In the final months of 2019, there was a flurry of activity in the shipping industry as shipowners rushed to ensure compliance with IMO 2020 regulations, which required them to emit less sulphur during voyages. Now, the industry is in the final countdown before IMO 2023 regulations come into force, and these are much more complex. Regulations are sure to become even stricter as emissions goals are revised. The industry is set to change its goal of reducing emissions by 50% from 2008 levels by 2050 to reducing 100% of 2008 emissions by 2050.

What is EEXI?

EEXI stands for Energy Efficiency Existing Ship Index. The regulation comes into force on January 1 and applies to most ships with capacity of over 400 gross tonnes.

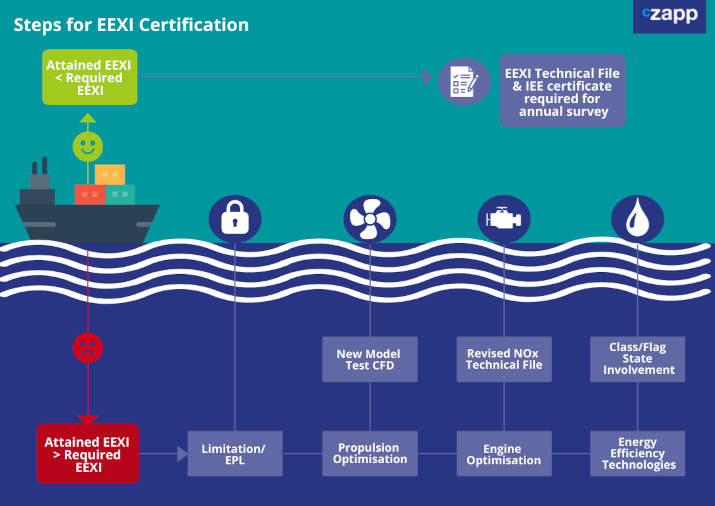

The good news for shipowners is that EEXI is measured once in a ship’s lifetime. The EEXI calculation is also theoretical and does not measure actual emissions. It takes into account the ship’s characteristics and design and how these factors impact efficiency.

Shipowners must present their calculations to the vessel’s classification society on its first survey that falls after January 1, 2023, whether it is an annual, intermediate or renewal survey. The Attained EEXI assigned to the vessel will be compared to a Required EEXI, which is determined based on the vessel’s type and size.

What is CII?

CII, or Carbon Intensity Index, applies to vessels over 5,000 gross tonnes and also comes into force on January 1, 2023. As the name suggests, this measure focuses on the intensity of a vessel’s pollution based on its capacity and distance travelled.

There is an extremely complex calculation that must be made that takes into account a range of factors, including the ship’s power, speed and fuel consumption. The final figure should give an idea of the vessel’s CO2 emissions per tonne of cargo over a nautical mile.

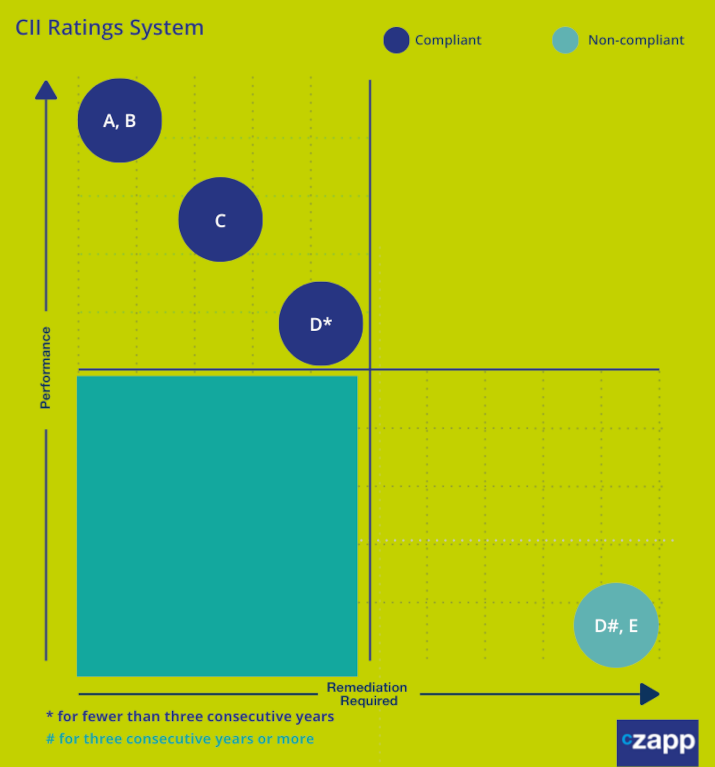

Unlike EEXI, this rating system is ongoing and vessel owners should compare the Actual Attained Annual Operational CII against the Required Annual Operational CII every year.

The ratings range from A (least emissions intensive) to E (most emissions intensive) but each threshold will change to become stricter towards 2030. This encourages continuous improvements on efficiency among vessels and voyages.

As part of the CII, all vessels will need to prepare a Ship Energy Efficiency Management Plan (SEEMP) and keep it on board the vessel. This document should contain the methodology used to calculate the ship’s Attained Annual Operational CII, as well as a plan of how it plans to achieve the Required Annual Operational CII for the next three years.

Who Bears Responsibility for Compliance?

Compliance ultimately lies with the shipowners. However, when it comes to time-chartered vessels, charterers are also likely to be dragged into the fray.

Owners of time-chartered vessels must comply with the charterer’s employment orders, but these could impact the CII rating of the vessel. Owners may decide to slow steam, modify cargo capacity or deviate routes to comply with the CII, but this could also mean they breach their charter and could be liable for damages.

This is especially true if these decision result in delays to the voyage, which breaches their obligation to proceed with utmost despatch.

Clauses will need be written into contracts that take into account the requirements of both parties, although there are several question marks over how this would work in practice. BIMCO has said it will develop a clause, initially for long-term charter parties, but plans to publish this clause in November, less than two months before the requirements begin.

How Will It Be Enforced?

Non-compliant ships can continue sailing during 2023 if remediation efforts are being carried out, but after December 31, they risk being detained or fined.

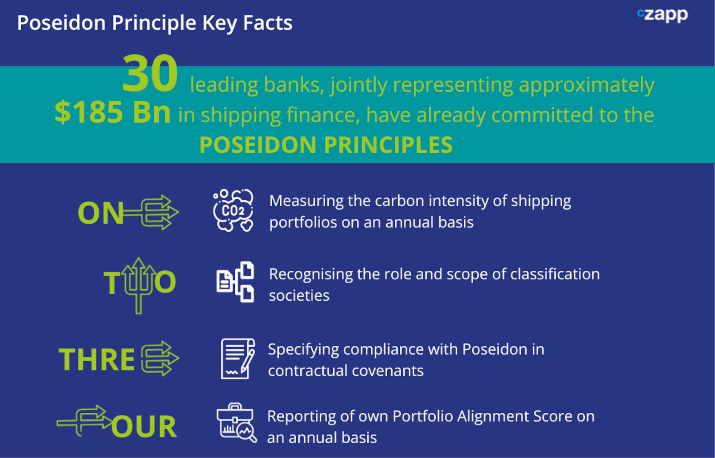

Just like other IMO regulations, the industry will be the ultimate arbiter. Non-compliant ships are unlikely to remain competitive in the market as charterers and investors seek to meet ESG principles.

More and more banks and non-banking investors are now pulling out of certain trades due to ESG concerns amid pressure from stakeholders. It is likely therefore that charterers will impose contractual obligations and that investors will require compliance from shipowners as a condition of funding.

What Are the Issues?

EEXI is reasonably straightforward, given that it requires a one-time certification for each vessel. However, there are certain implications that come with CII compliance.

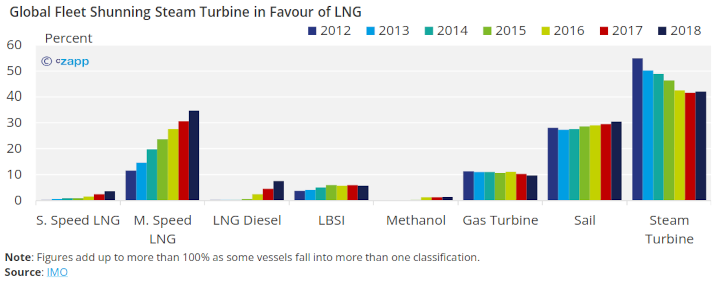

Importantly, there is no clear answer to how a global fleet that relies on fossil fuel will be able to change that. There are just not enough alternatives for the switch to happen, although uptake is picking up.

From 2012 to 2018, the penetration of LNG-powered ships in the global fleet rose significantly. The sulphur content in LNG is minimal but the cost of conversion of vessels can run into tens of millions of dollars. Natural gas prices are also on the rise.

Conversion is required to meet targets, but this may require government subsidies or incentives to promote cleaner marine fuels.

Another potential issue arises with the CII mechanism. These requirements could mean that higher-emitting ships will be allocated to longer voyages, meaning their carbon intensity drops. Lower-emitting ships would likely be assigned to shorter voyages. In the short term, this is likely to increase CO2 emissions rather than lower them.

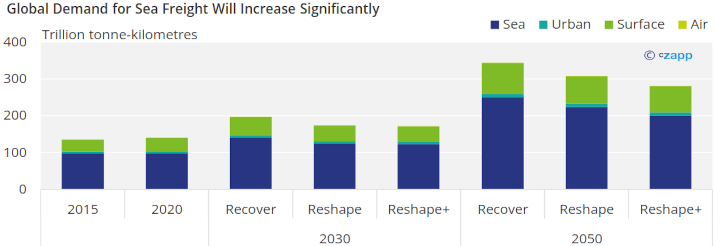

Another concern is that, as time goes on, the global vessel fleet will grow. Reducing emissions by 70% based on a 2008 baseline will be complicated by demand growth. By 2050, global sea freight demand could increase by as much as 155% compared to 2020.

Note: Recover, Reshape and Reshape+ refer to the three scenarios modelled by OECD’s ITF Transport Outlook

Source: OECD

Read more about how decarbonisation is challenging the shipping market here.