Opinion Focus

- Rice is a staple for 50% of the global population, mainly in poorer countries.

- Historically, rising rice prices have coincided with social unrest.

- Attention should be paid to curb rising rice prices and guarantee global supply.

While the price of almost every commodity has skyrocketed at some point in the past few years, rice has been one of the only foodstuffs that remains affordable. Rice is the staple food of half of the global population, primarily across Asia. It serves as a tool of food security for the lower-income populations since it is cheap, accessible and filling. This means a potential increase in rice prices could signal a worse crisis than rising prices of other grains.

Rice Represents Food Safety Net

Prices of wheat have risen exponentially since the war in Ukraine began, fuelling food security concerns. But there has been little talk about rice as a means of preventing world hunger.

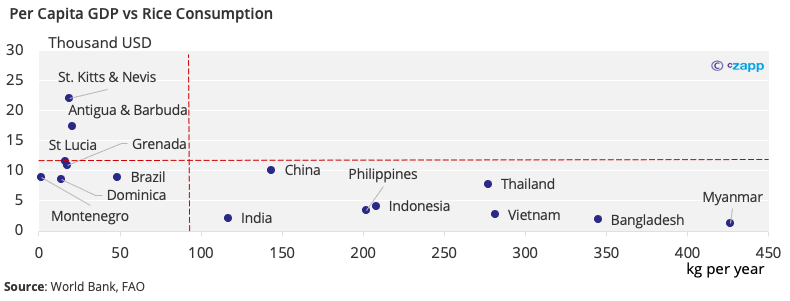

While some low-income countries do not have a high rice intake in their diets, rice tends to make up very little of total calorie intake in high income countries.

Meanwhile, on a per-capita basis, most high rice consuming countries fit into the low GDP bracket.

As Rice Prices Rise, So Does Unrest

Ukraine is a minor rice exporter, with just 10,000 tonnes exported in 2021, compared with almost 19.4 million tonnes of wheat. For this reason, the price of rice has not been affected by the conflict.

But rice prices are vulnerable to other factors. Rising commodity prices, although having cooled off recently, could push rice prices up alongside other items in the commodity basket. Looming inflation is likely to exacerbate the situation.

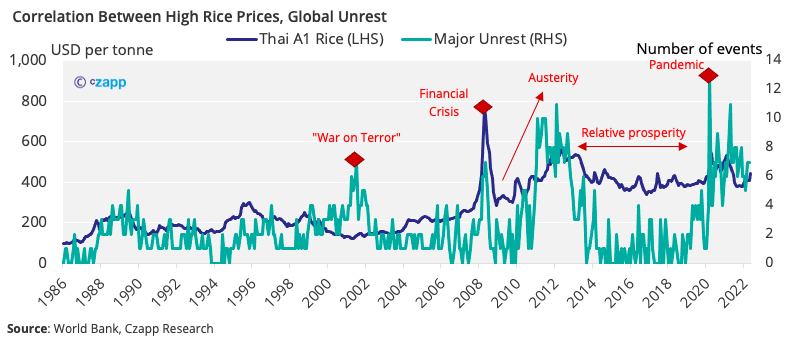

This in turn is likely to lead to global unrest as has historically been the case. Czapp cross referenced the price evolution of Thai A1 rice against the prevalence of major conflict and unrest in the past 35 years.

Some periods of unrest did not correspond with significant rice price rises, as was the case of the Covid-19 pandemic. However, in every instance of rice price rises, there has been an increase in global unrest.

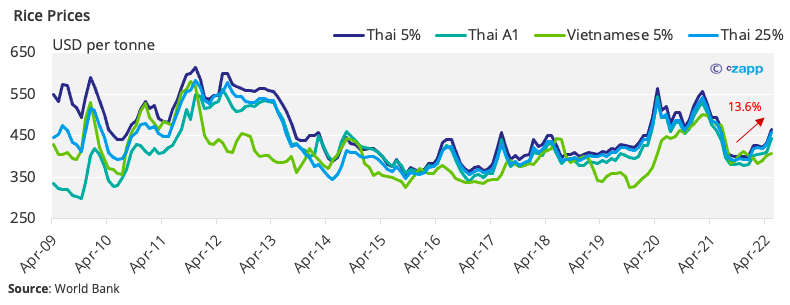

The price of rice has been rising alongside the wider commodity market since mid-2021. On average, prices have risen about 13.6% — a much lower rate than for some other commodities.

While prices haven’t risen much yet, risk remains. First of all, general food inflation is likely to cause rice prices to rise globally. In April, the IMF revised inflation projections upwards by 1.8 percentage points to 5.7% for developed economies. For developing economies, projections went up 2.8 percentage points to 8.7%.

Supply-Demand Imbalances Pose Risk

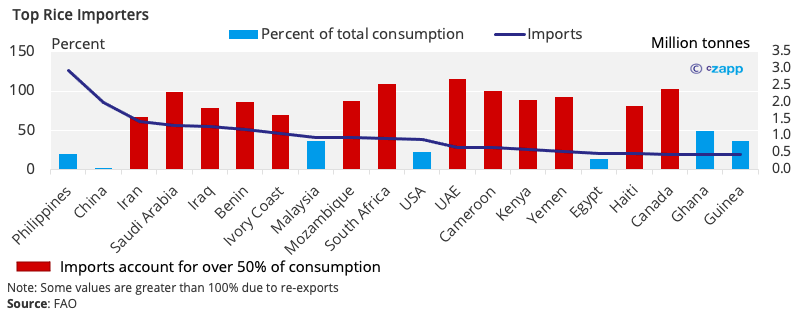

A second risk factor for rice prices is the threat of constrained supply. Imported rice accounts for over 50% of total consumption for 13 of the top 20 importers. These countries are mostly low or middle income, and some, such as Yemen, will also face additional pressure from rising wheat prices – another staple in the diet.

Prices Hang in the Balance

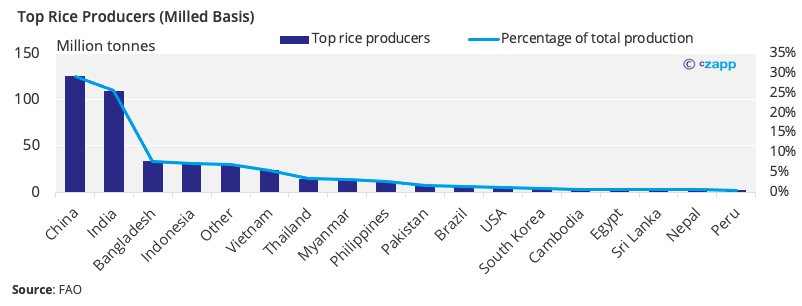

By far the world’s biggest rice producer is China, which accounts for almost 30% of global supply. India accounts for just over 25%. Rice production generally is concentrated in Southeast Asia, with small pockets of production in the Americas and the Middle East.

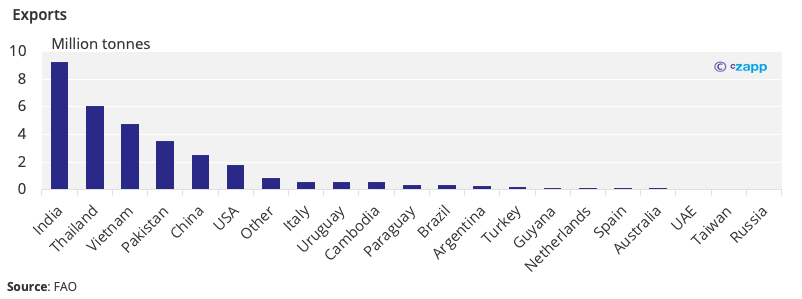

China and India are also major rice exporters, alongside Thailand, Vietnam and Pakistan. India accounts for almost a third of global rice exports. Thailand, Vietnam and Pakistan export 18%, 15% and 10%, respectively. China consumes most of its production domestically but still accounts for just under 8% of global exports.

Although India has not announced any plans to ban rice exports, its vast production and export capacity means any change in policy or move toward protectionism could quickly drive prices up. Given the recent decision to ban wheat and cap sugar exports, there are fears that rice could be next as global grains stocks run down.

China’s rice harvest for this year has also been under the microscope. According to Fitch Ratings, China’s Covid lockdowns pose a risk to production. The ratings agency says that the scope of the lockdowns may continue to widen, which may disrupt transportation of inputs and farmer mobility. This in turn would jeopardise spring planted grains, one of which is rice.

There are also severe weather events in major rice producing regions. Guangxi and Guangdong are both experiencing heavy summer monsoon rains, while fellow rice producing region Jiangsu is facing severe drought.

If China’s rice harvest falls short of expectations due to these events, this could also impact regional trade amid the remaining three top producers. Pakistan already exports vast amounts of rice to China, but any shortfall in domestic production could cause Chinese importers to look to neighbouring Thailand and Vietnam to shore up supply.

Concluding Thoughts

- Rice prices have so far not risen at the same rate as other commodities.

- However, the role of rice as a food safety net cannot be underestimated.

- The commodity is a staple for about 50% of the population, mainly in poorer countries.

- A close eye should be kept on key indicators, including supply constraints and trade dynamics.

- A rise in the price of rice is likely to trigger widescale unrest in countries that depend on it.

Other Insights that may be of interest

What the Energy Crisis Means for Inflation & Commodities

Ukraine Crisis Adds Another Twist to Sudan’s Food Insecurity Spiral

Interactive Data Reports that may be of interest …

Consecana Panel

CS Brazil Weather Update