Insight Focus

- War has removed top two sunflower oil exporters from the market.

- Oilseed supply was already tight after drought in Canada cut 7m tonnes of production.

- South American crop failures have reduced supply this season.

The USDA summed up recent global vegetable oil developments as all negative for global production in the March version of Oilseeds: World Markets and Trade.

Many traders have asked me my views on price potentials for world vegetable oils and the impact of the Ukrainian and Russian war developments on world balance sheets.

Per the paragraph above, the USDA notes three major impacts to the global vegetable oil balance sheets, two of which unfolded before the events in Ukraine: last year’s Canadian drought, which cost canola seed growers 7m tonnes of production (3.5m tonnes of canola oil equivalent) from peak estimates, this year’s loss of 10m tonnes (15?) of production between Brazil, Argentina, and Paraguayan peak estimates (1.8m tonnes of soybean oil equivalent), and now the issues in the Black Sea with significant question marks for the two major sunflower oil origins, Ukraine, the largest in the world, and Russia, the second largest in the world, collectively accounting 60% of global production.

The world’s vegetable oil balance sheet was tightening prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the possibility of significant interruption to the sunflower

agronomic cycle of planting, fertilisation, pollination, harvest, and processing. Moving forward, traders must make estimates of just how poor outcomes in Ukraine may get and the evolving impact to the global balance sheet.

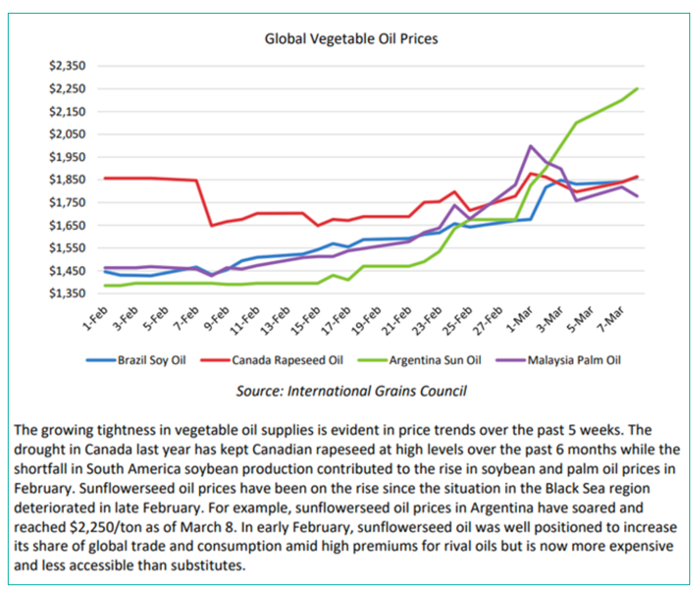

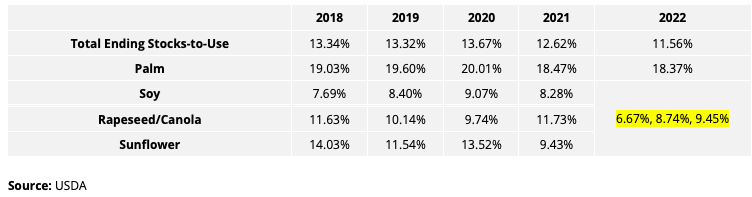

As noted above, global ending stocks-to-use ratios for the four major vegetable oils, palm, soy, rapeseed/canola, and sunflower have continued to trend lower over the last five years, driven by flattening palm production (did the second largest producer, Malaysia, achieve peak production in 2019?), weather impacts to rapeseed/canola, and expanding domestic usage of vegetable oil for biodiesel (Indonesia) and renewable diesel (USA). The below table shows the declining trend:

A declining stocks-to-use ratio for the major global vegetable oils in the midst of a policy driven, radical step higher in demand for vegetable oils, renewable diesel in the USA, and biodiesel in Indonesia, portends that the declining trend in available stocks-to-use will likely continue into 2023. This could accelerate if Ukrainian sunflower seed production (planting, fertilising, stewardship) fails to meet the average trend exasperated by reductions or interruptions to processing capacity (labour, power, transport).

How to change course and stabilise the ending stocks to use ratio to more comfortable levels and generate mean reversion in vegetable oil prices — is that even possible in a world of higher prices for all commodities especially petroleum? I will leave that to the economists to work out and assume that global inflation heads higher and the function of markets is to stabilise the price movement, albeit at higher-than-average prices in the coming years. Stocks-to-use is a ratio so an increase in stocks, a decrease in usage, or some combination of a change in both components can achieve an increase in the ratio.

An increase in stocks would likely be a function of much higher production as well a small reduction in consumption. I don’t see either happening in the very near future. The first scenario for an increase in stocks comes from expanded production of oilseed crops in the Northern Hemisphere.

The 2022 Southern Hemisphere production cycle has nearly ended with some recent improvement in Argentine soybean production via late rains in the crop’s agronomic cycle that can still prove to be very beneficial. That benefit will be measured in 1m tonnes more soybeans than the USDA recently forecasted but may be offset by an equal or greater loss in Brazil and Paraguay due to drought during the key agronomic cycles in those crop lands.

So, it’s up to the Northern Hemisphere to produce an above average crop in soybeans and rapeseed/canola. Let’s see. Current dry conditions in both the US and Canada remain a concern.

What about a decrease in demand to send the ratio higher? Here, I struggle to think through any scenario that curtails demand during the single largest increase in domestic demand for vegetable oil – demand from the US renewable diesel industry. Renewable diesel will consume nearly 2b pounds more soybean oil in the second half of the year than it did a year ago, a 40% increase. What stops that or even slows that? Again, I do not know.

Policy remains firmly in place although Reuters recently published a story suggesting the Biden administration may reconsider renewable fuels policy but that means more hydrocarbon consumption versus renewable fuels, and have politically driven policy makers thought that implication through? Will “green” members of Biden’s party accept greater hydrocarbon usage? Fuel policy reconfiguration or abandonment takes time and is not a quick fix. Could the food sector slow consumption? Maybe. Could there be a global movement away from vegetable oils to alternative dairy and animal fats? Maybe there too.

What to do? First and foremost, pray for peace. Next, ration demand for vegetable oils on the presumption things will not go well in Ukraine (prepare for the worst, pray for the best).

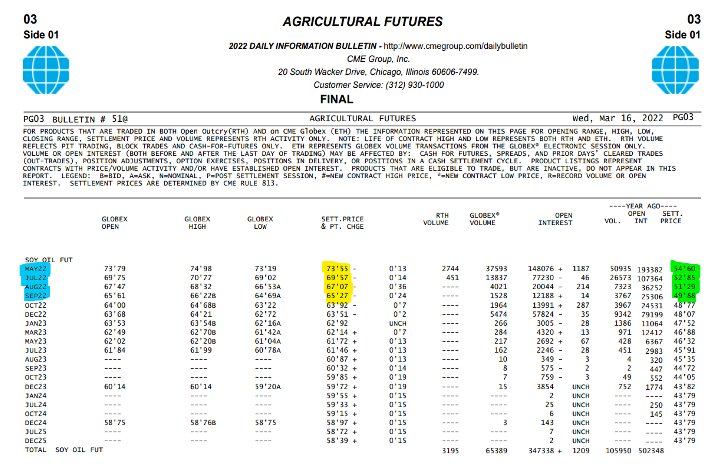

Let’s look at the vegetable oil market construction today via the Chicago Mercantile Exchange’s soybean oil futures contract, the global hedging mechanism for most players, to see the economic signals the price curve is sending.

Blue highlights the first four active futures contracts. Yellow highlights the first four futures prices for the May, July, August, and September 2022 contracts. And green highlights the first four futures prices for the May, July, August, and September 2021 contracts.

What can we observe?

- 2022 nearby (May) price at $.7355 per pound versus $.5460 per pound a year ago, 35% higher.

- 2022 deferred (September) at $.6527 per pound versus $.4988 per pound a year ago, 30% higher.

- 2022 May-September spread at $.0828 per pound inverse (backwardation).

- 2021 May – September spread at $.0472 per pound inverse (backwardation).

Market forces are rationing in two parts. Firstly, through sharply higher prices versus a year ago, and secondly via steeper inverses in spot (May) versus deferred (September) prices, increasing the penalties for those that may hoard vegetable oils with higher prices today and lower prices in the future.

Have these higher prices and steeper inverses curtailed demand? Is there evidence that these prices have started to erode demand? Not that I can see.

What are the implications for this? Still higher prices, still steeper inverses? Yes, likely.

What about deferred prices that today are sharply lower than the spot? Those prices likely roll up to the spot price as those deferred futures move forward in time and become the present. What’s the probability of that? Quite high, over 70%.

Any chance of a nearby mean reversion event? I’m sure there is a scenario that might develop quickly, I just cannot think of it. The scenario that develops more slowly, because it is a policy change, is some adjustment or pause to the US renewable energy policy. Likely? Less than 40% chance.

Concluding Thoughts

- High spot prices are here to stay for the foreseeable future.

- Deferred prices represent good value for the consumer.

- A prolonged step function to higher prices has occurred and remains in place for the foreseeable.

- If significant global rationing must occur due to a crop loss in the Ukraine (or anywhere in the Northern hemisphere), another step function to higher levels must take place as draconian demand rationing will need to occur.

For further information, please email waltercronin@msn.com.

Other Insights That May Be of Interest…