Insight Focus

Unfavorable weather conditions are impacting crops, with consequences for food security. The World Bank should make US$45 billion available to mitigate the problem, with part of the resources going to Latin America.

Food security worsens in Latin America

In Peru, the lack of rain in the Andean regions has impacted potato planting, one of the main foods consumed in the country. In Brazil, we again saw questions about the soybean harvest caused by unfavourable weather conditions. It’s not just an economy that suffers from this: climate change is becoming one of the main ingredients of food insecurity.

To minimize the problem, international organizations have been making resources available globally. After allocating US$30 billion in 2022 to combat food insecurity, the World Bank recently announced the availability of US$45 billion for 90 countries.

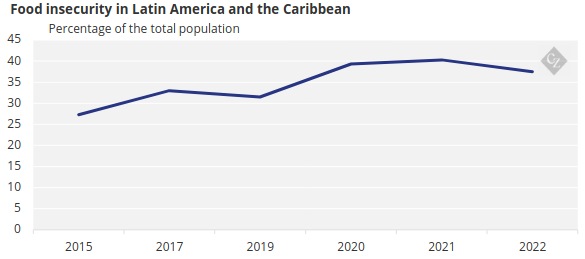

Latin America and the Caribbean, the second region in the world with the highest rates of food insecurity, is expected to absorb part of these resources. “The topic has become a government agenda, such is its importance”, says Diego Arias, Agriculture and Food manager at the World Bank in Latin America and the Caribbean. See the interview below.

Diego Arias, practice manager, Agriculture and Food, Latin America and the Caribbean at the World Bank. Source: publicity photo/World Bank.

How will the US$45 billion that the World Bank has made available to reduce food insecurity be used?

The issue of food security has become a government agenda. The World Bank works together with countries to finance operations in partnership with local governments. This value was based on the current portfolio and growing demand for food security interventions. It also signals to countries that the World Bank is interested in addressing these issues.

Source: World Bank.

Does this mean that there is this amount of resource available, but its use depends on partnerships made with country governments?

Correct. If we look at 2008 or 2010, when there was a food security crisis, the World Bank allocated around US$2 billion additional investments per year in food security, with a portfolio of US$23 billion dollars, well above the original estimates. This time, the allocation was US$45 billion, with US$22 billion in new loans allocated. But its use depends on the demand and interest of countries.

Why did the World Bank increase the volume of resources available?

The World Bank stopped responding to crises and started preventing them. There is an indicator called IPC (Integrated Food Security Phase Classification), which measures the level of food insecurity in countries. When the IPC is expected to increase by more than 5%, as is being observed, the volume of resources for crisis prevention automatically increases.

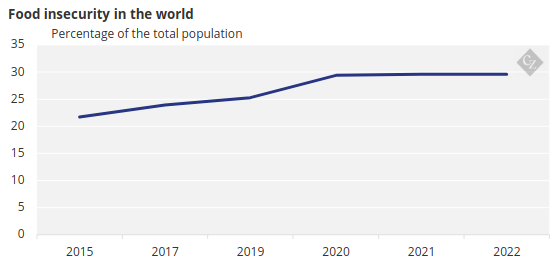

Over the past ten years, food insecurity has begun to rise, after declining for two or three decades. This reversal has worried countries.

And how much has food insecurity gotten worse in the last decade?

In Latin America and the Caribbean, it increased from 26%, on average, to 37.5% of the total affected population. In countries like Peru, today it reaches 50%. It’s too much. Now, Latin America is second only to Africa in terms of food insecurity.

Source: World Bank.

Why has food insecurity gotten so worse in the region?

There are several reasons. Some of the main ones are increases in the prices of food and inputs, mainly fertilizers and fuel. Another big reason is the impact of climate change on agriculture. That is why it is so important to invest in the sustainability and resilience of agricultural production models. But food security in the region is also affected by logistical deficiencies that cause market barriers for communities living in remote locations, for example. High production costs are another factor in this equation.

Brazil

Will part of the World Bank’s resources be directed to Brazil?

Yes. We are now processing the project portfolio. The programs focus mainly on family producers in the Northeast.

What are these projects like?

One of them is Bahia Que Alimenta, which will serve family farmers in the region. We will work with family producer cooperatives so that they can increase productivity. To do this, they need adequate financing. The idea is to create a business plan with family producer cooperatives so that they can present it to banks and obtain financing.

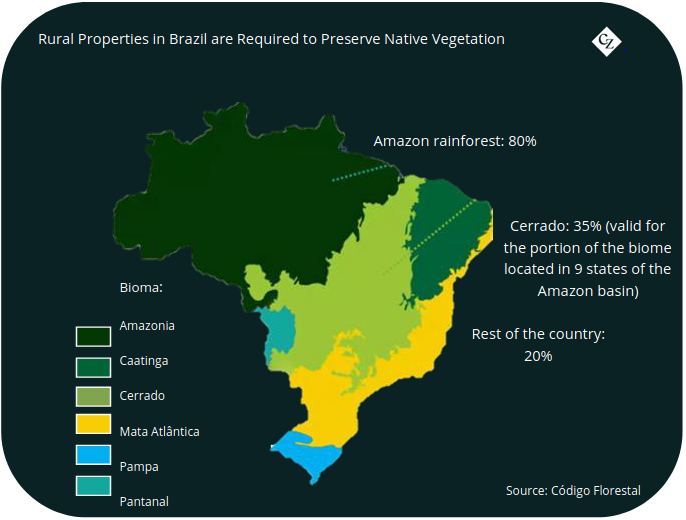

There are other activities that we are developing. One of the most important is to help rural producers and register with the Rural Environmental Registry, the CRA (editor’s note: by the end of 2023, all rural owners with properties with more than four tax modules, the size of which varies depending on the State, needed regularize; the deadline was extended until the end of 2025 for properties with less than four modules). It is an environmental regularization program that follows the Brazilian Forest Code. Brazilian farmers need to be registered with the CRA to access government support programs, such as subsidized credit. But some States have few regularized farmers. And without that, they can’t access any government programs.

How will the World Bank help farmers regularize?

The rural producer must fulfill a series of requirements and go in person to the state agriculture department for some procedures. It is also necessary to prove the existence of the Legal Reserve, the part of the land maintained with preserved forest, which needs to be at least 20% of the property, depending on where the farm is located. It’s a whole process and it’s not cheap for farmers who are far from the capitals. The World Bank’s role will be a mix of helping state governments improve the process and providing financing for rural producers to go through the necessary steps.

Tools like CRA should become increasingly important in a scenario of increasing demand for environmental preservation in food production, right?

Yes. An example is the European Food Import Law, which should restrict imports from areas with environmental problems. Other countries, such as China, may adopt similar measures. What Brazil is trying to do is embrace these new regulations, which could become a trend in the food trade, and establish standards and certifications to prove to the market that the products are sustainable.

Sustainability

The World Bank has been working on agricultural practices adapted to climate change in some countries in the region, such as Bolivia. What are these practices?

The concept of climate-smart agriculture is very well defined. The idea is to have agricultural technologies and practices that increase farmers’ productivity and profitability while enabling mitigation and adaptation to the impacts of climate change.

How is it possible to do this?

One of these techniques is the no-tillage system, which generates more profitability because the farmer uses fewer inputs and mitigates climate change because it reduces greenhouse gas emissions.

Another important technique is precision agriculture. There are tractors, for example, that apply very precise doses of fertilizers and pesticides. This reduces the number of inputs used, increases productivity, and emits less carbon.

But isn’t there an issue that precision agriculture is not affordable for most small farmers?

That is true. Studies show that farms with less than 200 hectares have more difficulty absorbing these technologies. But today there are startups working with family farmers to develop more accessible technologies for smaller-scale agriculture. There is potential for innovations accessible to small farmers.