Insight Focus

- The aviation industry is responsible for about 2% of global energy-related CO2 emissions.

- In order to reduce impacts, companies have been looking to sustainable aviation fuel (SAF).

- But how far along are we in the SAF journey?

An Intro to Sustainable Aviation Fuel

Welcome to our first post in a series on SAF that aims to share insights into sustainability in aviation fuel. It’s written with the generalist in mind, but we hope with enough bite for the professional to have the occasional ‘ah-hah’ moment.

They’ll be posted a couple of times a month for the foreseeable future – feedback welcome so do get in touch.

For the first missive, we thought we’d start at the beginning.

What is SAF?

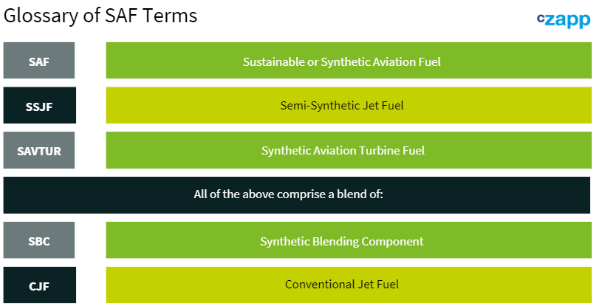

SAF stands for Sustainable Aviation Fuel – although not always. Sometimes it stands for Synthetic Aviation Fuel. We’ll cover this apparent confusion in later posts when we dive into definitions, including the raft of other terms for SAF.

But suffice it to say that all Sustainable Aviation Fuel is Synthetic Aviation Fuel but not all synthetic fuel is sustainable. For example, jet fuel made from coal by the renowned Fischer-Tropsch process is synthetic but not sustainable. Meanwhile, jet fuel made from CO2 and green hydrogen is both, and jet fuel made from crude oil is neither.

Why SAF?

So why are we bothered about SAF? Sustainability is the key. We’ll explain this by looking at 10 numbers. No graphs, no Venn diagrams, no fancy stuff – just 10 numbers:

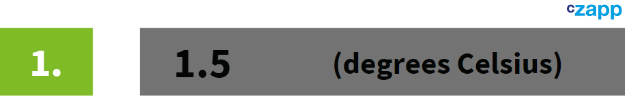

This is what the sensible world wants to see as the maximum limit of the rise of the world’s atmospheric temperature. It doesn’t sound much but it really is, and its impact is massive, so it’s important not to exceed this. We’re currently around 1.1 degrees Celsius so it’s possible, although unlikely, that 1.5 degrees won’t be exceeded. But to get there, we have to do a lot.

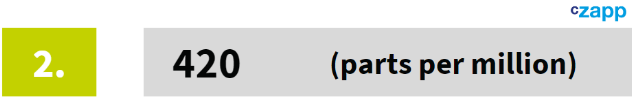

The concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere, at the moment, although it’s climbing. CO2 concentration was around 280ppm before the Industrial Revolution kicked off in the late 18th century. This is important because CO2 is the most significant greenhouse gas, responsible for the rise in global temperatures. While other gases are more effective at raising the atmospheric temperature, they tend to be present in much lower concentrations.

The amount of CO2 the Aviation Industry emits every year. To achieve (1) we need to reduce (2) and to reduce (2) we need to reduce (3). Simple.

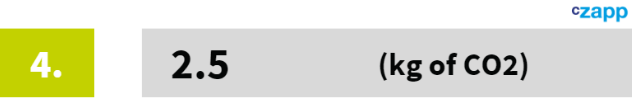

This is what each litre of jet fuel produces when burnt. This includes conventional, sustainable and synthetic jet fuels. In other words, for the same aeroplane carrying the same load on the same route, the amount of CO2 emitted is the same, more or less.

If we want to reduce the amount of CO2 produced by aviation, we have to look at the process of making the fuel – and use fuels that take CO2 out of the atmosphere in their production. This is the cornerstone of sustainability in aviation.

The number approved by the specification authorities to create synthetic jet fuel from non-conventional sources. This will climb, and very quickly, we think. So, there are plenty of choices. If you can’t get hold of any SAF, it’s not because the chemists and specification authorities have been sitting on their hands.

The maximum percentage of synthetic component allowed to be blended with CJF to produce SAF. Take care though – 2 of the pathways from (5) are limited to 10%, and indeed one is permitted up to 100%.

Percentage of jet fuel globally that is sustainable – we really are at the dawn of this new age.

The percentage of sustainable component in a jet fuel that permits the vendor to call the fuel sustainable. Crazy, but true.

The number of airports around the world where SAF may be blended. Up until now, blending at airports is not allowed.

The probability of CJF being entirely replaced by SAF by 2050.

These numbers, some factual some opinion, begin to paint the picture of the SAF landscape. Later in the series, we will go into some more detail.

In the next post later this month we will address the questions ‘What is SAF?’ and ‘What are the differences between SAF and CJF?’