugar produced from it. With new lines under production worldwide, the success of this crop, as well as how the sugar treated by importers, will be keenly watched by those interested in GM cane becoming part of the future of sugar production.

How Will GM Cane Be Regulated?

In most countries, GMOs are subject to stringent regulation, as people feel uneasy about altering the genome of an organism. New products are initially banned for import and production, and only approved if they meet a strict criteria. All countries, apart from the US and Canada, are yet to approve imports of sugar as a GM product.

The current regulations are based around the classification of a crop as a GMO, rather than a food as a GM product. The enforcement of these rules, therefore, relies on testing for the presence of genetically modified genes or their products. With this production process removing the introduced genes and the proteins they produce, it is impossible to impose these regulations on sugar. Sugar, therefore, falls into a grey area for classification.

The inability to trace the genetic origin of sugar poses a potential problem, however.

In Brazil, the production process does not segregate non-GMO cane from GMO cane, so it is impossible to separate the sugar at the first stage. Furthermore, the different sugar types are not transported or stored separately either. The inability to trace sugar from genetic origin, combined with the mixing of products at ports, means Brazilian sugar might be assumed to come from GMO cane. This could cause problems for the world’s largest exporter of sugar.

Brazil is keen to avoid this situation, so the Government and UNICA have been working to prove that sugar is a non-GMO product. In March 2018, the Brazilian government published in the Brazilian Federal that sugar originating from GMO cane is a “pure substance, chemically defined and, therefore, is not considered genetically modified”. Additionally, UNICA issued a new non-GMO certificate for sugar exports, attesting that Brazilian sugar does not have GMO traces, irrespective of the GM feedstock.

In a bid to retain the current exporting structure, UNICA has submitted a request to the Intercontinental Exchange (ICE) to confirm that GM cane sugar can be delivered to the raw sugar futures market. Interestingly, a non-GMO certificate is not one of the required documents by ICE for delivery, so, as it stands it, this sugar will be accepted onto the futures market.

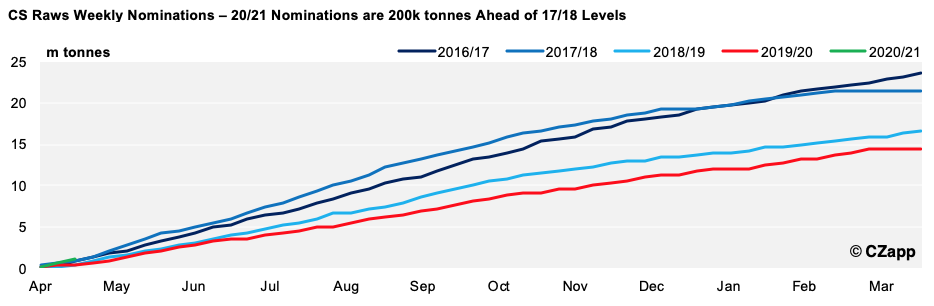

Offtake has been excellent so far and we have seen a record start of the season. At present, all destinations have accepted the new non-GMO certificate without further questioning, which has been potentially aided by the global anxieties around food security due to the coronavirus.

The apparent acceptance of the new classification could have major implications on the future of the sugar industry. If a precedent is set for the acceptance of sugar to be regulated as non-GM, this could incentivize global development and cultivation of GM Cane, pushing sugar production towards becoming akin to soybean or corn, in terms of its use of GMO varieties.

The arrival of GM cane sugar is likely to create pushback from anti-GMO groups. In particularly anti-GMO nations, import bans on any sugar originating from GM cane growing countries would likely be required to ensure its non-GMO origin. This could manifest in a two-tiered global market for sugar, with produce from non-GMO countries fetching a higher price because of the higher consumer demand. This has already occurred at a national level in the US, where GM beet is grown but GM cane is not. Certain industrial consumers currently only use cane sugar to ensure their product is GMO free, making it domestically more expensive than beet.

Consumer interest in non-GMO products means imports of this season’s Brazilian sugar will have implications on their purchasing behaviour. In most countries, GMO food is labelled, which often acts as a de-facto ban. Usefully for producers, if this sugar is accepted for import, it is unlikely that products containing it would be labelled as containing GMOs. However, it would equally mean the products cannot be labelled as GMO-free either, reducing demand for the sugar from firms that use GMO-free as a marketing tool.

There are also concerns surrounding in-country contamination of sugar from GM cane derived products. Most countries’ domestic markets utilise a small number of refineries, which mix sugar from a range of origins. If sugar is imported from Brazil, it would be impossible for a refinery to label a product as GMO-free. With this production bottleneck at refineries, the entire sugar supply could be compromised with GM Cane derived sugar, and it would not be possible to source GMO-free products. With some consumers exclusively choosing non-GMO products, this could have wider implications for sugar consumption.

What the Arrival of GM Cane Means for the Sugar Market

In 2019, almost 16m tonnes of raw sugar was exported from Brazil, accounting for 45% of global exports. This is expected to rise to over 60% in 2020, after Thailand and India had disappointing crops. Many countries are, therefore, dependent on Brazilian raws imports for food security and, in some cases, the support of their re-export refinery businesses.

With the Brazilian crop now underway, and exports off to a record start, it looks as though most countries have decided to accept the GM cane sugar. The approval of imports is just the start though. We will now see how this new product is handled by governments, industrial producers and consumers.

In the upcoming instalments of this series, I will discuss what this means for Brazil and the world market, before looking at the implications for the domestic industry and the major consumption regions. Finally, I will discuss what the future could hold for genetic modification in sugar.