- The UK may implement a new tax on sugar and salt.

- It’s come under fire, however, as it could disproportionately impact lower-income households.

- There is growth in sugar free products, but choice is key.

New Sugar Taxes for the UK?

Two weeks ago, the UK government received the results of the National Food Strategy report, which was commissioned as a roadmap to improve national health outcomes.

The first recommendation made by the independent review was the introduction of a tax on salt and sugar, the revenue from which would be used to supply fresh fruit and vegetables to low-income families.

The committee recommends a 6 GBP/kg tax on salt and a 3 GBP/kg tax on sugar sold for use in processed food or in restaurants and catering businesses. This is roughly equivalent to 8,355 USD/mt and 4,177 USD/mt, respectively. The tax will supposedly generate between £2.9 billion and £3.4 billion per year for the Treasury.

What’s the Link Between Sugar and Health?

According to Diabetes UK, weight gain increases the risk of contracting diabetes. As added sugar contains a lot of so-called “empty calories,” it contains a lot of calories but doesn’t necessarily fill us up. It’s therefore been highlighted as a cause of weight gain, and indirectly a causal factor of diabetes. Essentially, sugar is often linked with weight gain because it’s very easy to overindulge.

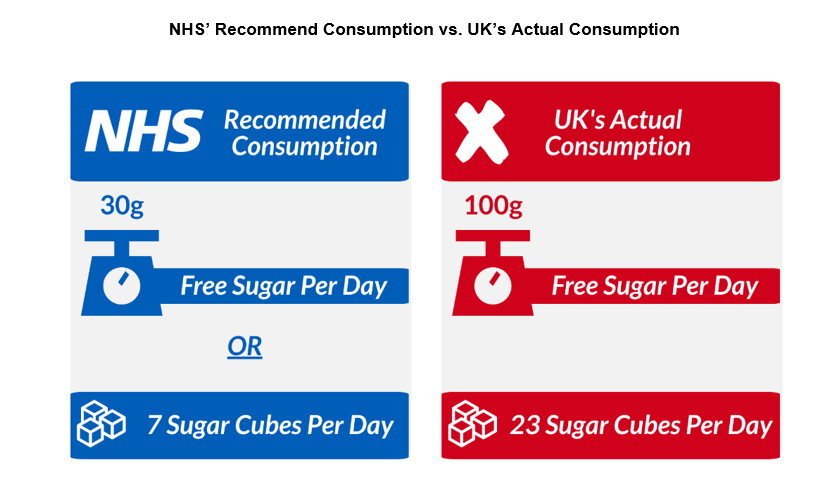

The UK’s National Health Service (NHS) recommends consumption of 30g of free sugars per day for an adult, which is roughly equivalent to seven sugar cubes. Some estimates show that UK weekly consumption of sugar could be as high as 700g per person, or more than three times the recommended amount. Czarnikow data puts average per day consumption at about 74g per person per day as of 2021.

However, it’s also worth noting that the Government’s sugar consumption guidance has been decreasing over the last few decades. In 2015, it halved recommended daily intake levels from 60g after new recommendations were made by the Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN).

Currently, the NHS says that around 2 million GP-registered patients have non-diabetic hyperglycaemia, which puts them at high risk for developing diabetes. Diagnosed and undiagnosed cases of Type 2 diabetes is already at 4.7 million and this could reach 5.3 million by 2030.

The UK diet requires change, according to the National Food Strategy Report, but there are plenty of indicators that show sugar consumption is not the only issue. That is why, in addition to a targeted 25% reduction in high fat, sugar and salt content, the committee recommends that the public also increases fruit and vegetable intake by 30%, increases fibre intake by 50 and reduces meat intake by 30%.

Also, the COVID-19 pandemic has notably exacerbated the health situation in the UK, with countrywide lockdowns and quarantine periods imposed for most of the year. Studies have shown a drop in physical activity and an increase in sedentary behaviours since March 2020.

According to research from Public Health England, more than 40% of adults gained weight during lockdown at an average of 4.1kg. This is even more concerning for the already-burdened NHS as studies have found that obesity is a factor in severe COVID-19 cases. In the study, there were worse outcomes for those who contracted COVID-19 and also had a BMI of above 35.

What Would the New Tax Mean for Our Favourite Products?

In the face of higher costs generated by the tax, food manufacturers have two real choices: pass the additional costs on to the consumer or reformulate recipes to ensure they contain less sugar.

If the costs are passed on to the consumer, some of the UK’s favourite sweets and chocolate bars could increase in price.

Kit Kat, for example, sells around 156 million bars per year. At 10.2g of sugar in a standard 20.7g bar, manufacturers would be looking at an additional £4.78 million in costs per year with the new tax.

Mars Bars, 81 million of which are sold annually in the UK, have 23.6g of sugar in a standard 39.4g bar and manufacturer Mars would have to either bear additional costs of £5.73 million per year or hike prices.

What Are the Main Criticisms of the Tax?

The first criticism is that it will disproportionately impact lower-income households.

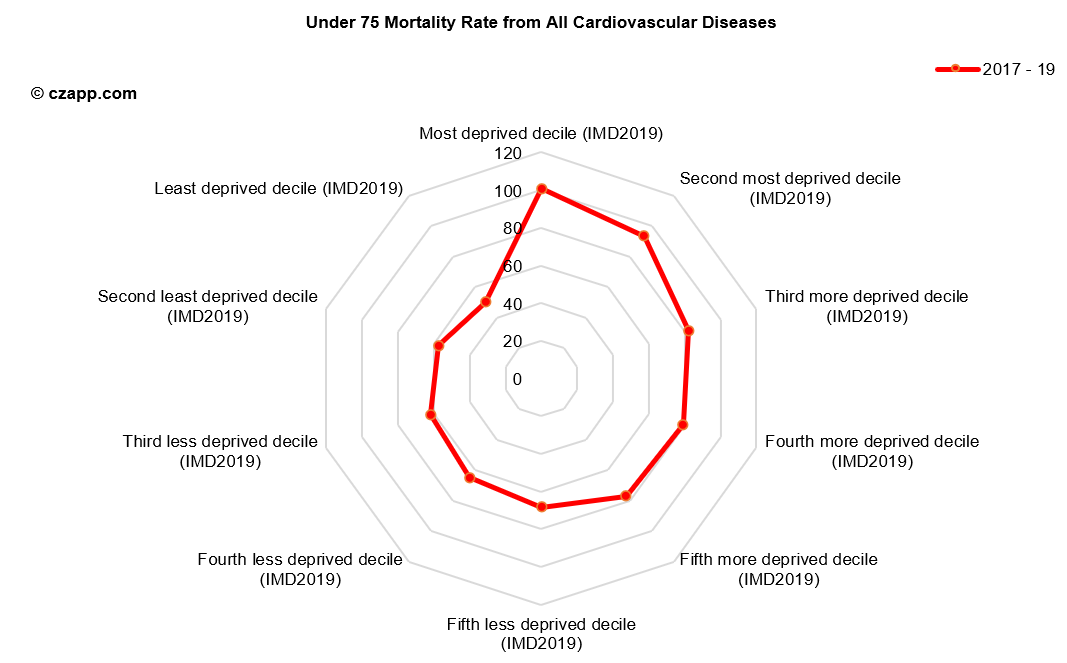

According to Public Health England figures, there’s a correlation between the prevalence of diabetes and the 2019 deprivation score, suggesting a link between income and health outcomes. Data also shows that the prevalence of under 75 mortalities from cardiovascular diseases is heightened among the most deprived decile of the population.

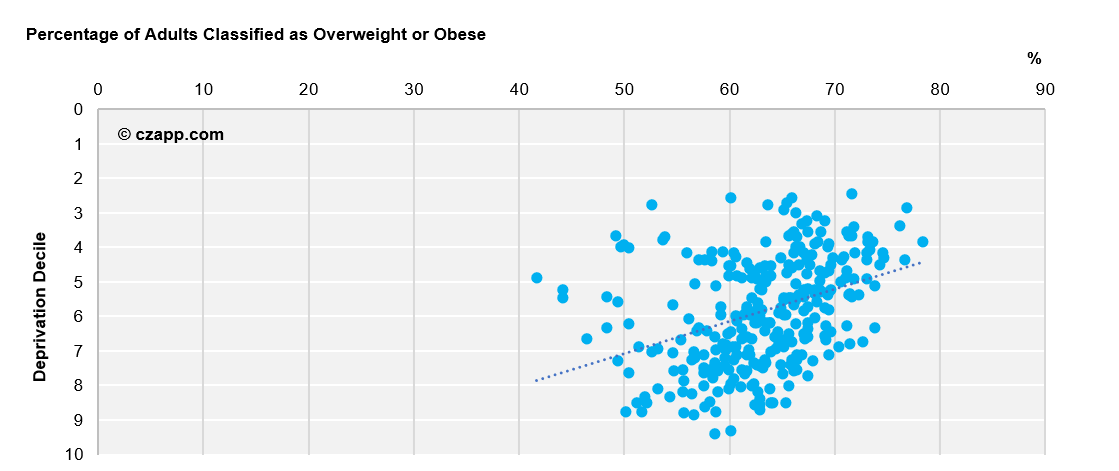

Likewise, there’s a positive correlation among authorities in England’s position on the deprivation index and the percentage of adults classified as overweight or obese. Less deprived areas typically register lower rates of obesity.

To address the UK’s poor health outcomes, the issue of affordability must also be addressed, which many say is inconsistent with a tax.

A Food Foundation report found that the poorest fifth of UK households would need to spend 40% of their disposable income to comply with Eatwell Guide guidelines. Industry leaders have also already warned that, if the proposed salt and sugar tax is passed, annual grocery bills will rise by £160, which is beyond the reach of many low-income families.

Another argument is that the sugar industry shoulders a lot of the blame for the UK’s health problems. Notably, no taxes were proposed for meat despite the recommendation that consumption should be cut.

The report’s authors wrote that targeting meat consumption is “not politically feasible” and that the implementation of such a measure would be too complex.

The Turning the Tables report released by think tank, Demos, in August said in its recommendations that the Government should fund the development of lab-grown meat alternatives. It also suggested that new packaging rules should come into force for HFSS foods rather than a tax.

Why a Sugar Tax?

The UK has a precedent of taxing sugar consumption.

In 2018, the Government introduced a tax on sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs), mandating a 24p per litre levy for any drinks containing more than 8g of sugar and an 18p surcharge for drinks containing between 5g and 8g of sugar. Pure fruit juice and drinks with high milk content were exempted.

Rather than paying those taxes or passing the additional costs on to consumers, most soft drink manufacturers instead reformulated their recipes to drastically cut their sugar content. A.G. Barr, for example, slashed the added sugar in its Irn Bru to 4.7g from 10.3g, swerving under the 5g threshold.

As is human nature, nobody wants to be told they cannot have something. A “Hands Off Our Irn Bru” campaign kicked off and was signed by about 50,000 people to protest the move. In response, the company acquiesced and released a limited edition 1901 version with even more sugar than the original recipe.

But profits remained largely intact. A.G. Barr recorded a 5.6% increase in its full year 2019 revenue to £279 million and in the same year the reformulated Irn Bru regular increased its volume share of the total UK carbonates market by 4.2%.

That same year, the firm reported that sugar free versions Irn Bru Xtra and Irn Bru Sugar Free now account for 40% of the total Irn Bru brand sales on a volume and value basis and these versions are growing in popularity. The Irn Bru saga suggests that we do like sugar free and low sugar options, but we balk at the prospect of the choice being taken away from us.

The National Food Strategy aims to use the soft drinks success and duplicate it across all products with high sugar and salt content. The plan, headed by restaurant entrepreneur Henry Dimbleby, expressly states that the aim is to encourage manufacturers to reformulate recipes rather than shoulder taxes. In the report, the committee says the measure could be a way to incentivise the industry, which is reluctant to cut sugar content independently out of fear of being undercut by competition.

The report estimates that the tax would reduce average sugar intake in the UK by between 4g and 10g per person per day, contributing to a 15 calorie to 38 calorie per day reduction, which it says would be enough to stop weight gain across the country.

How Easy Will Reformulation Be?

Dimbleby has already admitted this will be easier for some products than others.

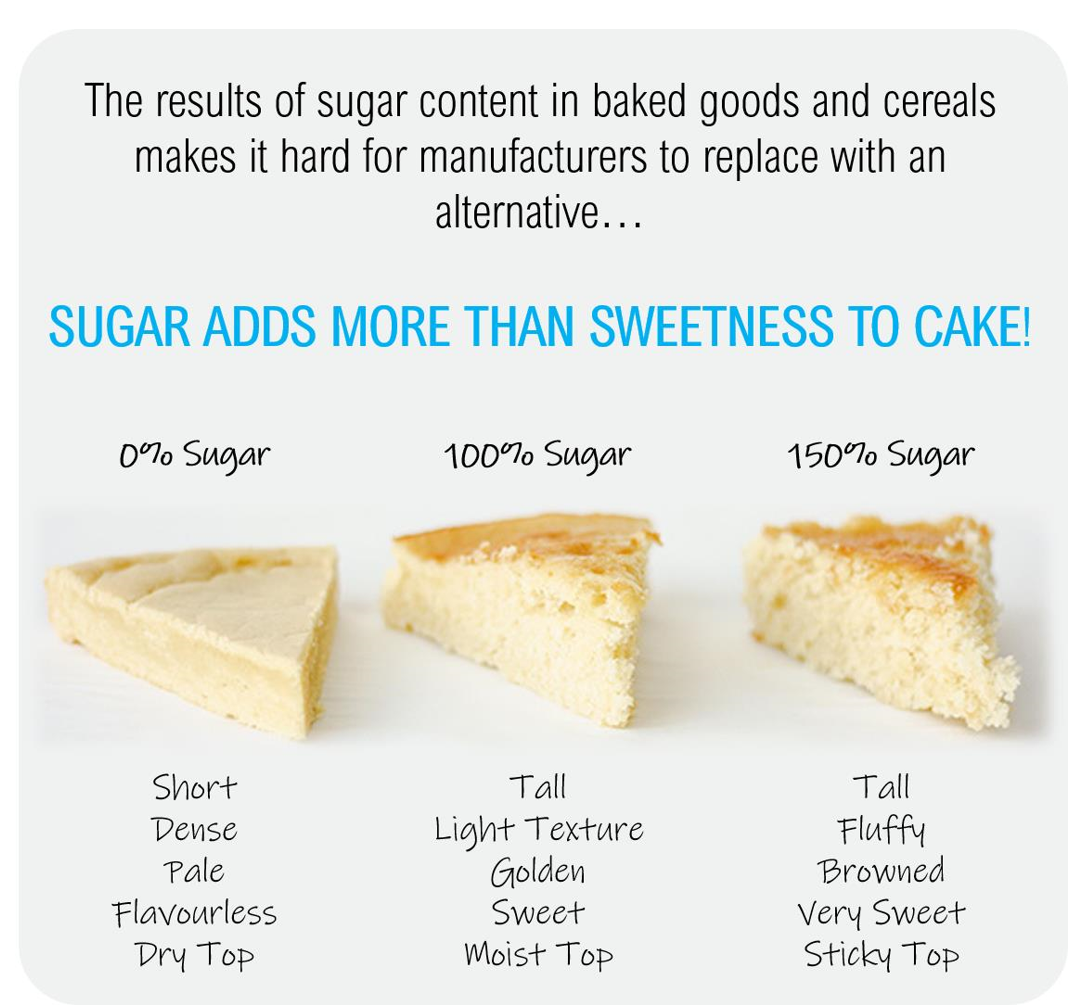

In the case of soft drinks, sugar has little other purpose than to provide a sweetening effect. However, for certain confectionaries, such as cakes and biscuits, the process could prove to be slightly more complex.

As we all very much know from the lockdown baking phase, even one slightly miscalculated measurement can mean the difference between a perfectly moist banana bread or a doorstopper with the consistency of sand. In baking, sugar not only provides sweetness but is also hygroscopic; it attracts and holds onto water molecules, preventing goods from quickly drying out.

In other cases, such as with cereals, it can add texture, colour and flavour, and it may be difficult for manufacturers to exactly replicate its properties with artificial sweeteners.

Will the Government Adopt the Tax?

This remains unclear.

The stress levied on the NHS by COVID-19 may warrant the need to cut costs or generate extra income, which is where the proceeds from the tax could prove beneficial.

According to the authors of the plan, its adoption would go some way to halting the prevalence of diabetes, which is estimated to cost the NHS £15 billion each year. Poor diet contributes to around 64,000 deaths annually in England alone, they add.

An alternative to the tax that could help bridge the NHS deficit is a hike in National Insurance, a move that’s proving controversial among cabinet ministers and MPs.

But despite having commissioned the report, the Conservative government is traditionally less inclined to take action that could be seen as promoting a “nanny state”. According to reports, instead of the stick, the Government could instead use the carrot with a reward program for healthy eating that would use an app to track supermarket spending and generate rewards for healthier choices. Extra points would be gained for carrying out exercise.

It’s also worth noting that Prime Minister Boris Johnson ruled out adopting measures that would increase food bills.

What Will the Implications Be Beyond the UK?

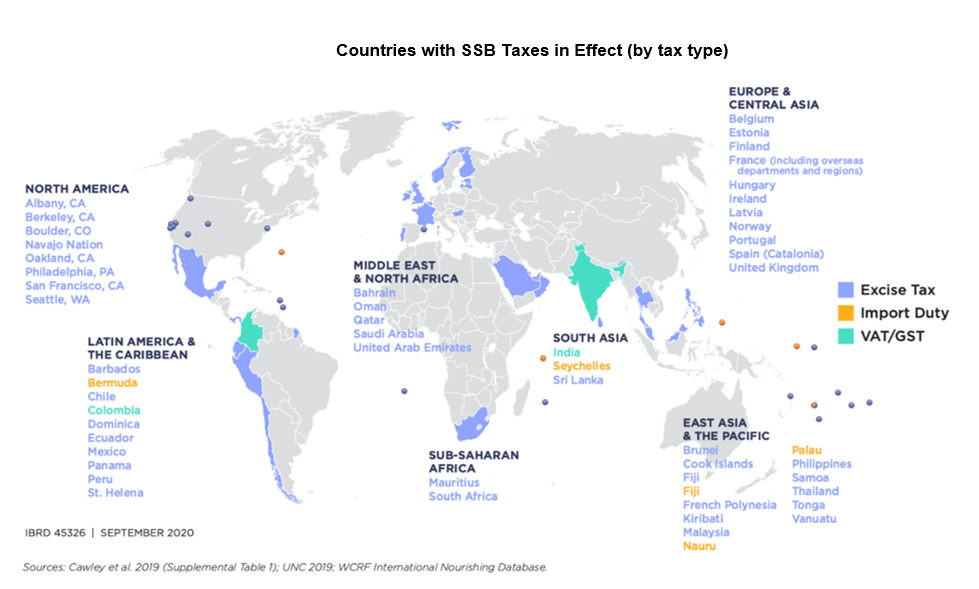

The UK is not the only country to have imposed a tax on sugary drinks.

The first health related SSB taxes were imposed by French Polynesia, Nauru, and Samoa in the early 2000s, along with European nations Denmark, Finland, Hungary and France from 2009 to 2012.

As of January 2020, more than 50 countries globally have imposed taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages and some regions, such as Catalonia in Spain and Berkeley in California (USA) have enacted their own tariffs.

But until now, beverages have been the main focus of taxes, given the relative ease of reducing their sugar content compared with other products. If the tax on all sugars and salts is adopted in the UK and has an impact on health outcomes, other countries may look to replicate the measure, and this could have an impact on confectionary companies around the world.

So, Do Taxes Really Curb Sugar Consumption?

The short answer is that we don’t really know yet. In the UK, the tax has been in place for about three years, so the socioeconomic data on health outcomes so far is scarce.

A study carried out in Thailand after a similar implementation period found that overall SSB consumption did decline. However, the decrease was found to influence the elderly, lower-income, and unemployed populations, with the researchers noting that the tax seemed not to work among the higher-educated and those with more stable incomes. The study also concluded that, despite a demonstrated decrease in sugar consumption, the impact on obesity and diet-related non-communicable diseases is “hardly discernible”.

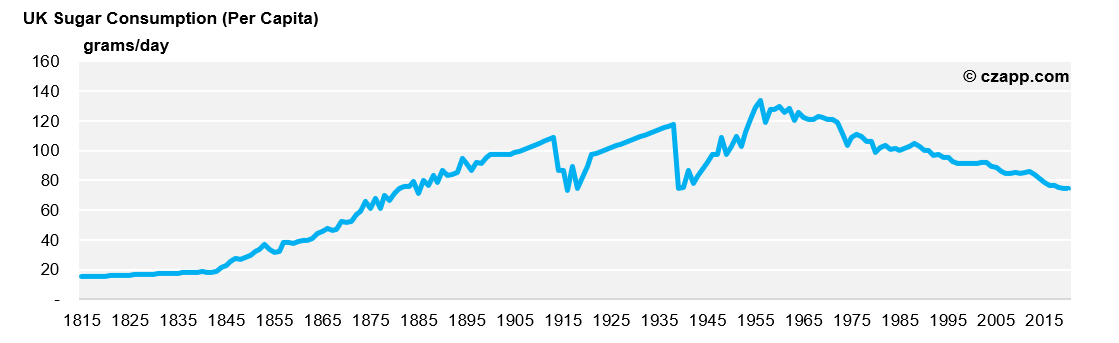

What’s more, sugar consumption in the UK has actually been declining on a per capita basis long before the SSB taxes were introduced. After a peak of 134g per person per day in 1957, there’s been a steady decline to the present day. Current per capita sugar consumption is about 74g per person per day on average in 2021 – still more than double the current recommendations but a marked improvement on past years.

What Will This Mean for Sugar Consumption Levels?

One thing that seems clear is some companies are actively searching for ways to reduce sugar content in their products. The sugar-alternative market is worth an estimated $16 billion to $20 billion and some companies are voluntarily reducing sugar content, even when no taxes are in place.

In Brazil, between 2017 and 2018, the Government reduced sugar taxes, but the industry continued to develop drinks with lower sugar content. And Premier Foods, the owner of the Mr. Kipling brand, said sales increased by 7.5% in its most recently reported quarterly earnings after it introduced low sugar options.

The impacts of the UK’s SSB tax have been modelled and show the best outcomes come from SSB reformulation and an increase in market share of low-sugar drinks, rather than an increase in prices. The increase in prices is estimated to result in a 0.5% drop in obesity, compared with a 0.9% drop for reformulation and a 0.6% drop for increased presence of low-sugar drinks. So yes, taxes seem to work, but maybe not as effectively or as equitably as other options.

Also, it seems the preference for low-sugar options is growing stronger but that doesn’t mean we don’t want a choice…

Other Opinions You Might Be Interested In…

- Brexit: What’s Changed for Sugar?

- Sugar Taxes: Going Up Because of COVID?

- Sugar Consumption and Reformulation

Explainers You Might Be Interested In…