In the first three reports of this series, we set out a framework for Sustainable Agriculture (SA) in a global environmental context and introduced the concept of Sustainable Intensive Agriculture (SIA), which looks to add an additional component; that of improving yields.

We’ll now consider the types of schemes and certifications available for SA.

Minimum Requirements

Although there is no all-encompassing definition of SA, the US National Agricultural Research and Teaching Policy Act of 1977 provides a simple definition of SA.

These would be a minimum requirement for any existing or aspiring SA scheme and there are many embellishments in current schemes.

For example, food safety is covered under “quality of life” but is often expanded.

Identifiable Core Participants in Schemes

The number of companies, associations and certifiers has grown rapidly from around 2000. It is possible to identify some common threads through the agricultural supply chain.

(1) Associations.

These are normally non-profit organisations, but their composition, often described as stakeholders, and their aims and methods, are diverse. There are also several hundred of them. Stakeholders can come from areas such as farming, food and agribusiness companies, retail, civil societies, government and academia.

It’s very important, if considering joining an association, that there are like-minded or commercially similar members within it. Members are normally published, so this is not a difficult task. For example, Field to Market (US) and Sustainable Agriculture Initiative (SAI, Belgium) have a significant representation of food and beverage manufacturers, and Cool Farm Alliance is supported by UK supermarkets Tesco and Marks & Spencer. All these associations have a role to play and a diverse membership prevents a specific interest group from gaining control.

Many associations also have detailed mission statements and are the catalyst for a wide variety of certification or accreditation schemes, laying out the protocols for these in conjunction with Good Agricultural Practices (GAP).

There is a general consensus among associations that the entry bar to an SA scheme should not be set too high and many offer subsequent recognition for improvements, such as from beginner to accomplished, or bronze up to platinum.

(2) General Certification and Inspection Companies (CI)

These companies are numerous and are employed to carry out the measurement and conformance with the protocols. In many cases, the farmer is asked to fill out a self-assessment and then the CI company will send a representative to the farm to verify the data. Direct input missing out this step face-to-face in conjunction with the farmer does have relevance.

This can be useful, for example, in instances where the farmer has had only minimal education. It can also happen when the farmer doesn’t know the answer as farmers also have stakeholders in their operations. Records of operations may sometimes be held by a contractor or an agronomist attached to a local farm store. CI verification is challenging and technical, especially where barrier stakeholders exist, some of which may fear a loss of sales by their perception of SA. This is one reason why many CI companies offer education programmes as part of their package.

Not every farmer may wish to be certified. Farmers, in particular, may want to benchmark against others and check they are following GAP as a matter of belief (inspection without certification).

(3) Specialist CI Companies

Some CI companies specialise in single or small groups of commodities or are focused, not just on farms, but on a larger part of the agricultural supply-chain. Examples of such would be UTZ/Rain Forest Alliance (tea, coffee, cocoa and hazelnuts), Round Table on Sustainable Palm Oil, and Czarnikow VIVE (sugar).

There are some CI companies that focus on specific groups such as very small farms in the developing world that can’t easily become certified.

(4) Specific Needs

These companies tend to specialise in advanced calculations of the carbon footprint which relates to SA. A few years ago, I was the project manager for an NGO in the US who wanted to calculate the environmental and sustainability profile of the sorghum crop (specifically the kg CO2e/ bushel). This had not been done before, but similar data for other crops, such as wheat and maize (corn), had been gathered.

The data was important to the US EPA and Department of Energy, especially with reference to bio-ethanol production and relative green certification in the US and Europe. This involved recruiting several hundred farmers and tracking data (by internet) for all the annual energy uses on the farm. All included inputs such as seed, fertilizer, energy for irrigation (where used), fuel, etc. Then, sophisticated mathematical conversion formulae were used.

This project took 16 months to produce just one headline number. This is why many SA schemes stick to more simple measurements and focus on continuous improvement and avoid an excessive burden of proof. Nevertheless, SA schemes need to be measurable.

(5) Retailers and Consumers

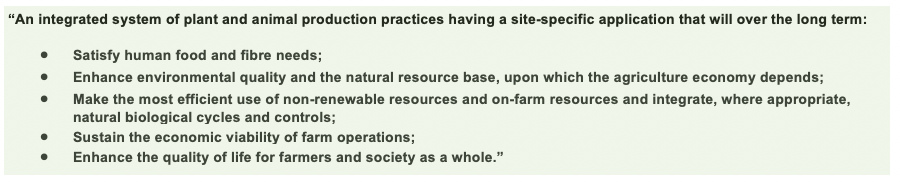

While there is a reasonable structure for, say, buyers in an SA world, retailers and consumers at the end of the supply-chain face some very specific challenges. Having spent several decades battling with nutritional labelling and safe supply-chains, there is now a new and complex issue to deal with. Yet, a 2019 YouGov survey in seven European countries found that 67% of consumers support a label relating to a commitment to measure and reduce carbon footprint.

One issue is how to engage and educate their customers. In the much shorter supply-chain of farmers’ markets, consumers and farmers can meet and be educated face-to-face by the producer. Another is that packaging materials also have a sustainability component (usually more related to forestry than agriculture).

Consumers are currently confused and need help. On one leading search engine, only 22% of the ‘sustainable agricultural certification labels’ produced were specifically related to SA in its whole form (or mentioned it). The rest was a jumble of confusing images, some which related partly to SA, and some that bore little or no relevance.

The Ecolabel Index currently lists 456 ecolabels, many related to food and those are just for those that are serious about ecology. There are many others that are intended to deceive.

Imagine as a busy, but environmentally conscious, shopper, you are buying groceries on the way home. You don’t have a lot of time to look and read all the labels, including the nutritional ones. Which of the labels below are holistic SA certification schemes?

(The answer is at the end).

Single-Ingredient and Multi-Ingredient Labelling

It may be fine to offer a finished product for ale derived sustainably from a single source such as rice, fruit, vegetables, fish and meat. But what about those that have lost identity preservation?

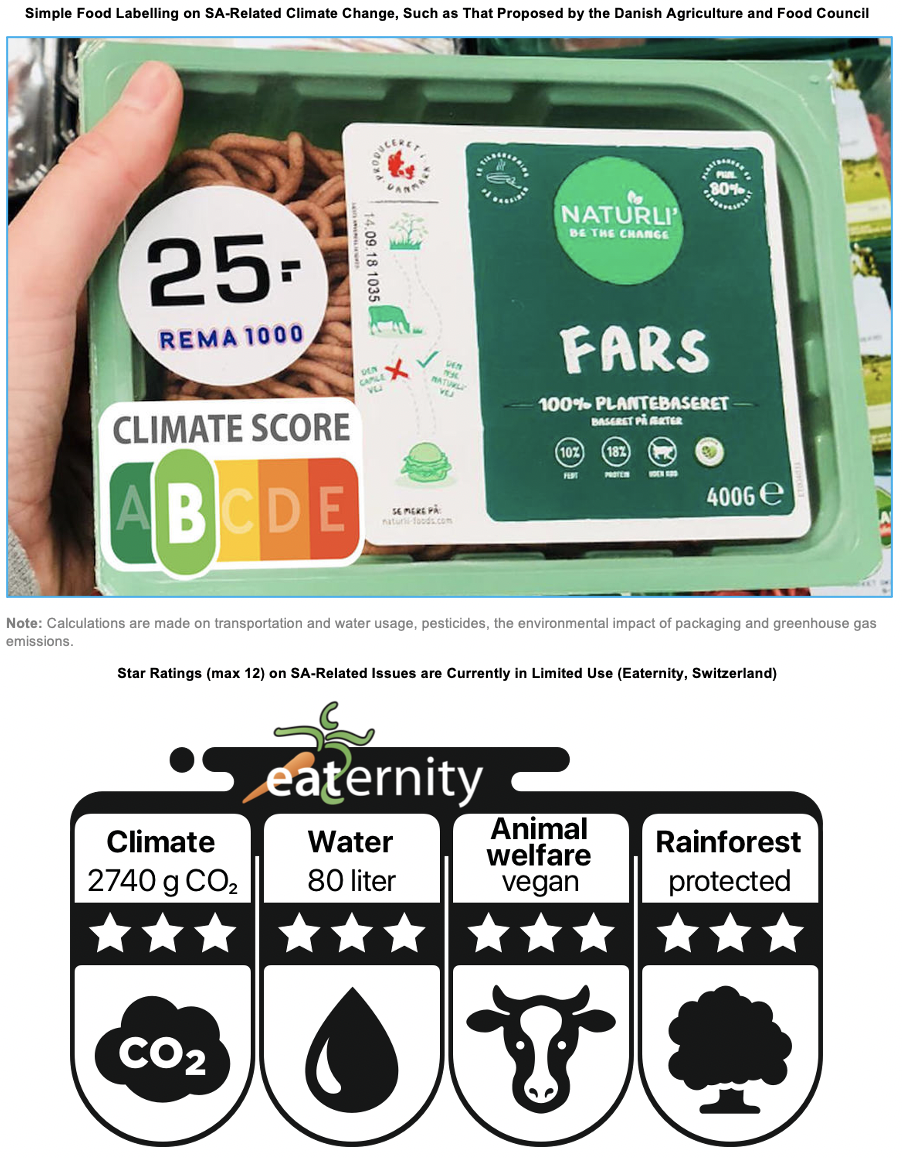

Many products on sale have multiple ingredients. What if, say, 40% can be sourced sustainably and 60% can’t? How do we accurately demonstrate to confused consumers that an offering of mixed ingredients is sustainably produced and packaged? The answer may lie in a relative measure, as shown below for single product foods.

In the future, is it possible that multi-ingredient products could be certified with plus points for sustainable ingredients and minus points for those that are not, to produce an aggregated and independently verified score? Denamark certainly thinks so.

Oh, and the answer to quiz was C.

Other Opinions You Might Be Interested In…