Insight Focus

Smuggling is a huge problem for the cocoa markets. Due to uneven pricing dynamics in neighbouring countries, smuggling can be financially lucrative and is exacerbating the current cocoa price rally.

Last month, we identified the 5 factors the cocoa industry should monitor – one of which was smuggling. Here, we take a look at why smuggling is such an issue and how it impacts on the global cocoa price.

Price Setting Plays Role in Smuggling

Smuggling in the world of cocoa mainly involves Ivory Coast and Ghana because they are government-run origins with farmgate prices set in advance of the season in October, although both systems differ slightly.

Normally, the price of cocoa is established from selling the next season’s crop a year forward. The average combined level of sales then establishes the average FOB price, which then generates the farmgate price, having deducted the costs, taxes and margins (bareme) between shipment and farmgate.

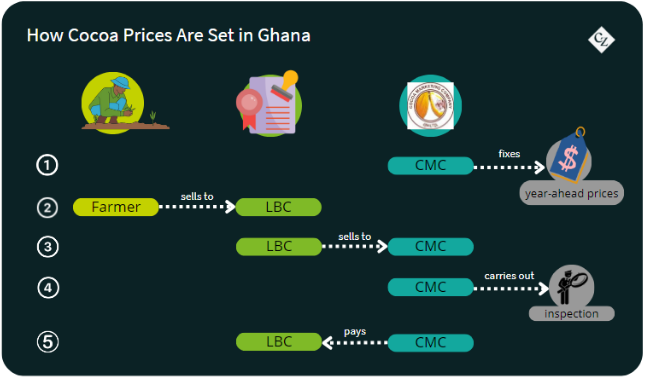

In Ghana, a Cocoa Marketing Company (CMC) exists under the cocoa regulator (Cocobod). This acts as a direct counterparty to the cocoa buyers from consuming countries by fixing outright prices a year forward.

The farmers sell to licensed buying companies (LBC) who in turn sell to CMC. All the cocoa is delivered to CMC managed and controlled warehouses in the ports. The LBCs are paid for their deliveries after inspection and acceptance into the port warehouse.

The system in Ivory Coast is based on matching buyers and sellers at a predefined price set on a periodic basis, which might vary daily or weekly, in a form of exchange. The farmers sell to either co-ops or middlemen called traitants, who in turn deliver to shippers at the port. Co-ops and traitants can also be shippers, or the shippers can be either local or multinational companies.

The different systems can generate different outcome for prices for farmers in Ghana and Ivory Coast in any given season. If there are differences in prices between Ivory Coast and Ghana (as well as neighbouring countries like Togo, Sierra Leone, Liberia or Guinea), the difference can be enough to create a margin for smugglers.

Smuggling Exacerbates Supply Issues

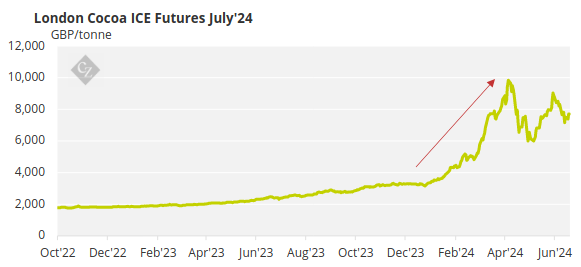

Ivory Coast and Ghana both sold a year forward for the 2023/24 crop in a slightly backwardated market at prices that generated approximate farm gate levels of USD 1,550/tonne. As the season progressed, the world market price relentlessly climbed to record highs in April 2024, generating huge smuggling opportunities.

This is because the neighbouring countries’ pricing is based on prevailing spot market, with an estimated 75,000 tonnes being smuggled from Ghana alone. Similar challenges exist for Ivory Coast but estimated volumes are not clear.

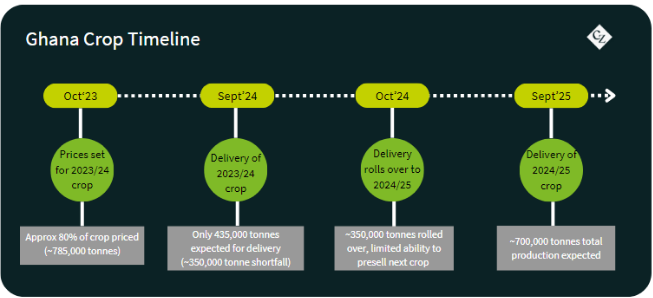

This smuggling has exacerbated the problems of a severely reduced crop in both origins. The smuggled volume leads to a reduction in revenues for the country and greater difficulty in fulfilling outstanding contracts. This leads to defaults and contracts having to be rolled to the 2024/25 crop.

The Importance of Data

Part of the challenge for regulators and industry is to estimate the volume of the crop. During the growth of the crop, there are pod counting teams carrying out advance research and forecasting. One of the parameters that is closely monitored is the arrivals at the ports of Ivory Coast and Ghana. These numbers can then be checked for alignment with the previous forecasting as the actual crop starts to arrive at the ports.

Source: IStock

This approach can be significantly disrupted if smuggling hides volumes exiting the country, thus creating a disparity between the actual tree crop and port arrivals, and eventually the exports from the country. The realignment can only come after assessment of neighbouring countries’ export data to establish if there have been abnormal increases above the historical export levels. With the entry into force of the European Union Deforestation Regulation (EUDR), smuggled cocoa will not be able to be placed on the EU market from the date of entry into application, which is December 30 this year.

This means any smuggled main crop from October 2024 coming from Ghana and Ivory Coast will not be compliant to EUDR and cannot be legally landed in Europe. This is a market with 60% of global production crossing its customs borders.

But will the smugglers care?… Probably not!

What’s Next for Ivory Coast and Ghana?

Both countries will announce their farmgate prices in October 2024 for the 2024/25 crop. The 2023/24 maincrop in both countries reached a farmgate price of approximately USD 1,550 give or take currency movements.

As already observed, this created smuggling out to neighbouring countries but not really between the Ivory Coast and Ghana. The price was raised in both origins to approximately USD 2,450 for the mid-crop, which was very low volume, thus generating very little impact.

Both countries have had to roll contracts from the prior crop to the 2024/25 crop, but Ghana has had to roll a higher percentage over, leaving little room for higher priced sales to boost farmgate prices. Ivory Coast would appear to have more wiggle room and therefore more relative ability to sell at higher levels with less proportionate carry over commitment.

If this divergence in their relative positions creates higher prices in Ivory Coast than in Ghana, then the financial opportunity to smuggle from Ghana will take place not just to third party countries still benefiting from high spot prices but also to Ivory Coast.

An additional challenge that may rear its ugly head is the availability of finance in Ghana to pay for the crop at farm gate level. If CMC cannot make seed fund available to the license buying companies (LBC), then the normal banking channels will be required but may be reluctant to jump in in this incredibly uncertain and volatile cocoa world.

If the cocoa starts to get stuck up-country because the supply chains are not fuelled with cash, then there will be much more incentive to smuggle to where the money is. This scenario is hard to predict but certainly needs monitoring in an environment where the market’s movements have created huge liabilities between counterparties, which will inevitably bring reluctance to increase those liabilities.