- The use of land is an area in which the EU Farm to Fork policy makes tangible, measurable pledges.

- It aims to reach a 30% objective in protected land (or conservation areas) by 2030.

- It also pledges that 25% of agricultural land must be permanently converted to organic practices, from the 8% currently in organic production.

The EU’s Farm to Fork strategy was launched in May 2020 under the framework of the European Green Deal.

The strategy sets out several pledges and targets for the European Union to reach by 2030 with the goal of creating a more sustainable, environmentally friendly food value chain.

While some proposals are more concrete than others, the Farm to Fork strategy is an ambitious plan but it has invited some criticism.

Over this eight-part series, we aim to provide you with a greater understanding of the policy’s implications and how it’ll affect your day-to-day business.

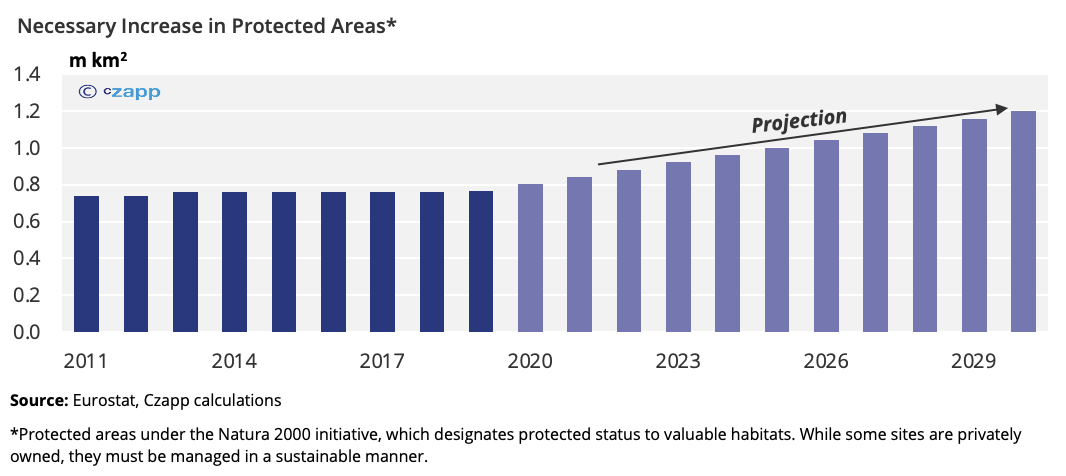

Increase in Protected Land Area

The amount of land protected under conservation efforts in the EU has stalled in recent years, according to official data on Natura 2000 protected areas.

From 2011 to 2019, protected land increased by just 23,000km2 – or at a rate of about 0.4% per year. It’s also worth noting that the largest increase in protected area was seen in 2013, when Croatia joined the bloc. When discounting this event, the growth rate shrinks to just 0.07% per year.

To reach the goal of increasing protected areas to 30% of total land, this would require a growth of over 57% on 2019 levels, or over 5% per year. In the 10 years from 2020 to 2030, protected land would need to increase by almost 40,000km2 per year, compared with an average of just 576km2 per year on average between 2013 and 2019.

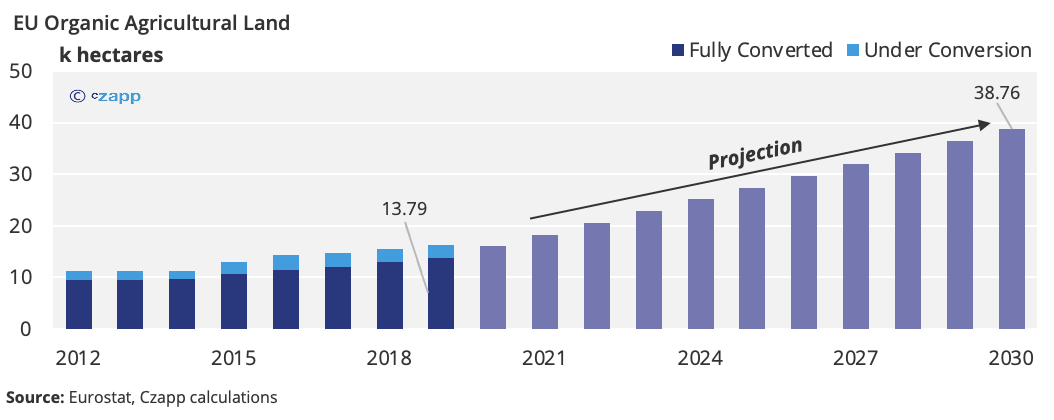

Increase in Organic Land Use

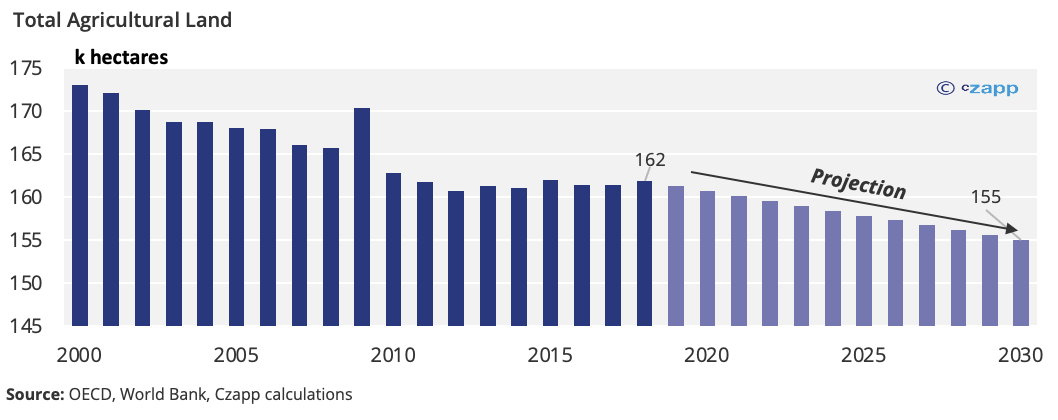

The Farm to Fork policy pledges to increase land used for organic agriculture from 8% to 25% of total agricultural land. If agricultural land continues to shrink at the same rate of around 0.36% per year in the EU, there should be around 115m hectares by 2030.

Using the 2030 assumption of 155m hectares of total agricultural land, 25% of this equates to 38.8m hectares.

This means, to meet the organic land target, the EU would need to see growth of about 2.27m hectares per year. Prior growth from 2012 to 2018 has averaged just 619k hectares per year.

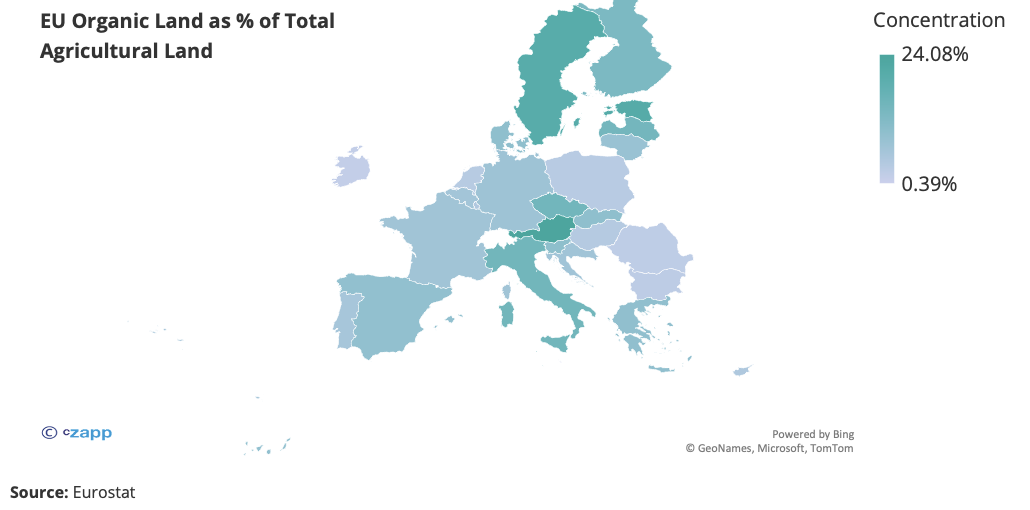

Most of existing agricultural land conversion has focused on Western and Southern Europe, with highest concentration in France, Spain, and Italy. But as a proportion of total agricultural area, the highest organic agricultural land use is in Austria, Sweden and Estonia, followed by Italy, Latvia, the Czech Republic and Cyprus.

Just 0.39% of Malta’s agricultural land uses organic practices, followed by 1.65% of land in Ireland and 3.92% of land in Hungary.

This uneven distribution means that, to reach targets, organic farms will likely be concentrated in certain countries unless there’s a concerted effort to address the lack of organic practices across Eastern Europe.

The Cost of Organic

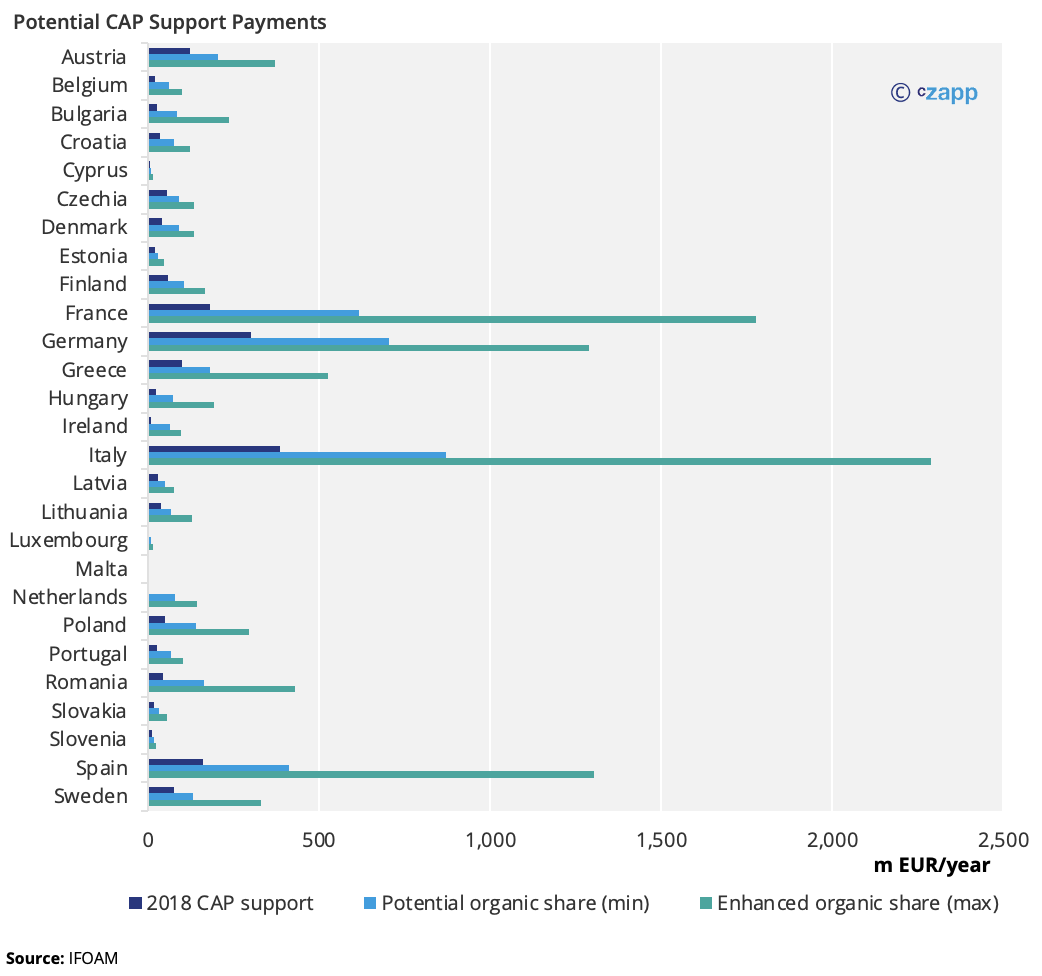

As well as yields, the cost of the conversion to organic is also a consideration. IFOAM mapped potential future organic payments based on 2018 Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) funding.

Using two metrics – the potential organic share and the enhanced organic share – the organization found that if the EU-27 were to increase organic farmland to 21.1% of all farmland, total payments could go up to €4.4 billion, while an increase to 25% would require funding of about €10.4 billion.

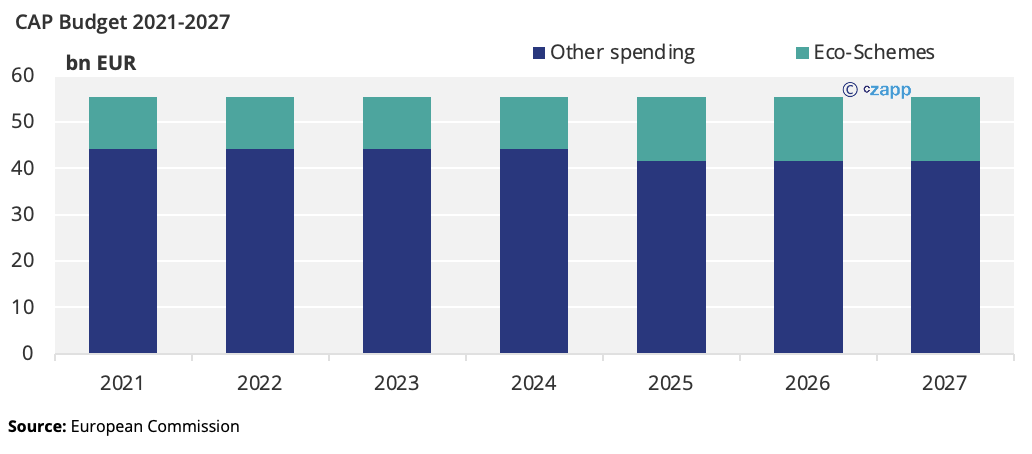

But this is largely in line with the European Commission’s 2021-2027 CAP budget. This month, the European Parliament approved a budget of €387 billion over the seven-year period, equating to a total of around €55.28 billion per year. Of this, there’s a requirement to spend at least 20% on eco-schemes to 2024, increasing to 25% from 2025. This would mean an initial budget of just over €11 billion for eco-schemes, which would then rise to €13.82 billion.

The concept of the eco-scheme lacks definition but can apply to restoration of wetlands, CO2 absorbing techniques or organic farming.

Is Organic Viable on a Large Scale?

A global study (2012) comparing yields from conventional farming and organic farming found that organic yields were 80% of conventional yields on average. The evidence from the study also suggests that, as organic farming is scaled up, this yield gap increases even more substantially.

Another global study on the financial competitiveness of organic agriculture conducted in 2015 found that, without organic premiums, both the benefit/cost ratios and net present values of organic farms were significantly lower than a conventional farm. However, when organic premiums were applied, organic agriculture was between 22% and 35% more profitable and the benefit/cost ratio exceeded those of traditional farms by 20-24%.

Emissions Reduction

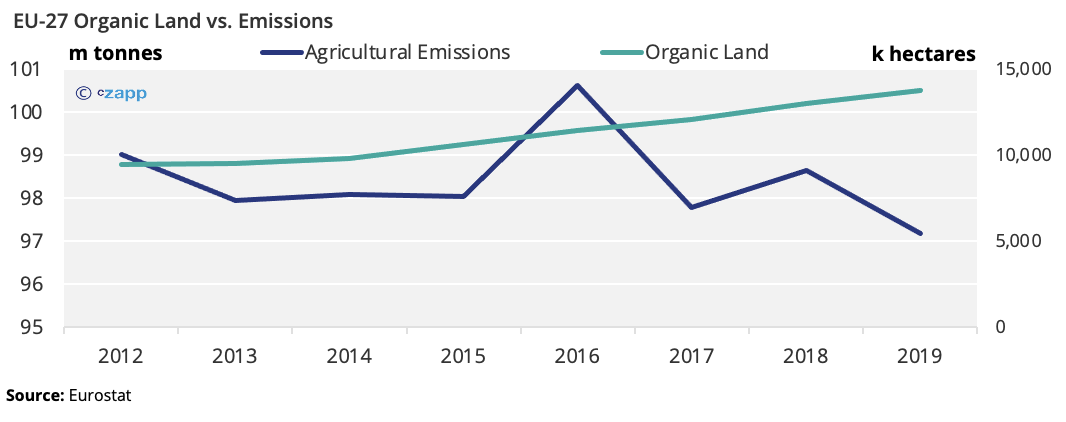

The Farm to Fork policy related to land use could lead to a reduction in agricultural emissions within the EU but the European Court of Auditors has warned that the potential impacts are unclear.

Although, on a total basis, emissions have dropped by about 3.5m tonnes since 2012, there have been several spikes, despite an increase in organic land.

It’s also worth noting that any potential decrease in emissions may be offset by an increase in third-party emissions, should the bloc become a net importer. This will be covered in more depth on another edition of Czapp’s Farm to Fork series.

Appetite for Change

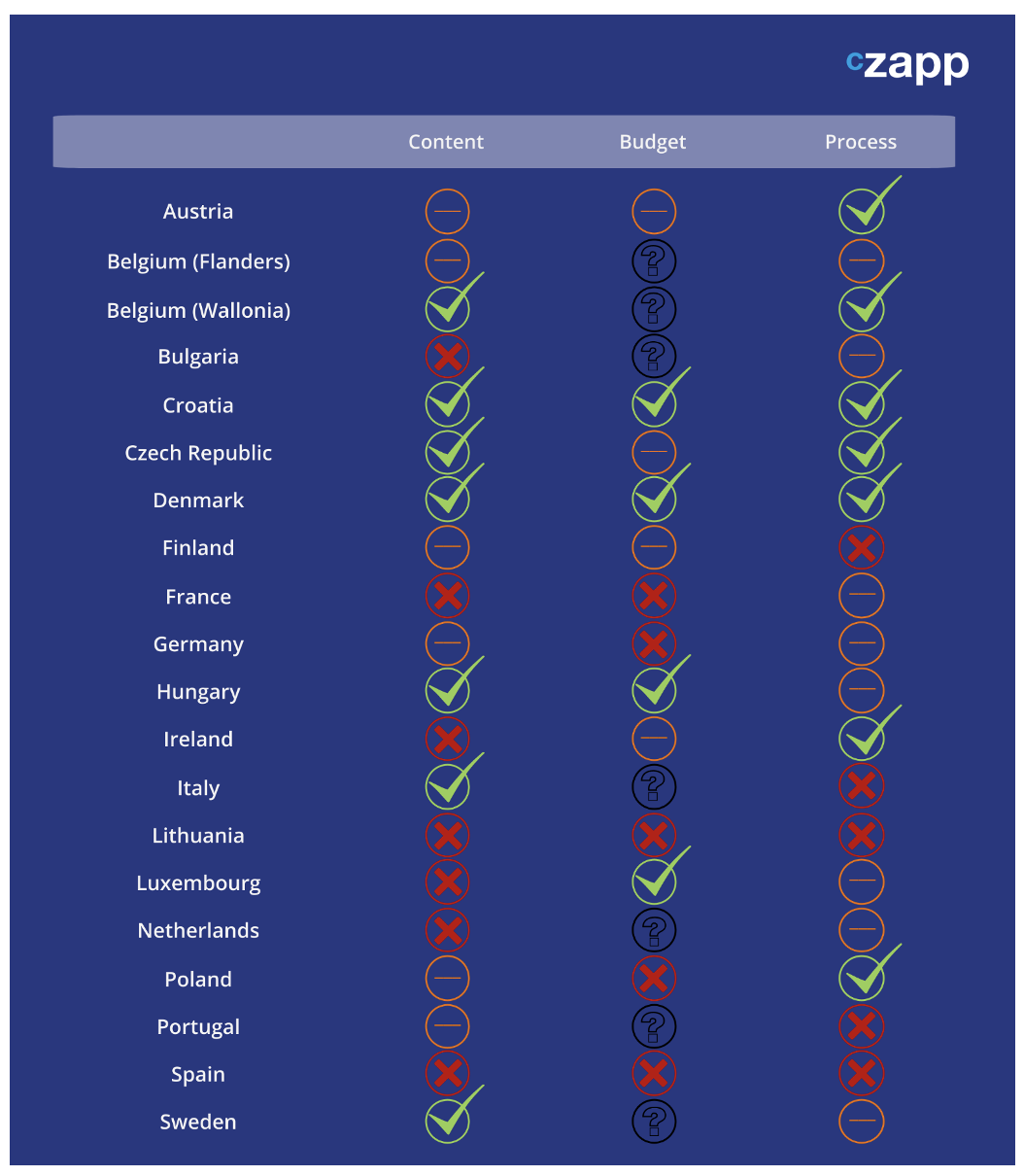

Finally, a switch to organic farming requires the appetite for change. There have been several pledges made by member states with varying degrees of commitment to the Farm to Fork policy. The International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements (IFOAM) ranked commitments. No sufficient information was received to evaluate the situation in Cyprus, Estonia, Greece, Latvia, Malta, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia.

There’s some discord between the member states in relation to their organic ambitions. For example, Austria has set the target of 30% of organic land use by 2030, although its current organic land use is around 26%.

Other countries, such as Bulgaria, have not yet started the process of presenting plans or budgets. Spain’s consultation process also involves exclusively conventional farmer organisations.

The full ranking and methodology can be found here.

Other Insights That May Be of Interest…