Insight Focus

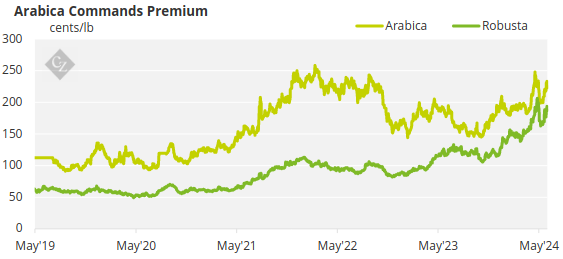

Coffee prices have soared since 2020, with the dominant arabica blend rising from 96¢/lb at the end of May 2020 to around 222¢/lb at the end of May 2023. What has caused this rally, and what’s next for coffee?

Arabica Versus Robusta

Arabicas are usually the dominant force in coffee, with robusta futures closely following the trend set by the arabica futures market. Arabicas play a leading role because they are considered to be of superior quality and are responsible for just under 60% of all coffee production. Volumes on the ICE arabica futures market in 2023 were four times the size of those on the ICE robusta market in terms of bags of coffee.

This year, however, has been different, with the bullish narrative in robustas providing support to prices across the whole coffee sector. The strength of robustas has spilled over into arabica futures as many funds are unable to take positions in the robusta futures market because of its lack of liquidity.

So, funds looking to take advantage of the supply/demand tightness in robustas, and by extension the whole coffee market, are forced to take long positions in the more liquid New York arabica futures market.

The Coffee Market Rallies

The unprecedented strength of robusta is seen in both the level and structure of the futures market, with the July contract hitting a 45-year high of USD 4,338/tonne in April and the premium of the nearby contract over the second month contract trading at over USD 200/tonne during the May delivery period.

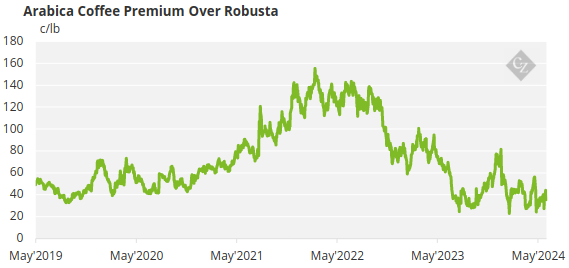

As a result, the arbitrage between the second month arabica and robusta contracts, which had traded at 70¢/lb in December, has fallen to 40¢/lb by the end of May.

The arbitrage did not move down in a straight line but has tended to move higher as funds enter the market in New York, pushing prices higher, and coming down in market dips.

The surge in robusta futures has been dramatic, but it doesn’t fully capture the drama of the price explosion in the physical robusta market. Vietnam Grade II coffees are the standard robustas for the large multinational roaster. These coffees were trading at negative FOB differentials in the first quarter of 2023, but this year differentials have soared to more than USD 1,000/tonne. It has since come down to around USD 800/tonne.

A standard Brazil Fine Cup arabica was trading at around an 85¢/lb premium to a Vietnamese Grade II robusta in the first quarter of 2023, but now Grade II’s are trading above some standard Brazil arabicas on a flat price basis. This change has devastated the budgets of roasters working with a fixed robusta component in their blends.

Why Robusta?

The tightness in robustas has come about because production has been unable to respond to a big expansion in demand post-Covid. The poor economic performance of major coffee importers after Covid and high arabica prices after the Brazil frost in 2021 stimulated a big shift towards cheaper, more robusta-intensive blends around the world.

The biggest shift was in Brazil, where robusta moved from around a 55% share of internal demand towards an 80% share- a big increase in a market estimated at over 20 million bags.

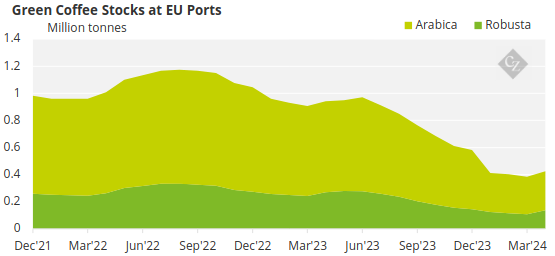

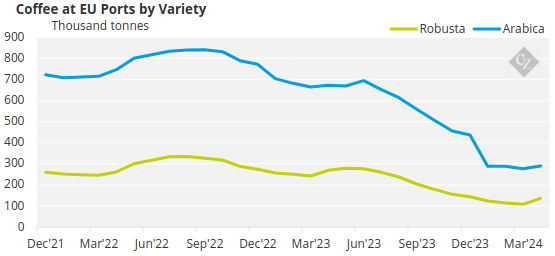

The robusta share of green coffee imports into the EU increased from around 32% pre-Covid to a high of 38% in the 12 months to September 2023.

Source: ECF

Any growth in coffee demand post-Covid was also concentrated in developing coffee markets where consumers tend to prefer soluble and more robusta-intensive roast coffees.

The increased demand hollowed out robustas stocks. At origin, the carry-over stocks held by the foreign trade in Ho Chi Minh City were at their lowest level in living memory coming into the current coffee year. There also now seems to be no coffee available up-country among farmers in Vietnam.

In importing markets, ECF statistics show that robusta stocks in European ports halved in the 12 months to April. Robusta certified stocks declined by 770,000 bags to 400,000 bags in the 12 months to end-February 2024, their lowest level in eight years.

Source: ECF

Certs have increased to 780,000 bags as of the end of May, but this increase does not seem to reflect the underlying tightness of robusta supply in importing markets.

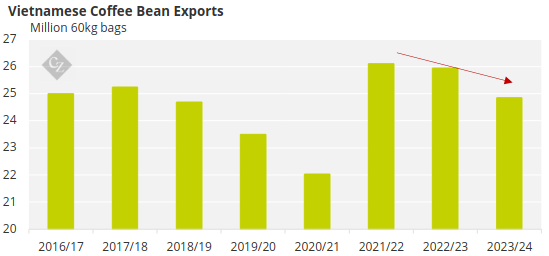

Vietnamese Production Declines

The days of production growth in Vietnam, which accounted for over 50% of origin green robusta exports in 2023, are over, with the government clampdown on any expansion into forested areas and the farmer increasingly multicropping with more profitable products such as durian.

Source: USDA

The extreme hot, dry weather in Vietnam between January and mid-May, which depleted irrigation sources, has created concerns that the 2024/25 crop may be damaged. This is a real worry as every single bean of Vietnamese coffee is needed by roasters. Things are so tight that traders are actively looking for robustas to import into Vietnam and Indonesia.

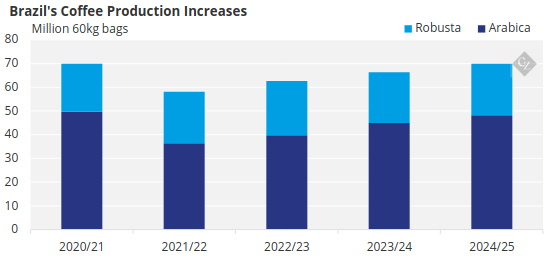

Brazil is the only country in the short run that has the potential for large scale increases in robusta production due to replanting at higher tree densities and some area expansion.

Source: USDA

Unfortunately, Brazil robustas (conilons) have not reached full production potential in the last three crop years due to cyclical and climatic reasons. The first arrivals from the new conilon crop, which traditionally starts after the Easter holidays, suggests that the 2024/25 crop will also be disappointing due to the extreme hot, dry weather in the conilon region between November and January as the beans were developing.

Concluding Thoughts

There are no easy solutions near-term to the tightness in the robusta market.

The next Vietnamese crop will not be available in bulk until November. Brazil robusta supply to the international market will also be constrained by logistical problems and internal demand from soluble manufacturers and domestic roasters.

It looks like demand shifts will have to do the heavy lifting with roasters using more arabicas in their blends.

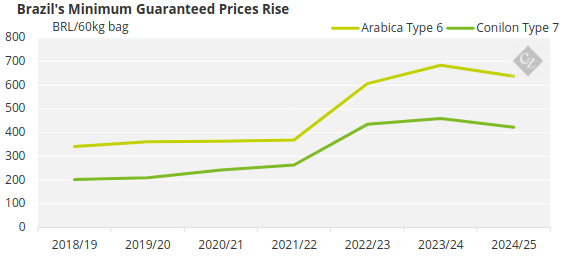

There is already a substantial move towards increased robusta usage in Brazil, where some low quality arabicas are cheaper than conilons. The shift is also happening in importing markets, but it appears to be slower than expected.

Source: USDA

The better yields using robustas in soluble production is a big barrier to replacement by arabicas. Roasters are also reluctant to replace robustas in their blends with arabicas coffees that over the longer term have usually been more expensive.

The job of the market, either through the futures price or through differentials, appears to encourage this substitution to bring both the robusta and arabica markets into a more stable balance.