Insight Focus

- One of the biggest themes for the shipping industry in the 2020s is decarbonisation

- IMO regulations have come into force this year to promote lower emissions.

- But CII – one of the key measures – seems to exacerbate emissions rather than reduce them.

CII, or Carbon Intensity Index, applies to vessels over 5,000 gross tonnes and came into force on January 1. As the name suggests, this measure focuses on the intensity of a vessel’s pollution based on its capacity and distance travelled.

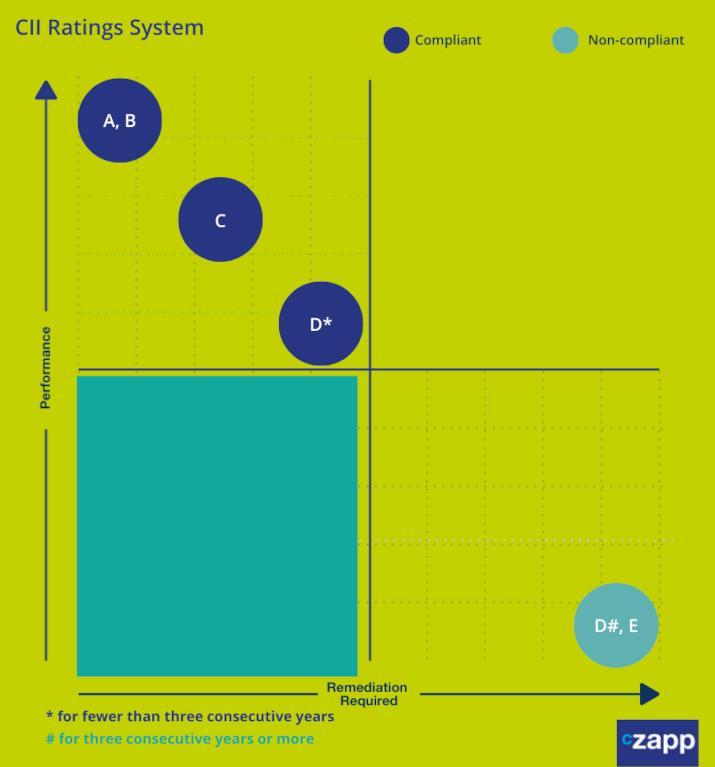

The ratings range from A (least emissions intensive) to E (most emissions intensive) but each threshold will change to become stricter towards 2030. This encourages continuous improvements on efficiency among vessels and voyages.

The CII rating system is ongoing and vessel owners should compare the Actual Attained Annual Operational CII against the Required Annual Operational CII every year.

As part of the CII, all vessels will need to prepare a Ship Energy Efficiency Management Plan (SEEMP) and keep it on board the vessel. This document should contain the methodology used to calculate the ship’s Attained Annual Operational CII, as well as a plan of how it plans to achieve the Required Annual Operational CII for the next three years.

As it stands, non-compliant ships can continue sailing during 2023 if remediation efforts are being carried out, but after December 31, they risk being detained or fined.

How is CII Calculated?

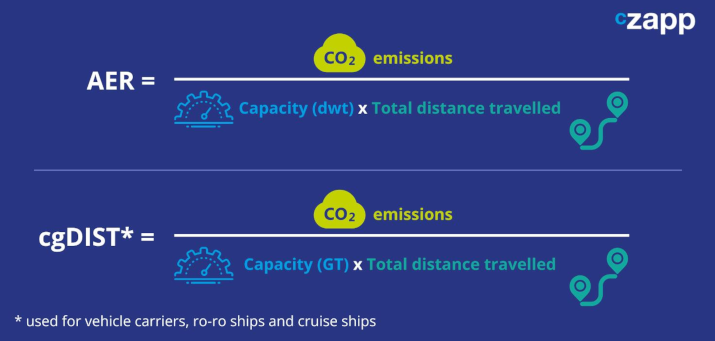

A ship’s CII involves an extremely complex calculation that considers a range of factors, including the ship’s power, speed and fuel consumption. The final figure should give an idea of the vessel’s CO2 emissions per tonne of cargo over a nautical mile.

A much-simplified version of the calculations can be found below.

Efficiency is Compromised

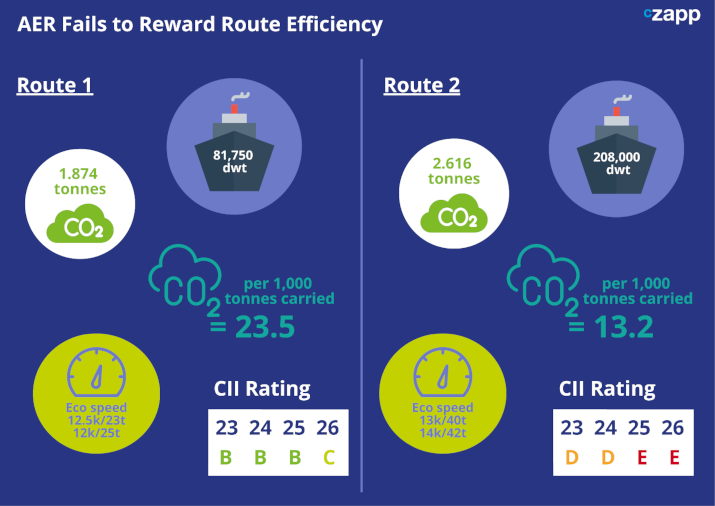

Larger ships are generally considered to be more energy efficient due to the greater volumes they can transport. Logically, it would seem more sensible to transport 160,000 tonnes rather than to make two 80,000-tonne trips.

However, the AER calculation fails to take into account CO2 emissions per 1,000 tonnes carried. This means that larger ships carrying heavier loads are likely to be punished by the system. An example is shown below.

Data source: Oldendorff

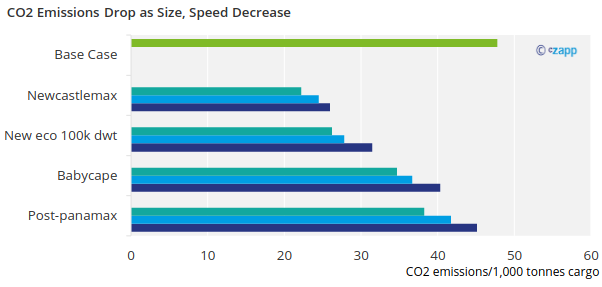

The industry also has a problem with the measure of CO2 emissions. Slower moving vessels are lower emitting, meaning more capacity will get tied up as charterers and owners are incentivized to slow down. This could impact profitability for shipping firms and charterers.

Source: Oldendorff

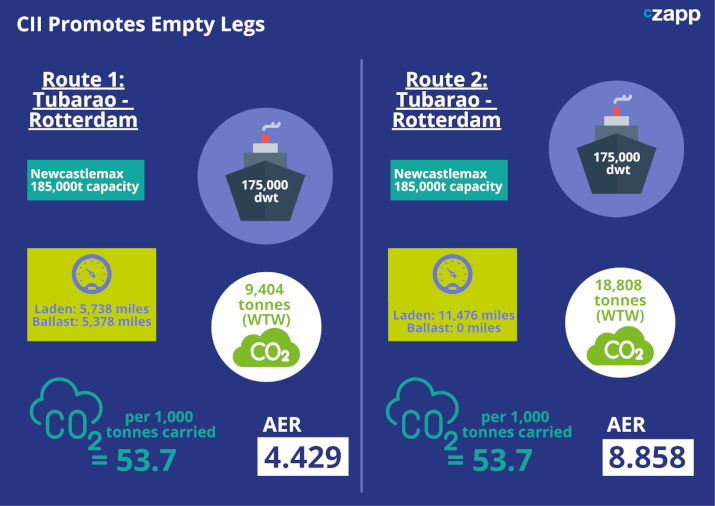

Another issue the CII calculation doesn’t seem to take into account is the efficiency of ballast and laden legs. The current methodology seems to promote empty leg voyages. In fact, the best CII rating is obtained by slow steaming in ballast all year round.

Note: Calculations use CO2 and mileage calculations from Carbon Care

Oldendorff has even found that vessels rated in the D and E categories can halt trading and spend a portion of the year ballasting to repair their rating.

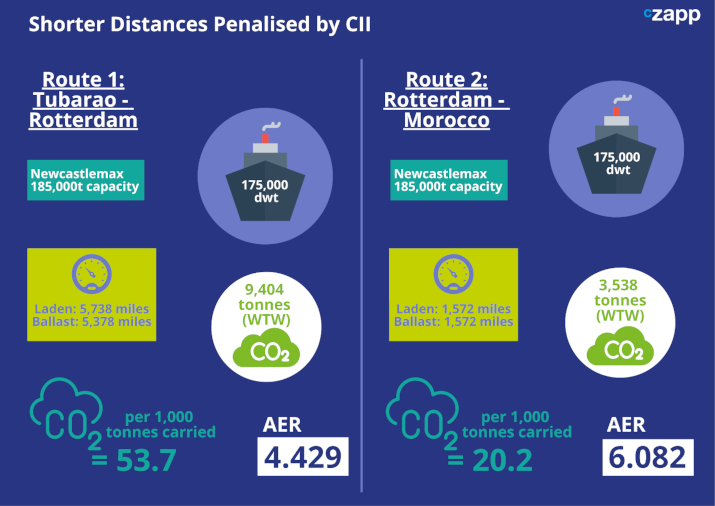

Distance Matters

The CII calculations as they stand also penalise shorter distances. This can be seen in the following example.

Note: Calculations use CO2 and mileage calculations from Carbon Care

These requirements could mean that higher-emitting ships will be allocated to longer voyages, effectively creating more emissions. Lower-emitting ships would likely be assigned to shorter voyages. In the short term, this is likely to increase CO2 emissions rather than lower them.

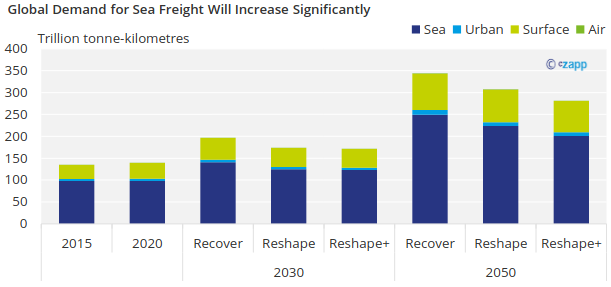

Another concern is that, as time goes on, the global vessel fleet will grow. Reducing emissions by 70% based on a 2008 baseline will be complicated by demand growth. By 2050, global sea freight demand could increase by as much as 155% compared to 2020.

Note: Recover, Reshape and Reshape+ refer to the three scenarios modelled by OECD’s ITF Transport Outlook

Source: OECD

Transhipments Will Suffer

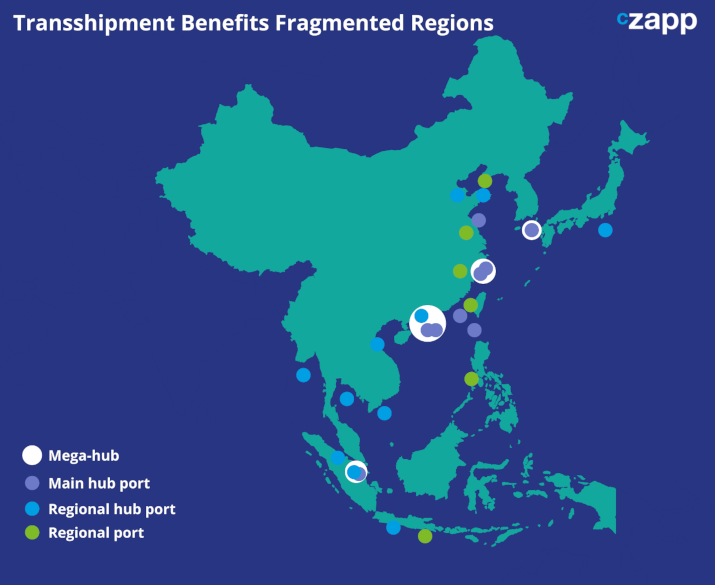

The global shipping industry works like the aviation industry in that not all ports have direct connections. Likewise, some are not large enough to welcome the largest ships or perhaps low tide means a certain port is temporarily unavailable. In these instances, a connection point is needed – known as a transshipment hub.

An example of port structures in the far east can be seen below, highlighting the need for transshipment.

However, CII does not take transshipment vessels into consideration through its methodology. These vessels can appear to consume a lot of fuel over small distances and therefore pull down the CII rating.

Employment Issues Surface

Compliance with the CII regulations ultimately lies with the shipowners but when it comes to time-chartered vessels, charterers have also been dragged into the fray.

Owners of time-chartered vessels must comply with the charterer’s employment orders, but these could impact the CII rating of the vessel. Owners may decide to slow steam, modify cargo capacity or deviate routes to comply with the CII, but this could also mean they breach their charter and could be liable for damages.

This is especially true if these decisions result in delays to the voyage, which breaches their obligation to proceed with utmost despatch. To address these issues, BIMCO has drafted a clause to be used in contracts that splits responsibility between the owners and charterers. The parties must agree on a CII and the charterer should take steps to ensure the voyage’s emissions do not exceed this agreed level.

There have however been complaints that this clause is not balanced for both parties. Critics argue that it places responsibility for compliance with the charterer, while the owner has the right to interfere with the voyage.

Some Issues Are Outside Shipowner Control

There are many more considerations to be taken into account when it comes to CII ratings. Some issues are likely to arise that will impact CII ratings if they are not taken into account within calculations. These include:

- weather routing

- hull dynamics

- vessel speed

- port stay turnaround time

- vessel idling

- carbon intensity of the fuel

- availability at chokepoints (i.e. Panama and Suez canals)

- seasonal congestion

The industry argues that an unfair environment is being created by these factors and they should be taken into account through the calculations.

Concluding Thoughts

- This kind of regulation is groundbreaking and so teething problems are to be expected.

- It is only after a few years of operation that some issues can be identified and rectified.

- That is why there is a grace period for reporting and remediation.

- But as it stands, some of the facets of CII will exacerbate emission rather than reducing them.

- There is no easy solution but trial and error.

- In the meantime, Oldendorff encourages shipowners to focus less on the rating letters and more on efforts to reduce real emissions.