Insight Focus

- There are a few well-established production pathways for SAF.

- However, these come with their own benefits and disadvantages.

- More pathways are being approved but scale is proving to be a challenge.

We are progressing well with the subject of SAF with brief accounts of why it’s made, how it’s made and what it contains. This week we’re looking at where you can get hold of it and why this simple matter appears rather problematic.

Most SAF Produced from Mature Pathways

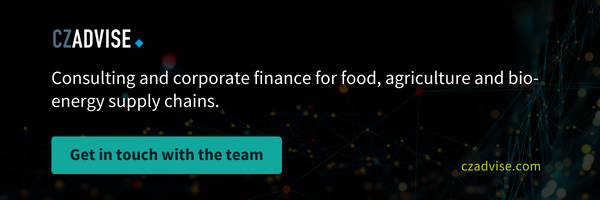

First, if you want to buy synthetic aviation fuel, the best place in the world is South Africa, where it has been made for decades and approved the longest. Indeed, it explains why the first Annex in D7566 is the Fischer Tropsch (FT) pathway.

It was introduced to enable jet fuel from coal to get into the pipeline to Johannesburg airport. However, as we learnt earlier, not all synthetic aviation fuel is sustainable, so the sustainability benefit would be zero – or even negative.

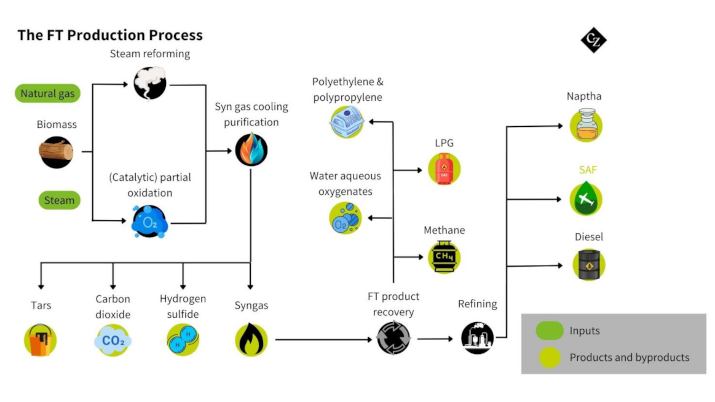

For sustainable aviation fuel we need to turn to the next pathway — Annex A2. This is the Hydrogenated Esters and Fatty Acids (HEFA) process, which is also a mature technology. It has great penetration around the world and, relative to the remaining pathways, good availability.

In the short term, this process is going to provide the world with most of its SAF with significant processing centres in Europe and Asia. In the US there is a great deal of activity across many sites and, while scale-up is on the horizon, availability at present is in its infancy.

For the remaining technical pathways, it’s more a question of future production rather than current availability. Customers are queuing up to buy SAF, but the manufacturing capacity is struggling to keep up.

Challenges Emerge

Why are we in this position of imbalance? It’s a difficult question to find a simple answer to. There are eight technical pathways with various processing routes and feedstocks and so there is no shortage of technology and innovation that have been harnessed.

It is highly likely that there will be more pathways approved in the short term and so the technical authorities have proven that jet fuel can be made in many ways with the final product meeting the original specifications – truly, a drop-in fuel.

But this apparently slow start in terms of availability is driven by several factors. Firstly, scaling up new technologies can be difficult and time-consuming, and SAF production is no exception. Costs can produce a headwind, too. Alternative products, in particular renewable diesel, which is more straightforward to manufacture, can also prevent the growth of SAF availability. Other factors, including processing reliability and feedstock availability and consistency, can be troublesome.

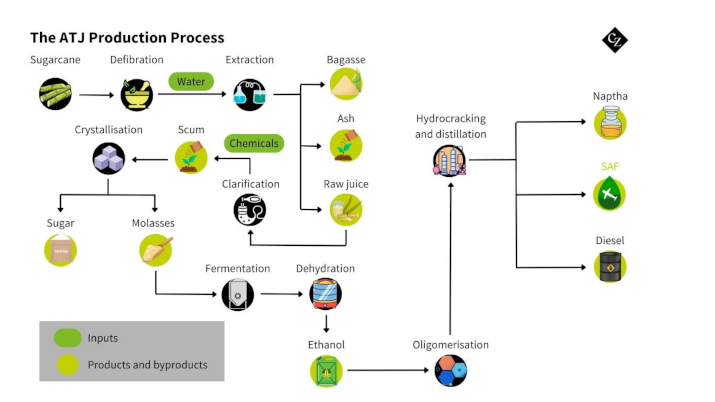

ATJ Most Promising Pathway

Altogether, the production of SAF via the Alcohol-to-Jet process (Annex A4), offers most promise of scale with fewest ripples in feedstock and processing.

So, for the time being, if the plane you’re on is running on SAF, it is likely to be a low percentage and almost certainly started life as a vegetable oil. But this will change, the percentage will grow, and the provenance of the sustainable component will vary.

Next time we’ll look at why different SAFs have different levels of environmental benefit, how this is calculated and who you can trust with the numbers.