Insight Focus

SAF is key to reducing aviation’s carbon footprint. A new report published by the NREL highlights the benefits of blending SAF upstream at terminals for efficiency. It also explores blending at terminals, refineries and new sites.

Although still in its infancy, the production and use of Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) will have an enormous impact on the airline industry and its effort to reduce the carbon footprint of commercial aviation. Additionally, SAF also promises to be a boon for ethanol and other biofuels industries.

Where and how biofuels are blended with jet fuel will be critical for the economic viability of the SAF-use concept.

A new report from the US National Renewable Energy Labatory (NREL) maintains that blending SAF at terminals upstream from airports, rather than at refineries, could be an essential practice for the industry. Before we explain, it may be helpful to provide some background on SAF.

SAF Logistics and Blending

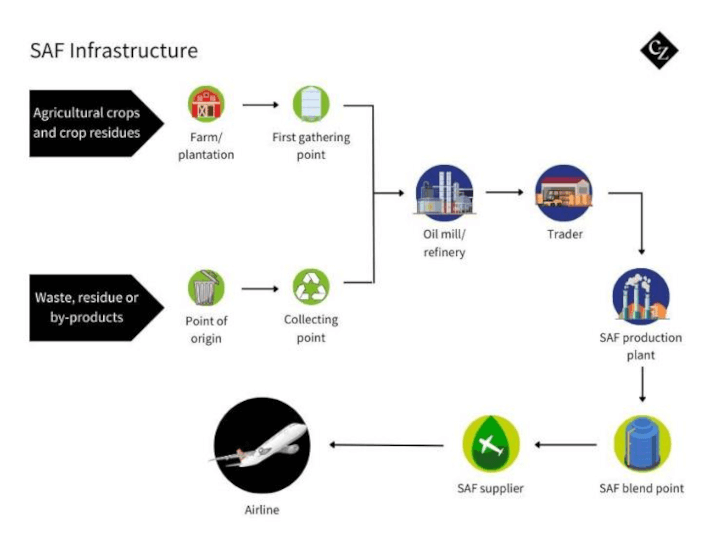

The new NREL report details the multiple modes of transit used to move imported and domestically produced Jet A and SAF to terminals, where the fuels are blended, certified and then delivered to airports by pipeline or truck.

Pipelines are the preferred method for moving any fuel due to lower costs and lower potential impacts from weather events. Domestically produced and imported jet fuel is commonly moved throughout the country by pipeline, passing through one or more terminals before delivery to an airport by pipeline or by truck.

The NREL report states that SAF from a stand-alone facility must be blended with Jet A prior to use in an airplane. Several possible locations for blending include existing terminals, airports, petroleum refineries and new/dedicated blending sites.

While all the locations evaluated are technically capable of blending fuel, there are practical considerations that make some locations less optimal. It is preferable to certify the SAF/Jet A blend as ASTM D1655, a standard that ensures the fuel meets the required quality and performance criteria for safe aviation use. This helps mitigate any potential fuel quality issues upstream of an airport. All locations will require capital investment to add infrastructure.

How the SAF market develops for the ethanol industry will certainly rely on economics to be the driving force behind the decision on where to blend. However, blending at terminals upstream of airports results in business as usual at airports, using the same pipeline, trucks, tank farms and hydraulic systems that are used to deliver the SAF/Jet A blend to aircraft.

A Background on SAF

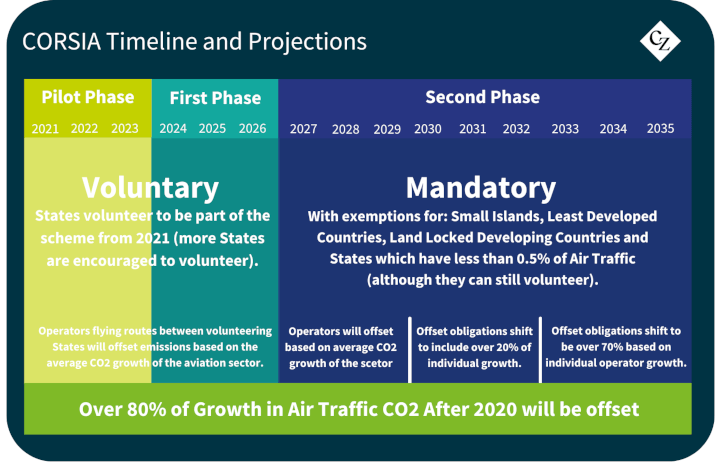

In 2016, the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), a specialised agency of the United Nations, adopted the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA) to cap net CO2 aviation emissions at 2020 levels through 2035.

Compliance began in 2019 for airlines exceeding 10,000 tonnes of annual emissions, with a requirement to record fuel usage for the purpose of calculating CO2 emissions.

Offsetting requirements, met through a variety of activities, began in 2021 for flights between voluntary countries, and full implementation will occur in 2027.

The International Air Transport Association (IATA), a trade association representing 330 airlines, adopted the Fly Net Zero initiative in 2021 to achieve net zero carbon by 2050.

Potential Locations for Blending

There are numerous SAF pilot plants and other commercial facilities under development worldwide. The NREL report notes that there are only four plants in the world supplying SAF to the US market. LanzaJet of Soperton, Georgia, is the only one that uses ethanol as feedstock, with the plant having a production capacity of 10 million gallons per year.

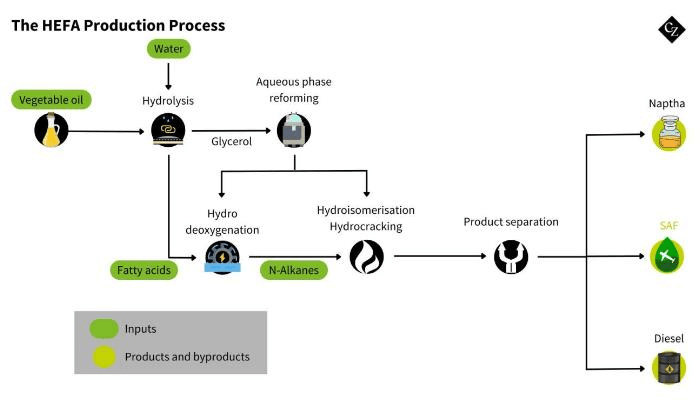

Other pilot plants, including Montana Renewables in Great Falls, Montana; Neste in Singapore; and World Energy in Paramount, California, all utilise waste fats, oils, greases and vegetable oils as feedstocks.

So, what are the options?

1. Terminals

Terminals are the optimal location for blending because they have existing tanks, associated equipment, blending software, trained staff, insurance and permits that cover these activities.

Nearly all terminals lease tanks and associated equipment to third parties for storage and blending activities. Terminals have long provided blending as a service for their on-highway transportation fuel customers. SAF storage and blending could occur in existing tanks, if available, but may require new tanks in infrastructure constrained areas.

2. Airports

Blending at airports is not recommended. This would be the first instance of certifying the SAF blend as ASTM D1655. An airport’s tank farm would require significant capital investment to add tanks for SAF storage, blending, additional off-spec tanks, associated equipment, software and additional staff.

There would be an increase in truck traffic delivering SAF, which would impact larger airports accustomed to receiving fuel by pipeline. Additional laboratory testing and paperwork are necessary for blended fuel. Different insurance would be necessary to cover blending activities.

EI 1533 is a guideline issued by the Energy Institute (EI) that states fuel blending should only occur upstream of airports. DefStan 91-091, a fuel quality standard used outside of the US, specifically prohibits the blending of aviation fuels at airport depots due to safety and quality concerns.

3. Refineries

Each refinery has a unique design, and its fuel storage is typically sized to match its production capacity, with little to no excess storage. Only a limited number of refineries have the capability to receive third-party fuel into their storage areas, and specialised off-loading equipment would be required for this process.

The refinery could receive the third-party SAF, blend with their Jet A, recertify, and transport fuel in a business-as-usual scenario by pipeline and truck to airports.

4. Greenfield/Brownfield sites

Establishing a new site or repurposing an existing industrial facility to store and blend SAF is feasible, but it would require significant capital investment. Obtaining the necessary permits for both the facility and any associated pipelines could take several years.

This option would likely only be considered in geographic areas with severe capacity constraints for existing infrastructure (terminals, pipelines, and rail).

SAF Mandates in the EU and Beyond

EU

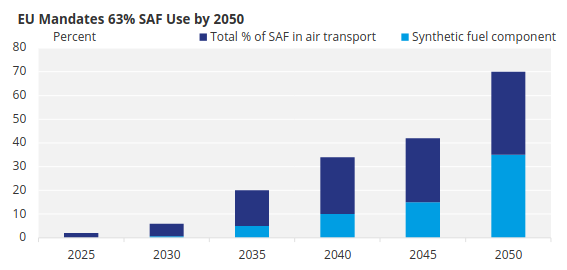

ReFuel EU is the European SAF mandate, passed in October 2023. The requirement escalates over time beginning with 2% in 2025, 6% by 2035, and 70% by 2050.

Source: EASA

The regulation allows the European aviation industry to use book-and-claim—a practice of decoupling the fuel credit from where it is used—until 2035, after which SAF must be physically supplied at European Union airports.

There are financial penalties for fuel suppliers who fail to meet the requirement. Sweden and France previously established SAF mandates of 1% in 2021and 2022, respectively.

UK and Norway

The UK SAF mandate requires 2% by 2025, 10% by 2030 and 22% in 2040. The mandate caps the common hydroprocessed esters and fatty acids (HEFA) production pathway and requires power-to-liquid fuels. There is a buyout price for fuel suppliers unable to secure supply.

In Norway, a SAF mandate of 0.5% has been in place since 2020.

The US

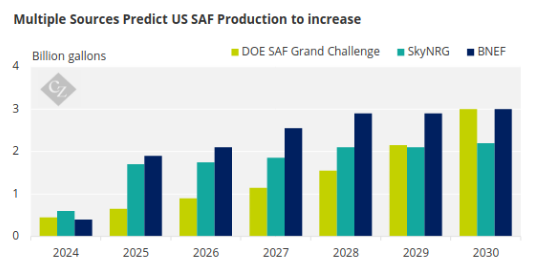

In the US, the Sustainable Aviation Fuel Grand Challenge is a joint effort from the Department of Energy, Department of Transportation, Department of Agriculture and other government agencies working to expand domestic SAF production, reduce costs and enhance sustainability. The productions target of neat SAF is 3 billion gallons by 2030 and 35 billion gallons by 2050.

The US is generally a net exporter of jet fuel. About 74% of 2023 exports were to other North American countries. Over the past five years, 50% or more of imports came from South Korea.