- As part of the Farm to Fork strategy, the EU has made commitments to fishing.

- It’ll bring EU fish stocks to sustainable levels, enhance traceability, and promote farmed fish and seafood.

- If the EU can attain the goals, sustainable fishing practices could boost incomes through greater productivity and reduced waste.

The European Union’s Farm to Fork strategy was launched in May 2020 under the framework of the European Green Deal.

The strategy sets out several pledges and targets for the EU to reach by 2030 with the goal of creating a more sustainable, environmentally friendly food value chain.

While some proposals are more specific than others, the Farm to Fork strategy is an ambitious plan but it has invited some criticism. Over this eight-part series, we aim to provide you with a greater understanding of the policy’s implications and how it might affect your day-to-day business.

Fish and Seafood Consumption

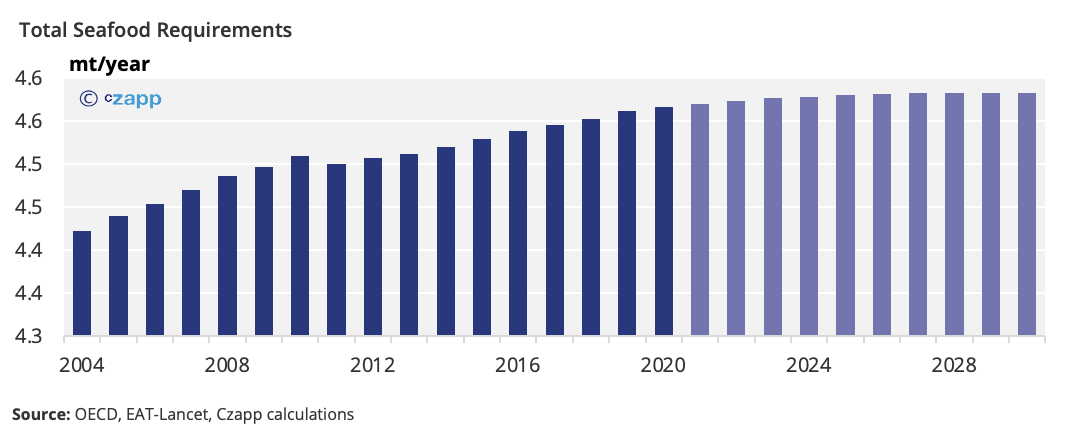

According to EAT-Lancet recommendations, the ideal intake of fish and seafood is around 196g per person per week, equating to about 10.2kg per person per year. This would bring total dietary requirements to around 4.5m tonnes per year for the EU – a figure that should plateau to 2030 given the estimated slowdown in population growth.

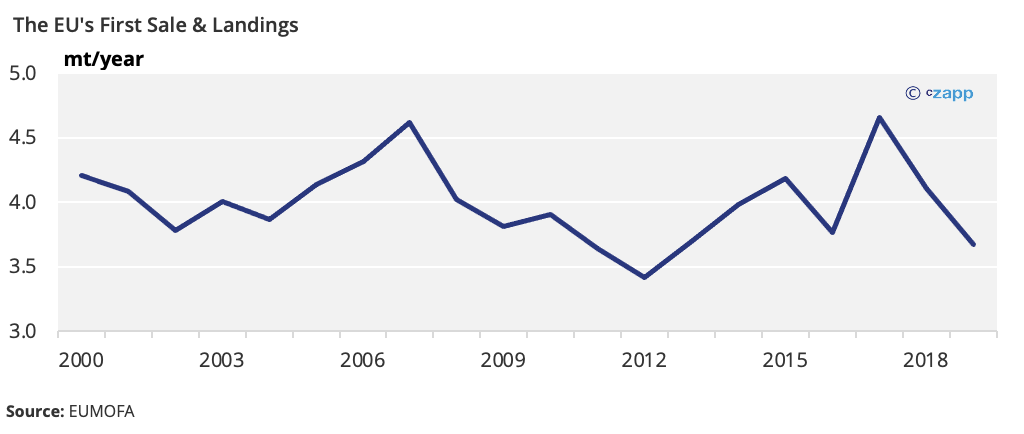

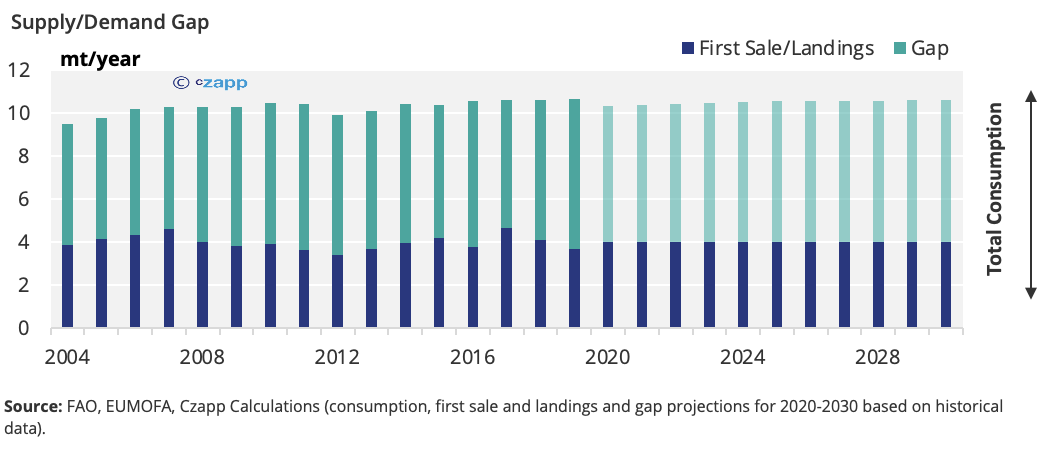

Even if the EU were consuming fish at the recommended rate, there would not be nearly enough seafood caught by EU countries to satisfy demand. From 2000 to 2019, the average total EU landings and first sales came in at around 4m tonnes per year.

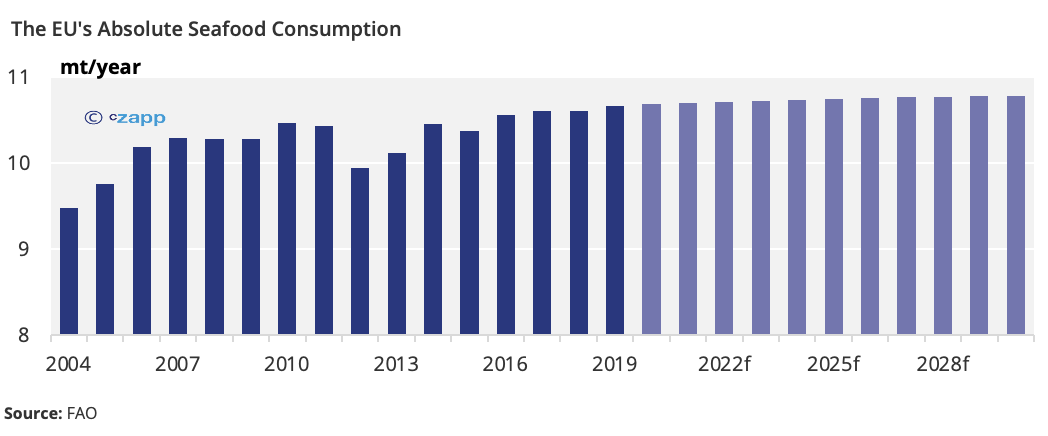

This also doesn’t account for the fact that current EU fish consumption is more than double the recommended amount per person at about 23kg per person per year. If consumption continues to increase at historical rates, the EU will have to supply 10.7m tonnes of fish and seafood every year by 2030.

This means that if consumption continues to grow at current levels and EU fishing rates remain stable, the shortfall between supply and demand could reach about 6.8m tonnes by 2030.

Aquaculture

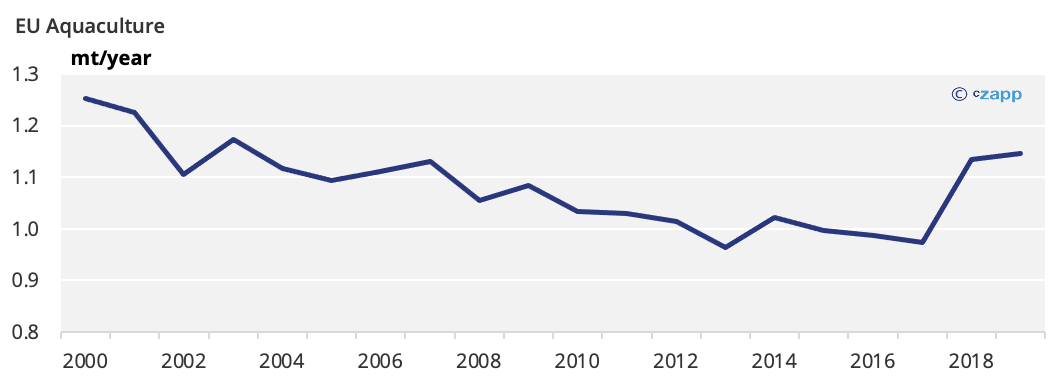

Some of the EU’s fishing shortfall has typically been supplemented by aquaculture. An average of just over 1m tonnes of seafood is cultivated for yearly consumption in the EU through aquaculture, bringing the supply-demand shortfall to just shy of 6m tonnes.

One of the EU’s goals through the Farm to Fork strategy is to promote farmed fish and seafood. But just how feasible will that be?

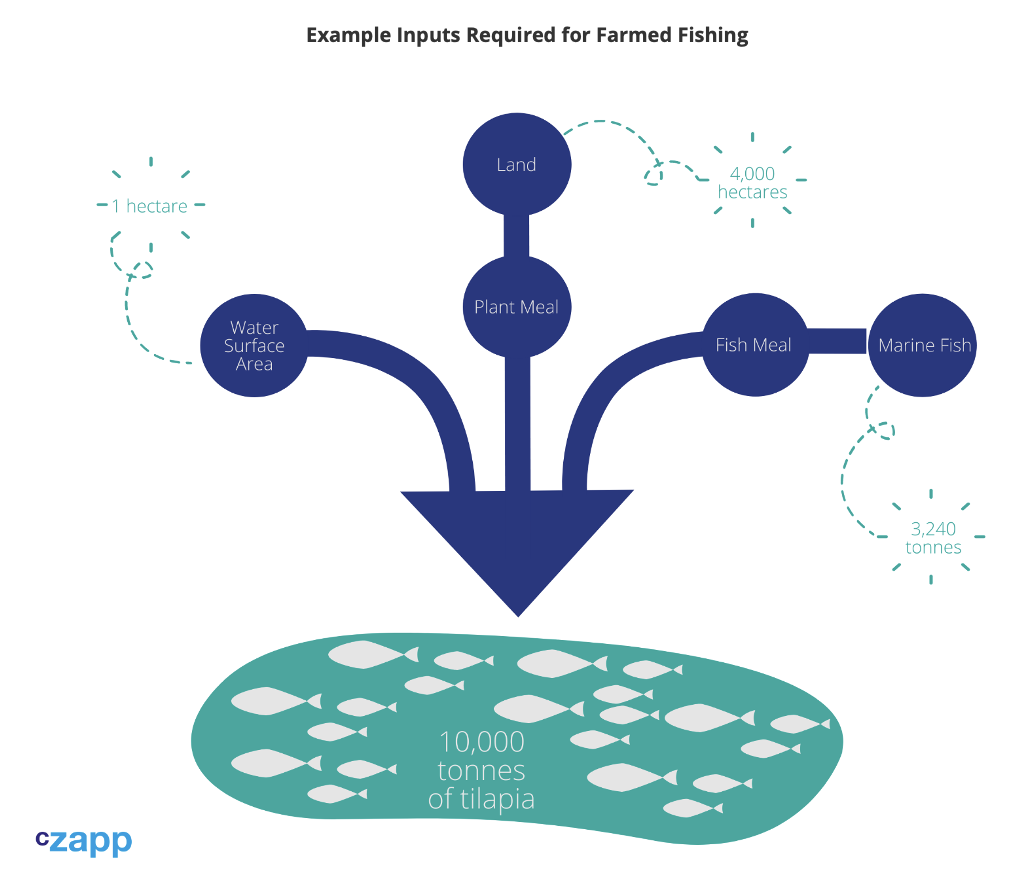

It’s difficult to predict on a general basis how much land is needed to expand aquaculture to a level that may sustain seafood consumption in the EU. This is because requirements vary based on several factors, including the species cultivated, the feedstocks used and the size of the farm.

While some species can be farmed in high-density environments, land requirements for the plant ingredients in fish feed rivals those of swine and poultry.

Transparency

The EU tracks illegal fishing in third countries. Only marine fishery products accompanied by catch certificates validated by the competent flag state can be imported into the EU. The traffic light-style system first issues a warning to non-compliant countries before issuing a ban on the import of produce from the country in question if it’s still found to be in non-compliance.

Currently, Cambodia, Comoros and St Vincent, and the Grenadines are listed as non-compliant countries. Cameroon, Ecuador, Liberia, Sierra Leone, St Kitts and Nevis, Trinidad and Tobago and Vietnam all have been issued with warnings.

Through the Farm to Fork strategy, the EU wants to increase transparency by promoting the use of digital catch certificates, bolstered by the existing CATCH system. Under the current system, non-EU countries are not bound by the rules on catch certificates, although a revision of the Fisheries Control Regulation proposes that the system should be made mandatory for EU importers. This would mean any third country wishing to sell seafood to the EU would most likely come under pressure to join the CATCH system.

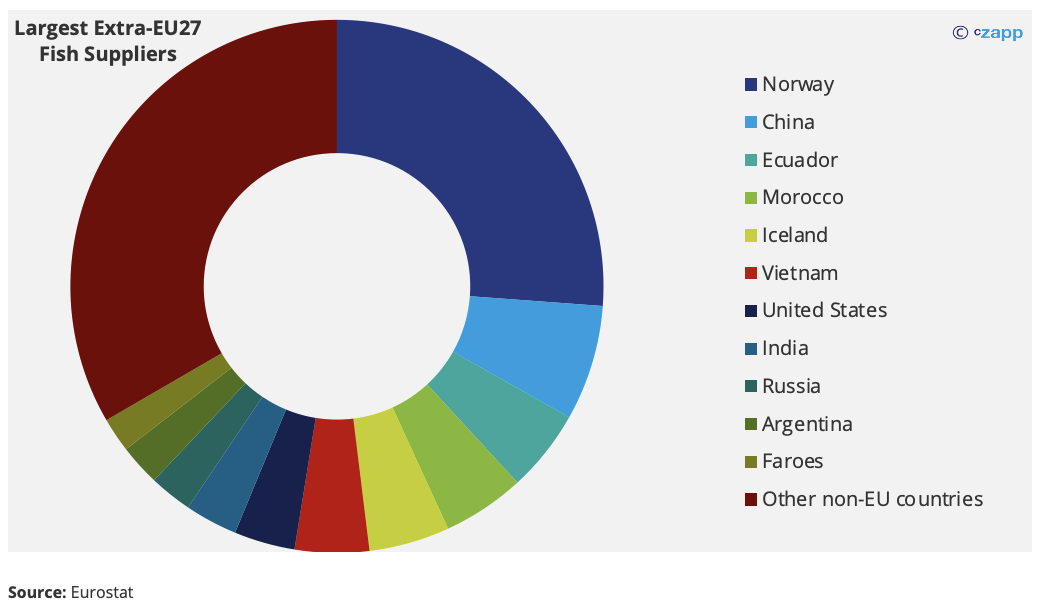

Norway is the EU’s largest fish supplier, providing 26.2% of extra-EU imports, while China provides about 7% and both Ecuador and Morocco sell 5% to the EU per year.

Import and Export

The EU secures about half of its fish supply through third country imports. According to EUMOFA, in 2020, over 5m tonnes of seafood was imported to the EU from third countries, while it exported just over 2m tonnes.

Although a reduction in imports may seem like one way to make the EU’s fish supply more sustainable, the quantity of fish landed in the bloc is not enough to sustain its demand. To cut out imports, the EU would have to double traditional fishing catches or increase its aquaculture production by five-fold. This may not be the most efficient production method given the danger of overfishing in the seas surrounding the bloc an considering the land use needs of aquaculture.

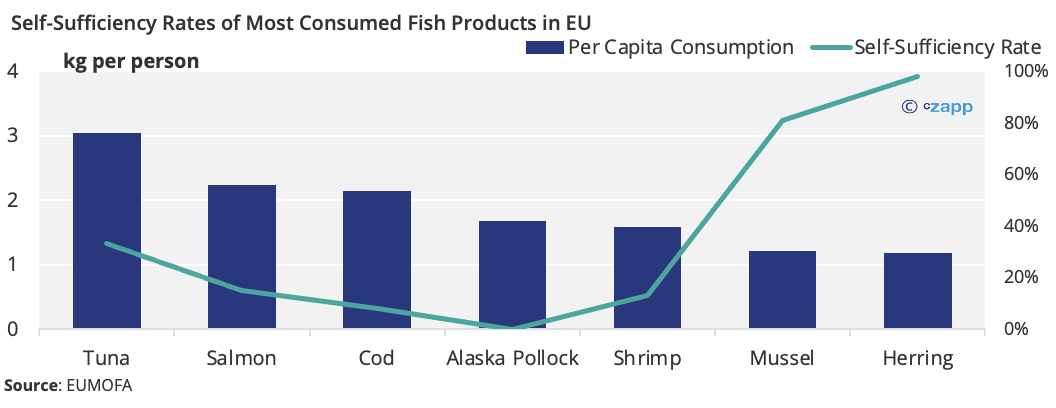

There’s also the consideration that the type of fish in demand in the EU is not necessarily available in its own waters. The seven most popular fish species – tuna, salmon, cod, pollock, shrimp, mussels and herring — account for over 50% of European consumption. The single most popular, tuna, accounts for 13% of total apparent consumption in the EU but the bloc has only a 33% self-sufficiency rate – meaning it must source 66% of its tuna needs elsewhere.

EU Quotas

The current EU quota system is complex and covers over 200 commercial fish stocks. The system uses Total Allowable Catch (TAC) numbers for each species across various management areas. The TAC for the first quarter of 2022 was agreed in December with most of the quotas reduced on the previous year. The final TAC for the first quarter was reduced to about 1.2m units from 1.9m unis in the same period of 2021.

The quota system also factors in a minimum landing size (MLS), which reduces waste by specifying a minimum size per species. Fish that are smaller than the MLS cannot be sold for human consumption, which provides a strong incentive for fisherman not to target smaller, more immature fish.

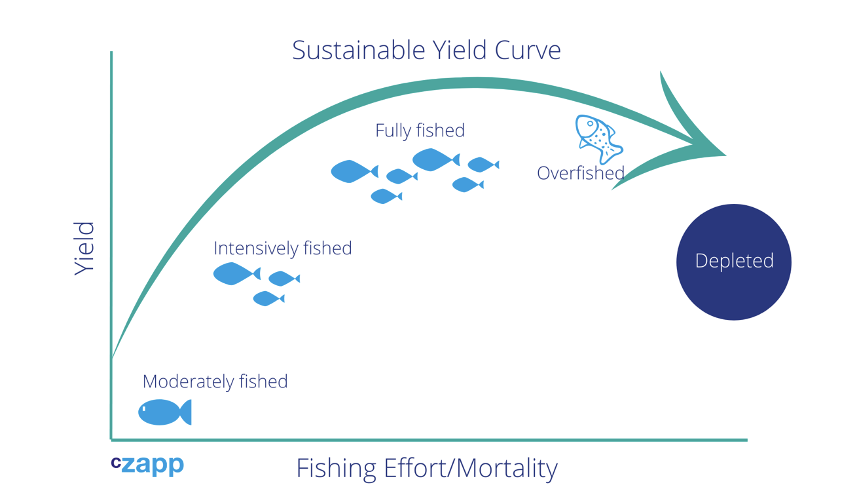

TACs are developed through maximum sustainable yield projections. These calculations set out the maximum fishing of any given species before there is a risk of overfishing. The aim is to strike the delicate balance of maximising fishing while avoiding overfishing.

The MSY was adopted in the EU for a number of reasons. Firstly, it allows the bloc’s industry to be more competitive globally and reduce dependence on imports, while remaining sustainable. Secondly, it’s designed to create greater efficiency, incentivizing large-scale and high-value catches and disincentivizing discards.

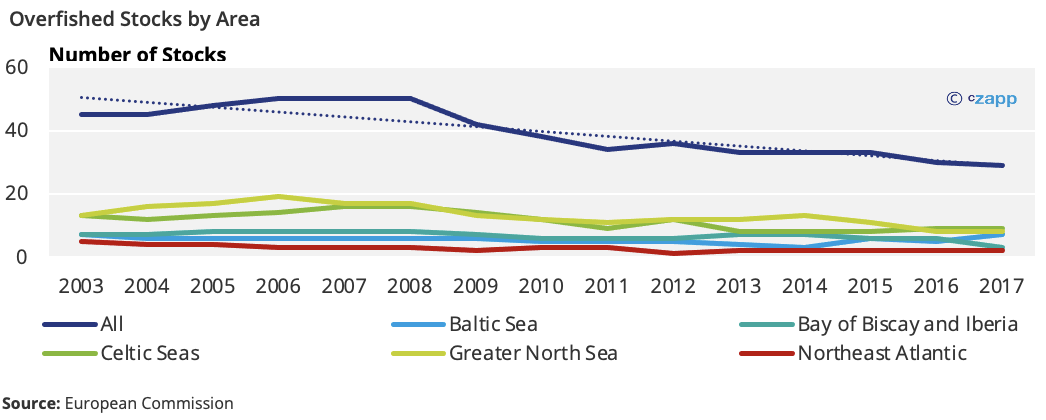

Through these tools, the EU has been making progress on overfishing. Since 2003, the number of overfished stocks across five seas fished by EU fishermen declined from 45 to 29 in 2017.

The Benefits of Sustainable Fishing

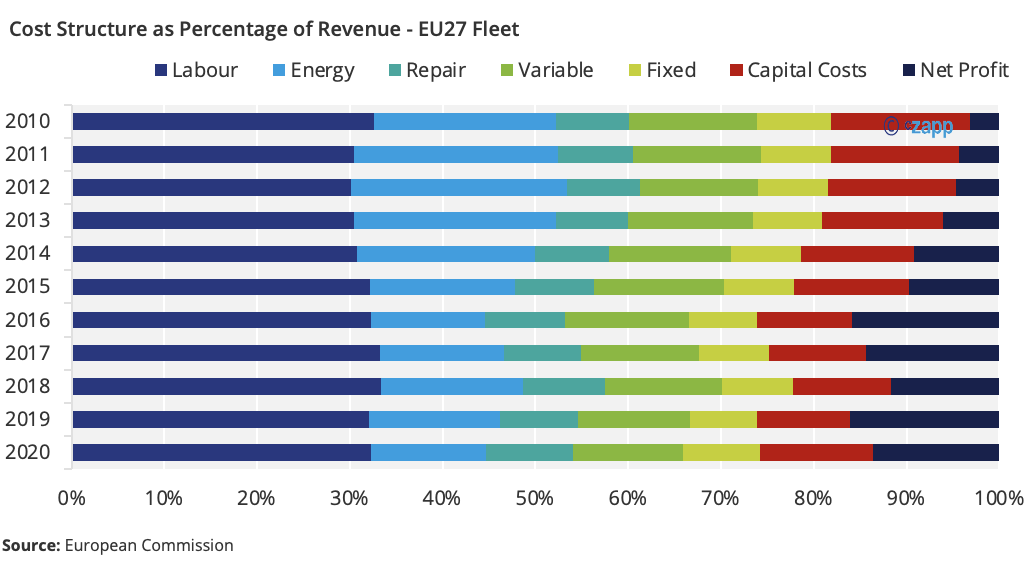

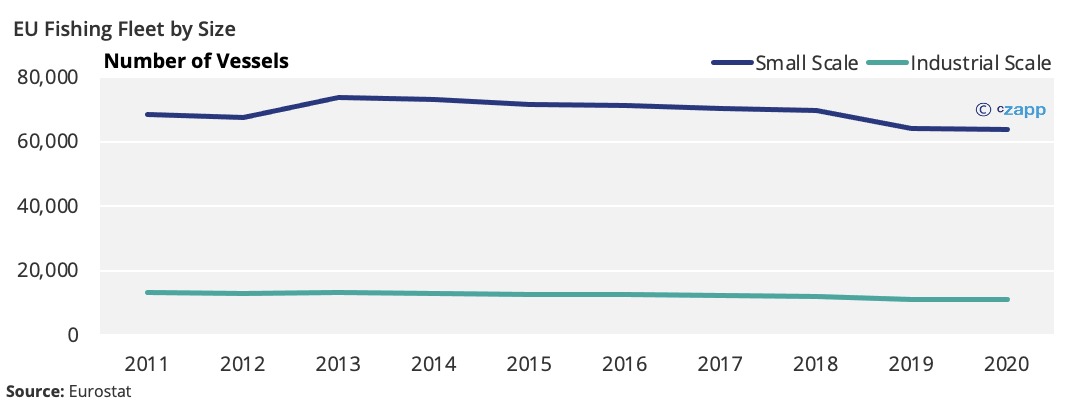

Although the EU fishing fleet is growing smaller, labour productivity is increasing, and fishing is ultimately becoming more profitable. Although energy costs have fluctuated in 2021, a decrease in variable costs and capital costs ultimately gave the industry more net profit in 2020 as a percentage of revenue.

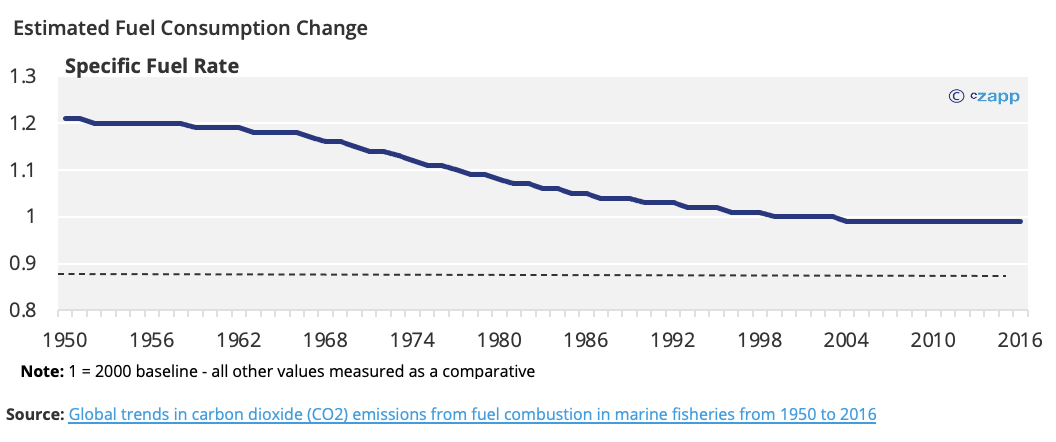

The industry is also becoming more fuel efficient, although this trend has been reversing since 2016 due to higher fuel prices. And although fuel costs as a proportion of revenue have been increasing since 2016, fuel intensity has declined to about 445 litres per landed tonne as of 2014.

Emissions intensity between industrial scale fishing and small-scale fishing has also converged dramatically. In 1950, emissions from the industrial sector were almost three times higher than the small-scale sector. However, a rise in small-scale operations, and new efficiencies in industrial fishing, mean the difference in emissions intensity is just 10%.

In the EU, a small-scale fishing vessel can be characterized as one that’s less than 12 metres long. According to Eurostat, there are almost six times as many small-scale fishing vessels in the EU as there are industrial vessels.

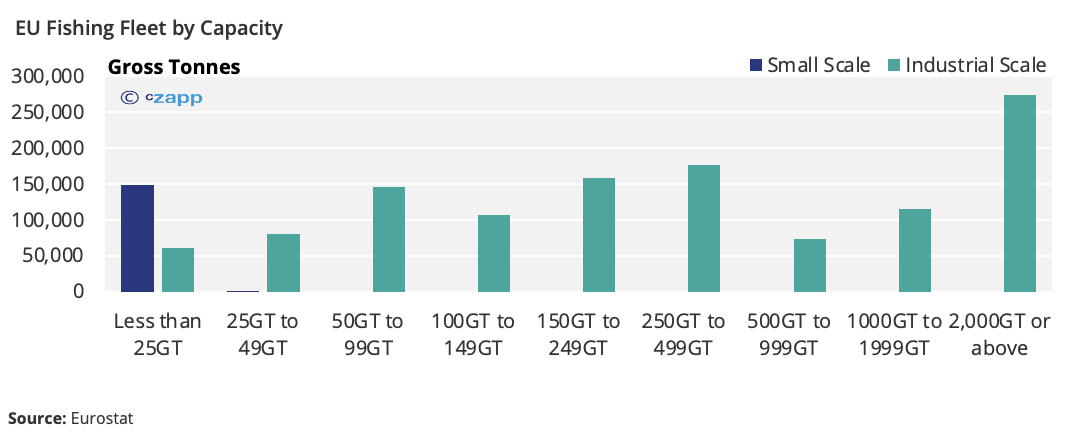

However, capacity on the industrial scale vessels is about eight times that of small-scale vessels.

Other Insights That May Be of Interest…

The EU’s Farm to Fork Strategy (At a Glance)