Insight Focus

- Decarbonising each industry comes at a different cost.

- Many EU industries are covered by the Emissions Trading Scheme.

- The ETS creates a single price for carbon emissions.

The EU Emissions Trading System covers a wide range of industries and processes, each with their own cost of carbon abatement.

For many of these industries electricity plays an important role, and while the advent of grid-scale solar and wind power has enabled many plants to switch away from fossil-fuel fired on-site generation, there are still many processes that have yet to find low- or zero-carbon alternatives.

Decarbonising these individual processes will come at different costs. The cost for a cement plant to reduce greenhouse gases from clinker production is clearly not the same as for an oil refinery to reduce CO2 from distillation towers.

Yet these and others are all covered by an EU ETS that creates a single price for carbon emissions allowances. The market includes more than 9,000 individual installations, ranging from the giant Belchatow coal-fired power station in Poland to BMW’s Steyr, Germany assembly plant.

The dominant sector in terms of overall GHG emissions is the power sector, and it is the economics of cutting CO2 from power generation that have come to set the prevailing market price of EU emission allowances (EUAs).

According to data from the European Commission, emissions from electricity generation totalled more than half of the total 1.3 billion tonnes of emissions covered under the EU Emissions Trading System in 2021.

Because utilities receive no allowances free of charge – power plants need to buy every EU allowance at auction or in the secondary market – the price of carbon is more significant for power generators than for other sectors.

The goal of the EU ETS is to impose a cost of emitting, and thereby to bring the external environmental cost inside a company’s financial accounting.

For power plants, this can be expressed as the difference between the marginal cost of electricity with – and without – the cost of carbon included.

Burning coal for power emits roughly 1 tonne of CO2 per megawatt-hour of power generated; natural gas emits roughly 0.5 tonnes per MWh.

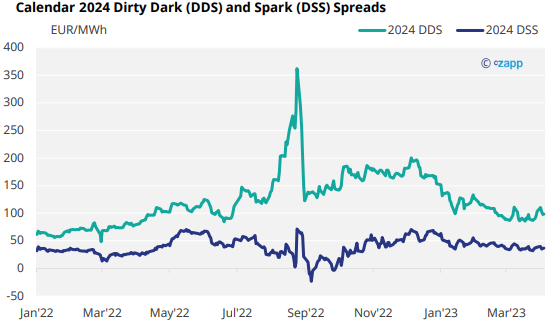

The so-called “dirty dark spread” (DDS) and “dirty spark spread” (DSS) represent the respective operating profits for a coal-fired and gas-fired power plant. Input costs are simply the coal or gas needed to run the plant, and the chart below shows the evolution of the DDS over time.

The chart above shows that based purely on the cost of fuels, using coal to generate power is considerably cheaper than natural gas.

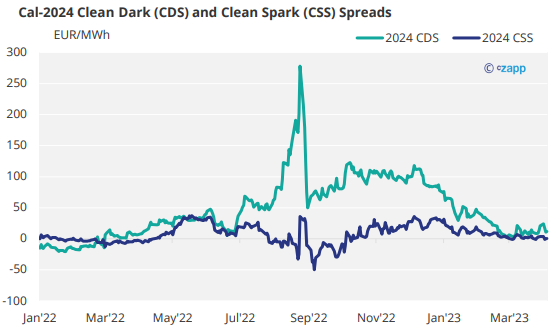

The addition of the respective cost of the carbon permits required to generate one megawatt-hour are applied to these spreads to generate “clean dark” and “clean spark” spreads, as shown below:

The chart above shows that in the early part of 2022, using natural gas to generate power in 2024 was more profitable than coal, though that advantage was lost in the run-up to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, as we will discuss below.

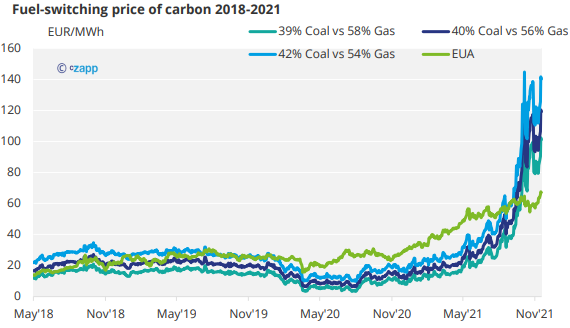

The clean dark and clean spark spreads can also be used to generate a theoretical “fuel switching” price of carbon, depending on the thermal efficiencies of the plants involved.

From these calculations, we can infer a price of carbon allowances that – all other things being equal – generates the need to switch from coal to gas.

And it is this “fuel switching” cost of carbon that historically influenced the price of EUAs in the years leading up to 2022, as the chart below shows.

The EUA price (in green) steadily rose until it was high enough to force even the most efficient coal-fired plant to be switched off in favour of natural gas.

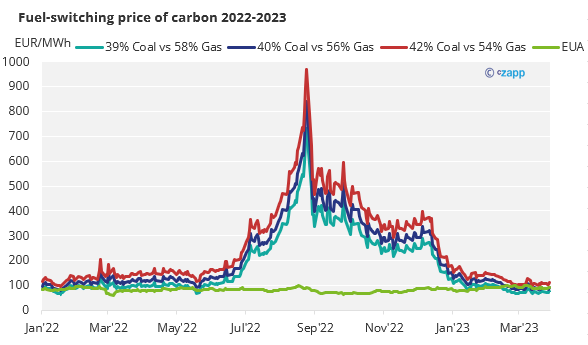

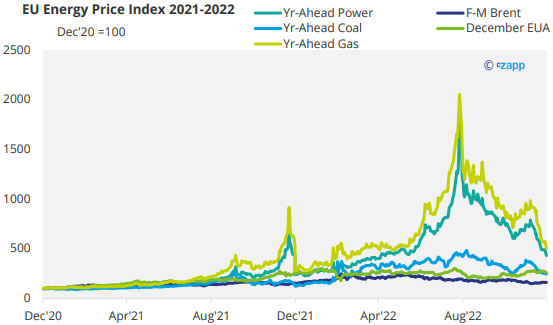

This fuel switching price was rendered moot during the tumult in energy markets in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine:

Gas prices rose to such levels that the fuel could not be economically used to generate power compared to coal, and so coal enjoyed a renaissance across Europe’s power sector.

This was chiefly because the EUAs did not rise by anything like the same extent as energy prices. The need to conserve gas supplies meant that coal was favoured both practically and financially.

EUA prices did rise, supported by increased demand from utilities that were using more coal, but while gas prices rocketed nearly eight-fold at the end of 2021, and electricity prices jumped six times over, EUA prices merely doubled.

The market is currently seeing gas prices decline from last year’s peak, though to be sure they are still multiples of the level they were before the invasion. However, coal and power prices have also risen, and at the present time gas is only marginally “out of the money”.

This means that the carbon price is approaching the levels where it needs to be in order to force switching away from coal to gas for electricity generation. However, energy prices are still several multiples higher than where they were before the energy crisis began.

The picture is clouded by political considerations. EU member states have agreed that gas storages should be 90% full by November, and this will dictate where gas production and imports are sent.

This could mean that natural gas prices may rise high enough to encourage stockpiling rather than consumption for long enough to ensure next winter’s supply.

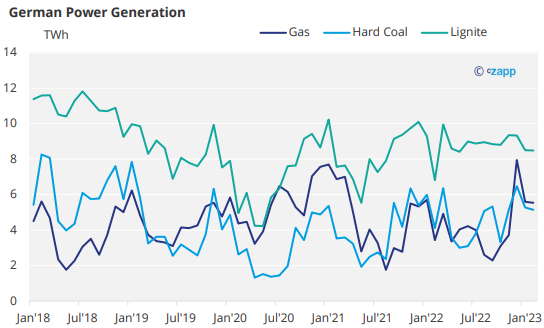

To be sure, natural gas is still being used to generate power at peak times, and when renewable sources are running at low rates. The economics of the peak power market are significantly different than for baseload generation, but gas still accounts for a significant proportion of power generation in Germany, for example:

Nevertheless, as the share of coal in Europe’s power generation declines over time, gas-fired power will then need to compete with zero-carbon alternatives like wind and solar, while battery technology is expected to improve as well, reducing the need for thermal (fossil) generation even further.

***

While fuel-switching has long been the main price-setting mechanism for carbon prices, it’s also relevant to consider the role of investors and speculators who have become particularly active in the market in the last three or four years.

The price of emissions is generally expected to rise as the cap on emissions declines each year. After formally agreeing to cut emissions by 55% from 1990 levels by 2030, the EU is about to begin consultations on setting a target for the bloc for 2040, on the way to its 2050 goal of achieving net zero emissions

Investors have determined that Europe’s policy framework is solid and ambitious, particularly after the European Commission implemented measures to slash the historic surplus of allowances in 2017.

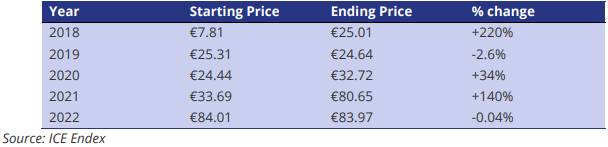

As a result a surge in speculative activity in 2018 helped triple the price of carbon permits, and prices added a further 150% in 2021 as more investors joined in. Around 400 investment funds presently hold positions in the EUA futures market.

Investors may take a long-term view on the price of EUAs, focusing chiefly on the policy environment, but others are more concerned with exploiting day-to-day and even intraday price moves, and hold no views on the longer-term price direction.

While no data exists to confirm, anecdotal sources also point to algorithmic trading playing a growing role in the market’s increased price volatility.